Harold F. Pitcairn Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum, Willow Grove, PA.

It was September, 1974, and the carrier USS America was operating in the North Sea as part of a large NATO exercise. Fleet Logistics Squadron VR-24 in Naples, Italy had deployed two C-1As to support the America with Carrier Onboard Delivery (COD) of passengers, mail and cargo. On September 18th, the crew of one of the Grumman Traders, 146034, had departed from Flesland, Norway and was approaching the America on what was, so far, a routine flight to the ship. On board, they had four passengers, including an admiral, and several hundred pounds of precious mail. It was late in the afternoon and the ship was steaming in the Atlantic, northwest of Scotland. The sky was cloudy and gray and the water looked rough and cold. As they started a straight-in approach, the deck was pitching from the growing storm, and rain had started. About two miles out, the aircraft commander reached up to turn on the windshield wipers but got no response. At one mile out, all the pilot could see of the pitching deck and the visual landing system (the ‘ball’) was a blur of lights. He called for a go-around and the tower cleared the COD to enter downwind. The co-pilot had reset the wiper circuit breaker but they still wouldn’t work. Turning final, they were once again lined up poorly and had to go-around. The ship had the deck lights on full bright in the gloomy weather, but that was making it hard to see through the rain without wipers. To add to the problem, the C-1 was having radio issues. On the third approach, they finally communicated that they wanted the ship to lower the lights but the deck and ball were still somewhat blurry. The young aircraft commander knew he had to figure out this landing, as fuel was getting low and the rain was getting worse. He suddenly had an idea. As a version of the S-2 submarine hunter, the C-1 cockpit has side widows that bow out, so that crews can see downward to look for subs. He took off his helmet and stuck his head into the window. The eight or nine inches of window bow allowed him to see forward, and the curve of the window made the rain blow off. He could finally see the deck. Luckily, much of a carrier landing is accomplished by ‘feel’ rather than instruments, as he had no chance to look at airspeed or any other instrument as they came aboard. It wasn’t a pretty landing, and certainly wouldn’t be called ‘safe’ by modern standards, but it was what was done in the 1970s Navy, and the mission was accomplished.

That plane, C-1A BuNo 146034, is now part of the collection of the Willow Grove Wings of Freedom Museum and the landing was possibly this writer’s most difficult in a 50 year flying career.

The beginnings of the museum go back to just after WW-II. Lieutenant Commander David Ascher arrived at Naval Air Station (NAS) Willow Grove as the station’s first Aircraft Maintenance Officer. A local high school had a plane (a Curtiss P-40) that had been donated to them. Having no use for it, they contacted Ascher and he jumped at the opportunity to acquire the plane. Base personnel painted the P-40 and it was displayed at the fence along Rte 611. Getting a lot of positive feedback, Ascher then heard of a captured German seaplane that was at The Philadelphia Navy Yard. He arranged to have the plane, an Arado, transported to Willow Grove and, by 1947, there were two planes along the fence of the Air Station. Through the years, the small collection grew. In the 1960s I flew out of Willow Grove on a C-119 to a Civil Air Patrol summer camp and I remember being intrigued by the display of planes along the fence.

Willow Grove collection, March, 1969 Photo courtesy of DVHAA

By the early 1970s, the planes were starting to show signs of age and reservists from the base formed a group to help slow the deterioration. By 1985, the group had become well established in the community and started to think about building an actual museum. They adopted the name Delaware Valley Historical Aircraft Association (DVHAA) and, with community support, the group was able to erect a restoration hangar in 2000 and the Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum opened in 2004.

The history of the airport at Willow Grove goes back well before World War II and the museum really has a dual focus- aircraft associated with Willow Grove as well as the story of Harold Pitcairn.

Harold F. Pitcairn was a businessman and entrepreneur. He attended the Curtiss Flying School in Newport News, Virginia in 1916 and from there he had a long career in aviation. He founded Pitcairn Flying School and Passenger Service in 1924 which was the first company to receive a government airmail contract. He eventually sold the company and, by 1934, it had become Eastern Airlines.

Pitcairn was also interested in aircraft manufacturing and purchased land in Horsham Pa to build a field he called Pitcairn Field number 2 (Pitcairn Field number 1 had been in Bryn Athyn Pa, eight miles away). He started building mail planes that he called “Mailwings” and from 1927 to 1931, he built a number of versions at Pitcairn Field.

Fred Herr, a Docent at the Wings of Freedom Museum, was recently doing research, referencing the “MailWings” newsletters published by Pitcairn Aviation in the 1920s and sent this updated information- “One of your paragraphs implies/hints that Pitcairn Mailwings were built in Horsham. This is incorrect; they were all built in the factory at Pitcairn Field #1 in Bryn Athyn (approximately 8 miles away). In April, 1929 the newsletter announced that a new factory would be built at Horsham (Pitcairn Field #2) specifically for manufacturing of autogyros. I sympathize with your error; for years the whole museum staff has been telling visitors that the museum's Mailwing was built "just down the road" at what is now the Tinius Olsen factory. We're trying to get everyone re-informed”. Updated 6/26/2020

And Fred added this information on 11/29/2020

In 1929 the hangar/factory at Bryn Athyn burned to the ground, taking all the Mailwing tooling with it along with several completed but yet-to-be-delivered Mailwing 7s. That finished production of the Mailwing 7’s. The Mailwing 8 was thus a new design with new tooling and was produced in the new Autogiro plant in Horsham. The 8 is about 20% larger than the 7 (my rough guess) with twice the payload and a more powerful engine; had Bryn Athyn not burned down I wonder if the 8 would even have been developed.”

Thanks Fred! An interesting insight into how museums are constantly updating knowledge of their collections.

Pitcairn Field, 1929 and Willow Grove, 1979 Photos Courtesy of DVHAA

By 1928 Pitcairn became intrigued with the autogiro design of Spaniard Juan de la Cierva and he ordered a C.8W autogiro (the W is because he specified a Wright Whirlwind engine). In 1929, Pitcairn entered into a partnership with de la Cierva to build autogiros in the US. (Autogiro was de la Cierva’s patented name. Other craft are called autogyros).

Harold Pitcairn after being awarded the Collier Trophy in 1930 Photo courtesy of DVHAA

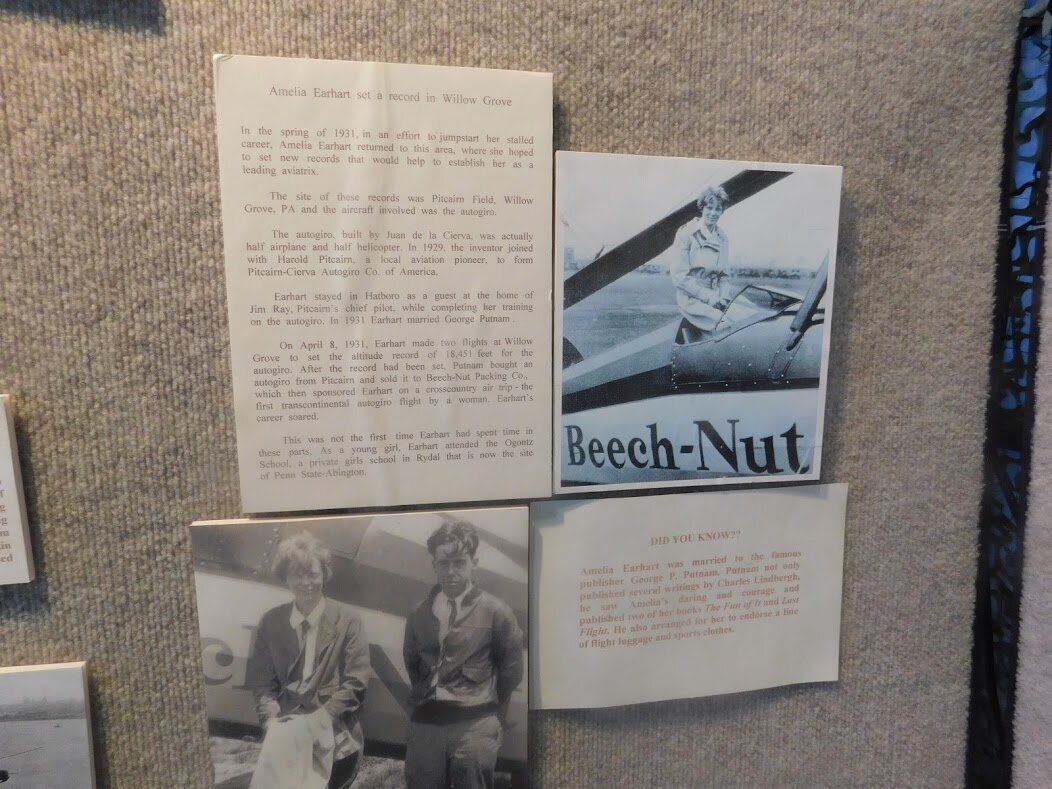

Although the Autogiro was never a commercial success, much of Pitcairn’s development work aided in the success of the helicopter. Both the US military and Igor Sikorsky used a number of his patents. By the early 1930s, Pitcairn and Willow Grove had become well known for the Autogiro activities. Amelia Earhart visited and became the first woman to solo an autogiro as well as setting an altitude record of more than 18,000 feet. Pitcairn continued developing the Autogiro at Pitcairn Field until 1942, when the Navy bought the property and changed the name to Naval Air Station Willow Grove.

The centerpiece of the Museum building is this beautifully restored 1931 Pitcairn PA-8 Super Mailwing.

The PA-8 was the largest and fastest plane built by Pitcairn. Mailwings had a reputation among pilots as being very well-built and good to fly and the PA-8 could carry 1,000 pounds of mail. A unique feature of this plane is a ‘zipper’ down the side that can be opened to access mechanical components. It had many owners over the years, but it wound up back in the hands of the Pitcairn family and, after it was restored in New Jersey, it was donated to the Willow Grove Museum in 2012. The museum is now named the Harold F. Pitcairn Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum.

Besides the Mailwing, the museum building contains a wide-ranging collection of displays, memorabilia and original items. It is jam-packed with interesting displays such as this huge flying model of a B-36, and many other high-quality aircraft models.

There are several full-sized aircraft in the museum building including this Lockheed P-80C (the Navy designation was TV-1). One of the oldest planes in the collection, this Shooting Star was built in 1948. It served at Willow Grove in the 1950s and remained after it was retired. The DVHAA did a beautiful restoration that was completed in 2005.

There are so many displays in the museum that you wind up making several laps around the floor and seeing something new each time. I especially enjoyed the display cases for different eras. These cases are not extensive, but they give a nice overview of the equipment and events of the time.

This restored R-1820 Wright Cyclone engine give a fascinating up-close look at the complexity of a WW-II era radial engine. The 1820 engine powered a number of aircraft including the B-17 as well as the C-1A and the UH-34D in the Wings of Freedom collection.

Outside of the museum building is a growing collection of almost 20 aircraft. Many of these planes were based at Willow Grove, in most cases, as their last assignment. One of the planes remaining from the early years of display along the fence is this rare Convair F2Y Sea Dart.

The Sea Dart was developed following WW-II as a supersonic fighter that would land beside a carrier rather than on it. At the time, supersonic jets were considered too fast to land on a carrier (the first Navy carrier jets were all sub-sonic). Despite the obvious operational difficulties, the Sea Dart performed well and is still the only seaplane ever to attain supersonic flight. By the mid-1950s, the problem of landing fast jets on a carrier was being solved and the F2Y was shelved after only five were built. One was lost in a mid-air break up and three of the remaining Sea Darts are on display in museums.

Another plane remaining from the collection that was displayed along the fence is this Vought F7U-3 Cutlass. Obviously suffering from many years in the open, the Cutlass sits at the restoration facility waiting for a full restoration. The tail-less Cutlass was an unusual design that had many teething problems. It was under-powered, had stability and mechanical issues, and eventually had a very short life as an operational carrier aircraft. The museum’s F-7U, BuNo 129642, built in 1954, likewise had a short operational life, as it logged just 326.3 hours. During its short career, it was attached to three different Navy squadrons in Oceana, Virginia. This plane came to Willow Grove to be part of an airshow in 1957 and, while here, the Navy decided to retire it. It was used for a while for ground training and it became part of the DVHAA collection in 1960. Of around 300 built, it is one of only four known to survive. (Thanks to reader John Benton, who sent a correction and additional information about this aircraft).

Many aviation museums have restoration facilities. A few are available for tours and Museum co-restoration chief, Nick Weremeychik was kind enough to show me around the hangar. On the day I visited, there were at least a dozen volunteers busy with the current project, an F-4A Phantom II.

The iconic, Mach 2.2, McDonnell-Douglas F-4 served for many years with the Air Force, Navy and Marines and this Vietnam-era fighter also served, and still does, with many other countries. The Willow Grove F-4 is an A model that was assigned to several research and test squadrons. As there were relatively few A models built, parts are not readily available. Volunteers have had to fabricate many parts to bring the Phantom back to its original look. It served in three squadrons in California and then spent some time at Griffiss AFB in upstate NY. It eventually wound up stored at Quonset Point Rhode Island, and was acquired by the DVHAA.

The F-4 will be painted in this original paint scheme and should join the collection by the summer of 2020.

Behind the restoration hangar is this P-3 Orion which was stationed at NAS Willow Grove and has been on display here for many years. The Lockheed P-3 was first introduced in 1964 as an anti-submarine hunter and it remains operational in that role today. This B model is just completing a refurbishing and will soon take its place again in the collection.

The McDonnell-Douglas A-4 Skyhawk served for decades with the Navy and Marines in numerous roles. Introduced in 1956, production continued until 1979 and the Skyhawk remained in service well into the 1990s. There were 2960 Skyhawks built, including over 500 TA-4J two-seaters. These A-4s served as the Navy’s advanced jet trainer for over 20 years. The A-4 was a relatively small and inexpensive, single seat, single engine fighter, but it could carry a bomb load equal to a B-17. The versatile jet served in many roles, including adversary trainers, and with the Blue Angles. They are still in service today with several foreign countries.

The A-4 in the museum, BuNo 158182, served with several Marine fighter squadrons and its final assignment, with Marine Attack Squadron 131, was at Willow Grove. This is another excellent example of a restoration by the DVHAA.

This Fairchild A-10 Warthog was assigned to Willow Grove in 1992 as part of the 111th Fighter Wing, PA Air National Guard. The A-10 is a very unique and special plane that is still a front-line fighter despite many efforts to retire it. My brother Mike (who is also my editor) flew the A-10 for many years and I asked him for his impressions:

“The A-10 could well be the winner of the award for an aircraft that met or exceeded its military requirements, builder’s promises, and pilots’ expectations. It was built to keep Soviet tanks from making it through the Fulda Gap in Germany at the start of WW III. Perhaps its mere presence made that unnecessary, and it went on to excel in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Bosnia. In addition to being an awesome weapon of war, it was an absolute pleasure to fly. In my opinion, Fairchild got everything right. I flew it for 2,000 hours, with only the most minor squawks. They have been talking about retiring it ever since 1983 when I first flew it, but it is still in the thick of battle today.

The most often heard criticism, its lack of speed, is due to the Air Force’s insistence that it be cheap (the engines are off-the-shelf items used on the Navy S-3 and the Canadair Regional Jet), and have an effective high-low-high combat radius greater than the F-4 and F-16. That was not a major problem as pure speed is not necessary for the A-10 mission. The “Hog” will carry 16,000 pounds worth of any weapon in the inventory, plus 1200 rounds of 30mm ammo for its 4,000-pound GAU-8 Gatling gun, stay airborne in combat for 3 hours, and can air refuel. The GAU-8 is an incredibly powerful gun (the recoil is greater than the thrust of one engine), extremely reliable, and will destroy anything the pilot is able to see.

The desert wars proved that it could, indeed, make it home with battle damage resembling a WWII B-17, as Fairchild had promised. It is now equipped with all the current “magic” electronics to work alongside the newest combat aircraft, far exceeding its original design goal as a day, good weather attack aircraft. It will go down in history as one of the great combat airplanes of all time”. Thanks Mike!

The Vought F8U-1 “Crusader” is a 1950s era jet fighter that served through Vietnam. The F-8 had a distinctive wing pivot of seven degrees which it used to increase the angle of attack for takeoff and landing.

F-8 with its wing in the takeoff/ landing position aboard the USS Hancock c1972 . Photo by Pete Sakaris, U.S. Navy.

The Crusader was flown by both the Navy and Marines and was a hot performer in its day. Its single Pratt and Whitney J-57 engine with afterburner powered it to many speed records. It was the first jet aircraft to exceed 1,000 MPH and, after takeoff, it could easily fly straight up. The museum’s F-8 entered service in 1957 in Alameda, California and completed its service at Willow Grove attached to a Marine Reserve squadron in the 1970s.

An interesting note about the two photos above. In the early 1970s, carrier aircraft had colorful squadron paint jobs, logos that identified the squadron and other distinctive markings, even the name of their carrier. The Navy decided that these paint jobs were giving way too much information to the Russians, and instituted a new policy that resulted in bland paint jobs, like the museum F-8. Today planes on a carrier all look the same. A colorful bit of history lost, but a necessary change.

Let’s return to the C-1A featured in the opening paragraph. After its tour in VR-24, 034 was assigned to VRC-40 in Norfolk. It also served as a ship’s COD on the USS Independence and in this capacity, it was based at Willow Grove. This C-1 was retired in 1987, after 30 years of active duty, and was immediately put on display next to one of the main gates. It was soon transferred to the museum and was given a restoration in the 1990s.

The C-1A was developed from the S-2 submarine hunter. It has the same Wright 1820 radial engines and basically the same systems and avionics. One upgrade in the cockpit was the addition of an Instrument Landing System (ILS) receiver, as a typical COD spent as much time at civilian airfields as it did at the ship. The fuselage was enlarged, allowing for nine seats (eight passengers and an aircrewman). These seats could be removed to add a cage for cargo hauling, with a 3500-pound capacity. Any combination of seats and cargo could be quickly installed (cage parts were carried in the nacelles), making it a very flexible transport.

The same C-1 (146034) on the ramp at Capodichino Airport, Naples, Italy, in September, 1974. Two aircraft and a maintenance crew ready to deploy to Scotland and Norway for two weeks, supporting a NATO exercise. (Author- top row, third from the right).

The C1 was interesting to operate at the carrier. With its straight wing and slow approach speed (92 kts), it had capabilities that jets didn’t have. In April 1974, for instance, after devastating floods in Tunisia, the Navy sent several ships, including the carrier Forrestal, to aid in relief. The fleet anchored off the coast for two months, and Navy helicopters flew numerous relief missions off the ships. Meanwhile, C-1s from VR-24 (including 034) landed on the carrier to re-supply the effort. The at-anchor landings (which jets couldn’t do) resulted in touch-down speeds 20-30 knots faster than normal (due to much less wind than when the carrier was underway). The landings gave a bigger jolt to the crews, but were well within the capabilities of the C-1.

Photo Courtesy of DVHAA

The Harold F. Pitcairn Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum is an incredible museum, staffed by dedicated people who do great work and are always available to answer questions and add interest to your tour. This is another of those lesser-known museums that is truly a great place to visit.

______________________________________________________

I would like to thank Nick Weremeychik, museum co-restoration chief and Virginia Brooke, museum historian, as well as others of the museum who provided assistance and information. A special mention of museum volunteer Dave Brown, who also flew C-1, 146034 (at VRC-40 in Norfolk).

Thanks also to my brother, Mike, for continuing assistance and my son Mark and his wife, Taylor, who helped me get started on this project and who are always ready to provide technical assistance. And to my wife, Sheri, and the rest of my family who are always available for advice.

_______________________________________________________

To learn about what to do in the local area, museum hours and costs as well as books to read and other interesting odds and ends, keep reading! At the end you will find a photo gallery of the entire museum.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

The museum is open Wednesday through Friday, 10:30-3 and 10:30-4 on weekends. Admission is $8 for adults, $6 for seniors and vets, $4 for children 6-18, and free for active duty military. Group admissions are available as are annual and lifetime memberships.

FLYING IN

Even when the Air Station (KNXX) was open, you would not have been able to fly in. There are a few choices, but none extremely convenient.

KLOM Wings Field is 10 miles and 20-30 minutes away. It has a 3700’ paved runway and RNAV approaches. It has typical services available but contact the airport for overnight parking and rental car availability. Wings was opened in 1937 and has quite a bit of aviation history itself. Unfortunately, Wings does not have a museum, but the FBO has a number of historic photos on the walls.

KDYL Doylestown Airport is 14 miles and 20-30 minutes away. It has a 3000’ paved runway and RNAV and VOR approaches.

KTTN Trenton NJ, Mercer County Airport is 26 miles and about 35 minutes away. If you need a longer runway (6000’), hangar, or other services, Trenton is a good option.

LOCAL ATTRACTIONS

Center City Philadelphia, with all its history, lodging and dining is about 45 minutes away. For a tourist location, try New Hope Pa. Located about 30 minutes away, on the Delaware River- a beautiful old town with restaurants, antiques, a theater and train rides. For younger children, Sesame Place is also 30 minutes away.

WHERE TO EAT

Lancers Diner, near the south end of the base on Route 611, is a traditional small-town diner, open 24/7. There are many other restaurants nearby, from fast-food to fine dining.

If you want the best cheesesteak in Philly (my opinion)- it’s just 30 minutes to Dalessandro’s in Roxborough (600 Wendover St, Philadelphia, Pa 19128).

SUGGESTED READING

My daughter-in-law, Angela, recently recommended The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah. It is an excellent novel about the French resistance during WW-II. There is not a lot of flying in the book, other than it revolves around two sisters who risk their lives to help downed Allied fliers escape from occupied France. It is an excellent read.

A friend of mine, Bill Harlow, is a retired Navy captain and former chief of public affairs for the CIA. He is also an author and one of his books, Circle William, centers around Naval operations in the Mediterranean. The intricate Clancy-style novel is fast paced and an interesting read. Written in 1997, it can be found at a very reasonable price on the usual sites.

MUSEUM WEBSITE

https://wingsoffreedommuseum.org/wp/

UP NEXT

Military Aviation Museum of Virginia, Virginia Beach.

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

I recently attended the dedication of a C-1 that was added to the display that sits in front of the Defense Supply Center in Northeast Philadelphia. The center now has seven aircraft on display out front. The newest, C-1 Bureau #136792, is unique in that it has twin vertical stabilizers, rather than the usual single stabilizer (as in 034, above). This C-1 was used as a test bed for the development of the E-1 aircraft (which has a radar dome). It then entered into service as a standard C-1A Carrier Onboard Delivery aircraft.

C-1 pilot Jim Woodall gave an excellent talk about flying the COD at the dedication. Scroll below the photo gallery to read it. You will enjoy it.

I was reluctant to include this display, for obvious reasons. However, it does fit the category, and it is in downtown Philadelphia, so it fits this issue. Located on Cherry Street, just off Broad Street, the former S-2E Tracker by artist Jordan Griska is titled Grumman Greenhouse. Greenhouse refers to plants that are supposedly growing inside the plane as a benefit to the community (you can see the glass on the bottom of the fuselage). I’ll let you form your own opinion of this ‘work of art!

Update- 8/9/22. This work was originally intended to be temporary and as of 8/15/22 it will be removed from Lenfest Plaza in Philly, where it has been on display for 10 years. Anyone have an idea for a new home?

PHOTO GALLERY

photos are clickable

Issue 10, Copyright©2020, all rights reserved. Except where noted, all photos by the author

______________________________________________________

Keynote speech from the C-1A dedication at the NAVSUP Weapon Systems Support’s static display C-1A, September 19, 2019, Philadelphia, Pa. Jim Woodall, C-1A pilot

“I have a picture on my bookcase. It's a black and white photo of me bringing a C-1 aboard the USS America during my first summer in the Mediterranean. At various times while growing up my kids would ask, "Dad, was that your plane?" Followed usually by "Was it from WWII?" Well, very nearly.

I flew the C-1 from 1979-1981 in Fleet Logistics Support Squadron 24, or VR-24. It's a museum piece now, but I assure you to those of us that flew it, it seemed like one even back then. Most pilots like to brag about the plane they fly being the first in something: the first to exceed a certain speed, the first to attain a certain altitude, and so on. The C-1, however, was a plane of lasts, and we who flew it were very proud of that.

The C-1 was the last piston engine driven aircraft in the Navy, burning 145 octane aviation gasoline instead of kerosine-based jet fuel. I'll have more about these engines later. It was the last non-pressurized, non-oxygen carrying, non-air conditioned aircraft in the Navy. This probably doesn't mean much to you, but to us it meant it was hot as hell in the summer and cold as a wedge in the winter. The C-1 was the last shipboard aircraft without ejection seats, requiring us to bailout way back at the boarding door. Technically, the A-3 Skywarrior didn't have ejection seats either, but those guys had an escape slide right behind the cockpit, and we considered that cheating. Per regulation, we didn't wear parachutes while carrying passengers; I guess the Navy considered it poor form to abandon ship while passengers were still strapped into their seats. I disagreed with this policy, however, as I figured there was only a finite number of pilots, but a virtually unlimited supply of passengers.

The C-1 was the last aircraft to perform free deck launches. I think we've all seen old WWII footage of the planes trundling across the deck, dropping off the edge and slowly rising back up. Well, that was us. It was a pretty tense operation since we rarely attained more than 65 knots by the end of the flight deck, which was barely above stall speed and about 20 knots below minimum control speed single engine. Which meant that if you lost an engine during this maneuver, your best bet would be to chop power on the good engine and get ready to go for a swim. We naturally preferred catapult shots, which added a good 40 knots to our end speed and usually much more since we normally lied to the catapult operator about our weight. After all, as all pilots know, "Speed is Life."

The C-1 was the last aircraft to take a cut. More modern aircraft, jets and turboprops, follow the visual glideslope, or ball, until the Landing Signal Officer, the LSO, judges them close enough to the landing area, then activates the green lights on the fresnel lens to signal the pilot to advance the throttles to max power. This gives the turbines a few moments to spool up in case of the hook not catching a wire, or bolter. This is why footage of arrested landings shows aircraft straining forward after a trap. In contrast, piston powered aircraft have instantaneous power, as anyone who's stomped on the gas pedal of a high-performance muscle car knows. When we saw the green lights we'd immediately chop power and fall out of the sky in a somewhat controlled crash, hence "the cut." Experienced LSO's could cut you for a particular wire.

Getting back to the engines, they were certainly powerful: supercharged, 9 cylinder brutes displacing 1820 cu. in. (or nearly 30 liters) and generating 1525 horsepower each. This was a problem all its own when you were flying single engine; all that power out on the wing tended to turn the airplane 90 degrees and try to make it fly sideways, which doesn't usually work unless you're in a helicopter. Keeping the aircraft in balanced flight while single engine was the greatest challenge in flying the C-1. And that's where this airplane really taught me how to fly. Because make no mistake, when I arrived at VR-24 as a young Lt(jg) with barely 800 hours of flight time I was dangerous. And I don't mean the good kind of dangerous, the Maverick-Top Gun kind of dangerous. No, looking back on it now, I'm surprised I could take an airplane up and bring it back down without either substantial airframe damage or a flight violation. But wrestling with that beast around the landing pattern a few hundred times with a simulated single engine really honed my stick and rudder skills to a new level.

We flew the C-1 with a crew of three: aircraft commander, copilot and an enlisted aircrewman, called a plane captain, who was a combination loadmaster, mechanic, ticket agent, and flight attendant. Because we were really the 6th Fleet's little airline, hopping all around the Mediterranean theater taking mail, high priority cargo, passengers and VIP's to the ship and any port smaller ships might have ventured into. We could hold 4000# of cargo/mail or 8 passengers in seats that folded down from the side of the fuselage and in military fashion faced aft. VR-24 was a unique squadron; at the time it was the only one in the Navy with jets, props and helos. We had pilots who had flown every conceivable type of Vietnam-era aircraft: F-8 Crusaders, A-7's, F-4's, Cobra gunships, even AD Skyraiders. And S-2 Trackers, of course. That mix made for some very interesting happy hours.

The way Grumman constructed the C-1 you'd swear it was made out of cast iron and its ruggedness saved my life on several occasions. I'll tell you about two of them.

We were flying from Sigonella to Naples, the way most of our missions started out. We were in complete instrument conditions at 10,000'; thunderstorm activity had been reported in the Naples area. And that was the glaring deficiency in the C-1's avionics array: no weather radar. Now I don't know why that was. Either the Navy didn't want to spend the money, or more likely, weather radar hadn't been invented yet when the C-1 came off the assembly line. Either way, we totally relied on the ground controller to inform us of weather buildups and vector us around them while in instrument conditions. As luck would have it, Naples' radar had been knocked out by a lightning strike, so they were blind as well.

Now, for some reason, I had decided this was a good time for the enlisted aircrewman to come up and get some stick time, so he and the copilot had exchanged places. Honestly, sometimes I wonder about my judgement in those days. Well, it got bumpier and bumpier the closer we got to Naples and I finally told them to get back in their proper seats. The copilot hadn't yet finished stepping back into his seat when we penetrated the wall of a thunderstorm at 10,000'. Now, if you were conducting scientific research on convective activity, say, as a hurricane hunter, and you wanted to find the exact worst altitude for extreme turbulence, well, you'd pick 10,000'.

I can't really describe that ride, except it was like when I was once in a car crash but happening over and over. The first jolt slammed the copilot into the overhead and then back down into his seat, and I never saw anyone strap back into his harness so fast in my life. The cockpit door was torn off its hinges and tumbled to the back of the plane. The altimeter was spinning up 3000' and back down 3000'. The VSI was pegging out at the top, then pegging out at the bottom. We couldn't even get a radio call out; we were just hanging on for dear life and trying to keep the right side up. After more of this fun than I ever want to have again, we suddenly popped out the other side and into clear air, none the worse for wear except for both engines' fire warning lights coming on due to the amount of water pouring through the nacelles and shorting out the wiring. I'm convinced no other airplane, at least none that I've ever flown, could have held together through this.

One last story will show just what a flying tank the C-1 was. We were going from Marseilles, France to Hyeres, a French air base right across the bay, about 15-20 minutes away. We had two aircraft commanders paired up, which is usually a mistake, and to make matters worse, Jay was the outgoing NATOPS Officer, the chief instructor and check pilot for the squadron, and I was the incoming one. A recipe for disaster if I ever saw one. It was early morning and as we taxied out we saw a lineup of 25-30 airliners all awaiting clearances. So we decided to pull an old trick we used at places we frequented all the time: Naples, Rome, Athens. We would cancel our IFR clearance, move to the head of the line, take off VFR, and when airborne call up an enroute frequency and refile inflight. Easy. Well, this is what we did and after takeoff, Marseilles Tower turned us to a southerly heading, told us to maintain 1,000' and report "Pt. Vou la frou fou." I don't know, it's 40 years later and I still don't know the name of that point. Well, unbeknownst to us, there were local visual course rules in Marseilles which stipulated a turn after takeoff to a heading of 180, climb to 1000' and reporting that visual reporting point. Also unbeknownst to us, there was a series of ridges just to the south of Marseilles between the airport and the sea. So I'm holding onto that heading and 1000' while Jay was trying to identify the point and get us released. Now, if there's one thing we know about the French it's how completely forgiving they are of foreigners and their language difficulties. So naturally, now they stopped talking to us.

So I'm flying the airplane and Jay now has the instrument chart out all over the cockpit in a vain attempt to find that point. I now see a cloud bank coming up ahead and tell Jay to ask for a climb. And Marseilles comes back with, "Negative, JM412, departure traffic overhead, maintain 1000' and report Pt. Vou la frou fou." Jay was arguing back and forth with the controller while we plunged into the clouds. We weren't in it very long when I started noticing little flashes of color out of the corner of my eye, but every time I turned my head to look out the side window it was solid white again. This hadn't gone on very long when the plane captain yelled over the ICS "We're in the trees!" Then it suddenly dawned on me what those little flashes of green and brown had been. I firewalled the props and throttles and yanked back on the yoke and we burst out of the ground fog, which is what it was, and into clear blue sky. Then I turned to Jay and yelled, "Just tell 'em we're over that f---ing point!!" So he did, not in those exact words, and Marseilles Tower comes back with, "Roger, JM412, au revoir." And we looked at each other, like that's all it took? Just SAYING we were over the point? Well, I learned an important lesson that day about air traffic control: when all else fails, just lie your ass off.

We proceeded to Hyeres with our pulses pounding and our heads spinning and our knees knocking, as anyone who's almost become a smoking hole in the ground would recognize. My legs were shaking so bad that after landing I could hardly bring the aircraft to a complete stop and set the parking brake. We were still shutting down the engines when the plane captain dived out of the airplane and we hadn't yet finished the checklist when he was back up in the cockpit saying, "You guys have got to see this." So we followed him out and looked at the airplane.

As you can see from the aircraft behind me, the paint scheme at that time was glossy gray on the top and glossy white on the bottom. OUR aircraft was glossy gray on the top...and bright green on the bottom. There were leaves and twigs and even tree bark stuck in every nook and cranny on that airplane. The outside air temperature probe that stuck out of the bottom of the fuselage was bent back at a 45 degree angle.

Well, we recognized at once that this was a very serious situation, one that called for an immediate response. And, like all good, red-blooded naval aviators, we decided to do the right thing:

We bent that air temperature probe back to a semblance of a perpendicular position; we picked every bit of leaves and twigs and vegetable matter out of wherever it was lodged; and the plane captain spent the next hour on his back polishing all the grass stains off the belly of the aircraft.

AND.WE.NEVER.TOLD.A SOUL.

Now, Admiral, that was in 1980. And I'm really hoping the statute of limitations has run out by now.

My kids have asked me from time to time what my favorite airplane was. And out of five different naval aircraft and eight civilian airliners, well, you're looking at it. The plane that taught me how to fly, the plane that saved my life, the plane I grew to love. The C-1A Trader. Thank you”.

Thanks Jim!