Wright Brothers National Memorial Part 2

Issue 7 A tour of the grounds of the Memorial

The morning of December 17th, 1903 was cold and damp on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. There had been a storm the night before and puddles from the rain were iced over. The wind was about 25 MPH which was higher than the Wright Brothers would have liked for their flight. They waited for it to die down, but eventually decided to attempt to fly anyway. They laid down their launch track directly into the wind and raised a flag to signal to the men at the Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station that they were ready to fly. They went back and forth to their cabin continuously to try to keep warm. Three members of the Life-Saving Station soon arrived to help, as well as a local businessman and a teenage boy, and all was ready for their attempt to fly. Orville later wrote that the strong winds concerned them but after years of calculations and experimentation they were convinced that their machine would fly. They had made an attempt on December 14th, but only flew a few feet before crashing. It took a couple of days to make repairs and they were ready to try again. Wilbur had won the coin toss to fly first on the 14th and so now it was Orville’s turn. The rest, as they say, is history.

Note- this blog is part 2 of the tour of The Wright Brothers Memorial- click here for part 1

https://aviationhistorymuseums.com/blog/2019/10/28/wright-brothers-national-memorial

After leaving the Wright Memorial Visitor’s Center it is a short walk to the site of the first flight. You first come to replicas of the cabin and hangar that the Wrights had built by 1903. Their first year at Kill Devil Hill (1901) had been pretty miserable. At first they only had a tent for shelter and they endured mosquito swarms, a hurricane, lack of supplies and even attacks by wild boars, but the two were so determined to fly that they took the hardships of Kitty Hawk in stride. At the end of 1901 they built a wooden shed and, by 1903, they had two wooden structures that were well stocked with tools and supplies.

The building on the left was a hangar and the one on the right was living quarters and workshop. The replicas are very accurate, including the interior of the living quarters, designed from original photos of the cabins.

You next walk over to the markers that represent the takeoff point and the four landing points of the December 17th flights. It is a pretty interesting feeling to be standing on the exact spot where the first powered flights took place. I asked one of the Park Rangers how accurate the locations of the markers are. He said that historians are pretty confident that they are all within about a foot of the original locations. The Wrights made many notes and took pictures and, while the buildings are long gone, parts of the foundations that the brothers built are still there. In addition, at the 25th anniversary celebration in 1928, all the people who were present in 1903 attended (except Wilbur, who passed away in 1912). They were all interviewed about their memories and there was general agreement about the locations.

The original photo of the first flight shown above was really pure luck. As the locals arrived to observe and assist, Orville and Wilbur were busy with final adjustments to the Flyer. Wilbur had placed his camera on a tripod and aimed it in the general direction where he thought the Flyer would be airborne. He told John Daniels how to release the shutter and asked him to take a picture if something happened. Daniels had never used the camera before and he almost forgot to push the shutter in the excitement of seeing the lift off. No one knew for sure if there was a photo on the plate or if the plane was even in the picture until a week later, in Dayton, when the picture was developed. What we have, of course, is a near perfect record of the first seconds of flight, including Wilbur alongside, having just let go of the wing. You can even see the elevator in front in the full up position.

The first flight lasted just 12 seconds and covered 120 feet. After carrying the Flyer back to the starting track and returning to the shed to warm up a bit, they were ready to go again. With Wilbur at the controls, the second flight was similar to the first, covering 175 feet. Because the wind had died down a little, Wilbur covered more distance in about the same time.

Returning again to the starting point, Orville got ready for his second flight. This flight covered 200 feet and was rather steadier than the first two. Orville had the Flyer well under control until a gust of wind dipped the left wing. In his first attempt to control the plane laterally, Orville was surprised at how effective their wing-warping system was. He overcontrolled a little and the right wing clipped the ground. The plane came to a sudden stop, but the Flyer was not damaged. This third attempt lasted 15 seconds.

It was around noon when Wilbur climbed aboard for the fourth flight. The first 300 feet of his flight went much like the first three; he was cycling up and down between 10 and 30 feet altitude. After the first 300 feet, though, he got it under control and the next 500 feet were smooth and level at about 20 feet high. Another gust then started the craft pitching up and down again. At 832 feet it struck the ground heavily. This fourth flight lasted 59 seconds. What doesn’t get mentioned much about the third and fourth flights is that not only had the Wright Brothers proven that their plane could sustain powered flight, but they had essentially taught themselves how to fly. They both demonstrated that they understood how the airplane controls worked and that they could pilot the machine.

The final hard landing had damaged the front rudder frame, but the main structure was undamaged. The Wrights figured it would take a couple of days to make repairs and then they would make some more flights. They were disappointed in the damage because, after the successes of the third and fourth flights, they felt that they could next have flown the four miles to Kitty Hawk, which would have used up the half gallon of fuel that their tank contained.

As the team picked up the Flyer to carry it back to the hangar, a strong wind gust lifted it and turned it over and over. Everyone tried to grab a wing, but it was of no use, the plane was badly damaged. There would be no more flights in 1903.

In fact, Wright Flyer Number 1 never flew again. The Brothers shipped it back to Dayton and stored it in boxes and, by 1910, they were ready to just burn it. Luckily, they were instead talked into exhibiting the craft at various places, including MIT. It was almost lost in the Dayton floods of 1913. Orville again considered what to do with their historic craft and he felt the obvious place where the Flyer should be exhibited was the Smithsonian Institute. Unfortunately, due to various patent fights and disputes over who really flew first, an agreement couldn’t be reached with the museum. The main sticking point was that the Smithsonian still refused to recognize the Flyer as the first to accomplish powered flight. Charles Walcott, the secretary after Samuel Pierpont Langley, continued to hold that Langley’s Aerodrome was the first to be “capable of flight” (this is a long and interesting story- told in most of the books about the Wright Brothers). The Flyer continued to be displayed in various places until 1928, when Orville made arrangements to have it shipped to The British Museum in London. By 1942, The Smithsonian had finally agreed to recognize that the Wright Flyer number 1 was the first to fly and negotiations (obviously hindered by WW-II) were underway to return the craft to the US. On December 17th, 1948, Wright Flyer Number 1 was finally put on display in the Smithsonian, where it remains today.

The Monument viewed from the 1903 takeoff point

Overlooking the site of the first flights is the 60-foot-high granite Memorial to the Wright Brothers. It is built on top of Kill Devil Hill that the Wright Brothers used for gliding experiments. The history of the Park and the Monument is a little confusing and I have heard and read differing accounts. I asked Mike Barber, the Park’s public affairs officer, about the timeline. He told me that the history can be confusing because people tend to use the word memorial to describe both the monument and the park. President Calvin Coolidge, on March 2, 1927, signed the Act authorizing the "Kill Devil Hills National Monument." Five years later, in 1932, the monument was finished and dedicated. In 1933, the monument and the park land were transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service. In 1953, Congress renamed and designated the monument as the Wright Brothers National Memorial. Wright Brothers National Memorial is considered the entire park, including the monument, visitor center, airstrip, etc.

Site of the first flights and the Visitor’s Center viewed from the Monument

It is a pleasant walk from the Visitor Center to the top of the dune. You can drive over to the area, although the only way to get up to the top is to walk. The Monument is hollow inside and contains stairs to the top. Originally planned to be open to the public, the small lobby area is only open occasionally (usually on a summer weekend). You cannot climb to the top any more, but the area around the Monument still gives you an excellent view of the Atlantic Ocean to the east and the Albemarle Sound to the west.

To get a feel for how this area looked to the Wright Brothers in 1903, you have to imagine that you mainly see sand in all directions. The area was forested in the early 19th Century but by mid-century,most of the trees in the area had been cut for ship building. The trees you see today were planted in the 1900’s. The Brothers would have been able to see Kitty Hawk to the north from Kill Devil Hill, slightly obstructed by the sand dune that they flew from in 1900. That dune did not exist until 1899, when it was formed by the San Ciriaco hurricane, still considered to be the most powerful known hurricane to ever hit the Outer Banks. The barrier islands that are the Outer Banks are ever changing, but the ground cover that has been planted here in the park has stabilized this historic site and will preserve it for years to come.

On the south side of Kill Devil Hill, is a sculpture of the first flight by artist Stephen A. Smith. Sculpted for the 100th anniversary in 2003, it is a life-sized replica of the moment of lift off. The Flyer is in stainless steel and the seven figures are bronze. The tableau is set exactly how each person was standing that day in 1903. If you visit at a quiet time, you can place yourself exactly where each person stood and get a feel for what they saw. If the park is busy, you can watch children climb up on the wing, pretending they are flying, and, even if by accident, experiencing history.

Just to the other side of the sand dune is the south end of the First Flight landing strip (KFFA). Next to the strip is a shaded picnic grove as well as restrooms and a flight planning room. No matter where you are in the park, you will see planes landing at First Flight or just overflying the Memorial.

The Berlin Airlift “Candy Bomber” DC-4 doing a fly-by

The Wright Brothers Memorial is a must visit for any pilot, but as a beautiful National Park and an incredible historic location, it is a great location for all to see.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

The memorial is open 9-5 daily except December 25th. The entrance fee is $10 (age 16 and older) and is good for 7 days. Children are free. You can buy an annual pass for $35 and, as The Memorial is a National Park, the various passes available for National Parks are good here.

FLYING IN

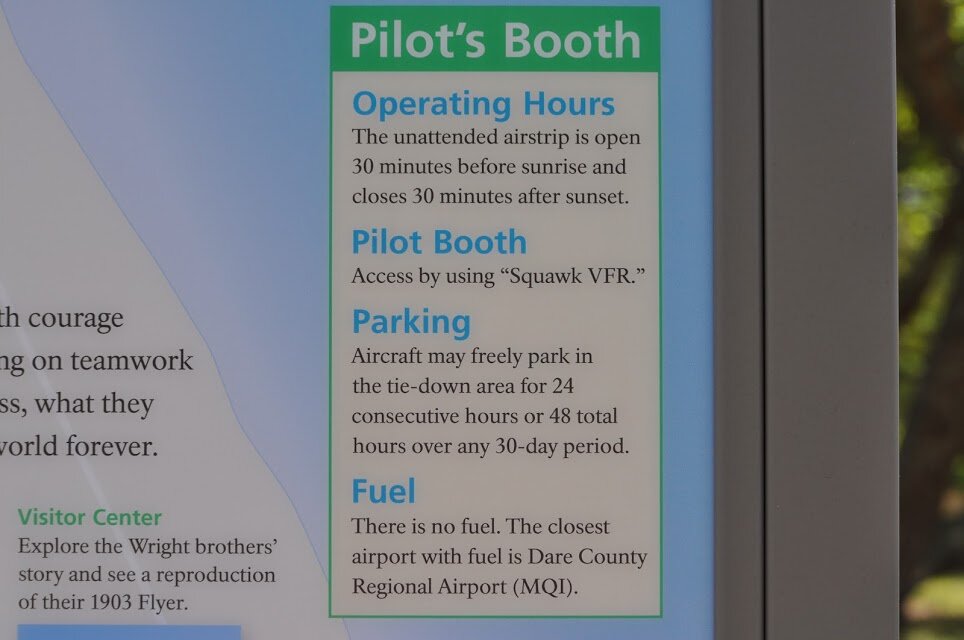

KFFA. First Flight Airport, opened in 1963, is a 3000’ paved strip adjacent to the Memorial. There are no services and parking is limited to 24 hours. There is a small, unattended, flight planning room, restrooms and a picnic area. It is a short walk to the memorial, and a very cool place to land!

KMQI. Dare County Regional is a full-service regional airport that is 6 miles away (a 20-minute drive but it can be much longer on summer weekends). It has 4300’ and 3300’ runways and RNAV, VOR and NDB approaches. The airport itself is historic, being built as a WW-II Coastal Command base. There is even a small, but interesting, museum in the main terminal (see issue 1- “Museums are Where You Find Them”).

LOCAL ATTRACTIONS

One recommendation I have when visiting the Outer Banks is to make a trip to Roanoke Island. There are many places to visit there including the Aquarium, Island Farm, Elizabethan Gardens, Festival Park, the fishing village of Wanchese and the old town of Manteo.

WHERE TO EAT

Previously, I mentioned two favorite restaurants near the Memorial. If you head down to Roanoke Island (about 20 minutes from the Wright Memorial), you will pass a couple more favorites. Basnight’s Lone Cedar Café and The Blue Water Grill and Raw Bar each have great seafood and great views. The Blue Water Grill is at Pirate’s Cove where many of the deep-sea fishing boats dock. If you are there in the late afternoon you can watch the boats coming in and unloading their catches.

SUGGESTED READING

In the last issue, I mentioned some of my favorite books about the Wright Brothers, and there is one more that should be mentioned. The Wright Brothers by Fred Kelly (1943) was the only authorized biography of the Wright Brothers. It is also very much worth reading. Last Christmas, my son gave me The Forgotten 500 by Gregory A. Freeman. It is the story of the rescue of the many flyers who were shot down over occupied Yugoslavia during WW-II. A covert operation by the OSS (a forerunner of the CIA), the story remained classified until recent years. A very intriguing and interesting read.

MUSEUM WEBSITE

https://www.nps.gov/wrbr/index.htm

UP NEXT

The Boeing Center- at the National WW-II Museum, New Orleans. LA.

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

A few years ago I was sitting at the gate in Santo Domingo and I noticed what looked like a graveyard of old planes off to the side, in a grassy area. The sight was very intriguing. I asked our mechanic about the area and he said they were planes that had been damaged beyond repair in various hurricanes. As we had several hours before our departure, I asked if we could get a closer look. We hopped in his little Jeep and set off across the ramp. We found quite a collection of old planes- they really should make it a museum! We were offered to go inside the planes but were also told there were a lot of snakes around. So- outside was fine! I have read that some of these planes have since been removed for restoration, but looking on Google Maps, there are still a lot there. Clearly some of the planes have been robbed for parts. If you are at the airline ramp, look to the south, on the other side of the corporate ramp. If you happen to fly in, you should be able to taxi quite near the area. There appears to be a dirt road that goes past the planes, but it’s hard to tell if it’s accessible to the public. Please excuse the photos- copied off my old prints!

Lockheed Constellation

Boeing 707

Convair 440

Boeing 727

Douglas DC-6

Curtiss C-46

PHOTO GALLERY

WRIGHT BROTHERS NATIONAL MEMORIAL

Click any photo to enlarge

Issue 7, Copyright 2019, all rights reserved. All photos by the author