The Museum Of Flight, Seattle Washington

In 1929, newspaper publisher Harry D. Strunk, of the McCook Daily Gazette, purchased a new Curtiss Robin C-1 for $8,000. His goal was to increase the circulation of his newspaper throughout Southwest Nebraska and Northwest Kansas. He modified the Robin with a 10-inch hole in the bottom and a metal chute through it. Six days a week, his pilots would fly “Newsboy” along a three-hour route, dropping bundles of newspapers over more than 40 towns to waiting paper carriers. The newspaper circulation increased over the next year, but the service came to an abrupt halt when the plane was heavily damaged by a tornado while sitting on the ground. That Curtiss Robin, fully restored, is now a part of the collection of The Museum of Flight at Boeing Field, in Seattle.

The Museum of Flight consists of an East Campus and a West Campus which contain two Galleries, a Barn, a Wing, a Pavilion, a Theater, and two Cafés. In other words, it is a large museum and, before you begin your tour, be sure to get a map and devise a plan to maximize your enjoyment of this excellent museum.

Author’s note. I had a Gulfstream 650 trip to Boeing Field last summer and took the opportunity to visit The Museum of Flight. I hadn’t been there for many years and found that it has really grown. I took a lot of photos, but I decided not to write about the museum as it doesn’t fit the main mission of this blog, which is to give exposure to smaller and lesser known aviation museums. The Museum of Flight is well known and is certainly not small. Fast forward to our current circumstances, when it is not possible to visit a museum. With no other resources available this month, I decided to write about the Museum of Flight. I enjoyed writing about this great museum, but it is so large that this is just a brief overview of what you can see there. We will see what next month brings.

I first visited this museum in the 1970s. At that time, it was just few displays in one small building with several planes parked out front. Today it has grown into one of the largest aviation museums in the world. —------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

T.A Wilson Great Gallery

As you enter the Museum, the T.A. Wilson Great Gallery is just to the left of the main lobby, and is a good place to start the tour. Entering this large, bright, and very dramatic looking Gallery, you notice right away that this is an eclectic collection, not associated with any specific era or category of aircraft.

The mission of the Museum of Flight is to provide a large and diverse collection of aircraft and space craft for education and research, and that size and diversity is clear throughout the museum. In this photo you can see a group of children seated beneath the Blackbird. Most museums consider education a large part of their mission, but at the Museum of Flight, you see evidence of their education initiatives throughout your tour. This is also, of course, a great place for adults and children to come and just enjoy looking at airplanes.

One plane that immediately caught my eye was this Boeing 80A-1 trimotor. Along with the better known Ford and Fokker tri-motors (as well as the Junkers Ju-52), the Boeing 80 ushered in a new era of passenger transportation in the 1920s. The Boeing 80 was introduced in 1927 and could carry 12 passengers. Unlike the Ford and Fokker, the Boeing was a bi-plane, designed to serve Boeing Air Transport’s airmail route from San Francisco to Chicago. Stops along the route were at small, and often high-altitude airports, and the bi-plane configuration provided the needed takeoff performance. Boeing soon produced the upgraded 80A model, which was powered by Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines and could carry 18 passengers. In 1930, Boeing Air Transport introduced the first flight attendants on the 80A, which was a popular move and a “hostess” soon became standard throughout the industry. Only 16 of these aircraft were built and their use was rather short lived. They were replaced by the more advanced Boeing 247 in 1934, about the time that Boeing Air Transport evolved into United Airlines. After its airline career, this Boeing 80A was used as a cargo plane in Alaska for several years and then abandoned. It was recovered from a dump in 1960 and restored. It is the only surviving example of the type.

Lockheed M-21 Blackbird. Note the D-21 drone mounted on top.

Dominating the Great Gallery is a Lockheed M-21, a variant of the A-12, which was the first Blackbird built. Later models were designated the SR-71 and different code names (such as Agboard and Oxcart) were used, but all models were very similar, and Blackbird refers to all of them. A total of just 50 of all variants were built and only 86 pilots ever flew them. One of those few, Cal Augustin, is an old friend and I asked for his impressions of operating this amazing plane.

“The SR-71 was a fun plane to fly. Always exciting and it kept you on your toes. Easy to land with big struts so it was hard to make a bad landing…but not impossible. It is, without a doubt, the most difficult to refuel. Half way through refueling you would reach the weight where military thrust was not enough and you would fly the rest of the refueling with afterburner on one engine and idle thrust on the other engine, using the engine that was reduced to idle to control your speed. That is why there was a requirement to have had air refueling experience before you could apply for the program. Each flight was a lengthy production, starting with a very detailed weather briefing, a low residue meal, a physical, and getting into the suit. We would show up 3 hours before takeoff time. The plane was preflighted by another crew and left in the cocked position so after you were in, it was ready for engine start. After takeoff you climbed to the mid-20s and went right into air refueling. Each crew had their own way of doing things and handling emergencies, so, if your navigator was sick, you didn’t fly and vice versa. It was a nice way to finish up my flying in the Air Force”. Thanks Cal!

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

There were just two M-21 versions built. As you can see, their mission was to carry a D-21 drone on top. The drone would be launched at altitude and fly a pre-programed photo mission over hostile country (it was designed specifically to overfly China). When the mission was complete, the camera would be dropped by parachute and the drone would self-destruct. The concept had many difficulties and only four test missions were flown. The fourth resulted in the drone hitting the mothership, which then crashed. The Air Force later tried launching the D-21 from B-52s, but that effort was not successful either, and the program was finally cancelled. A total of 38 D-21 drones were built. Of the 17 that remained after testing, a number are on display in museums (and a portion of one that was lost on a mission is displayed in a museum in China). As the Museum of Flight has the only remaining M-21 Blackbird, this is the only place where you can see a D-21 displayed as it was originally carried.

The Blackbird was designed by Kelly Johnson at Lockheed’s Skunk Works during the 1950s and first flew in 1963. All things considered, it is, in my opinion, the most amazing plane ever built.

Turning from the Blackbird to look at the Curtiss Robin from the opening story, we get the full effect of the wide variety of aircraft and vintages in this amazing museum. Introduced in 1928, the Robin was a sturdy and practical aircraft that carried cargo or two passengers in an enclosed cabin. Powered by the reliable Curtiss OX-5 engine, Robins were involved in a number of notable events. A Robin, for instance, was the first aircraft flown by Cubana, Cuba’s national airline. In 1929, Dale "Red" Jackson performed over four hundred continuous slow rolls in his Robin. He later spent 27 days aloft to set an endurance record. In 1935, Fred and Al Key, in another Robin, broke that record, spending a month aloft. Their air refueling was accomplished from another Robin. Perhaps the best know flight of a Robin was that of Douglas “Wrong Way” Corrigan. He owned a beat-up old Robin that had an engine that he put together from parts of two other engines. It leaked fuel and he had trouble getting an airworthiness certificate. Undeterred, he flew it from California to New York and requested permission from the Bureau of Air Commerce to fly the Atlantic. His request was denied because of the poor condition of his plane. He then announced that he would instead fly non-stop back to California. On July 27th, 1938, he filed a flight plan to California and took off from Floyd Bennet Field at 5 AM. He turned East and just kept going, landing in Dublin, Ireland 27 hours later. His plane had such a bad fuel leak enroute that he cut a hole in the cockpit floor to drain the puddle of fuel that was making his feet cold. Corrigan claimed that a bad compass caused him to fly the wrong way and being in clouds most of the time, he didn’t realize that he was over water. He was treated as a hero, and became an instant legend, never admitting whether or not he had planned to fly the Atlantic all along.

Before leaving the Great Gallery, I’ll mention this 737-200, which I have flown. The 737, in spite of the problems of the 737 Max, is the most successful airliner of all time. The 737-100 entered service with Lufthansa in 1968, followed shortly by the 737-200 with United. These models had Pratt and Whitney JT8D engines, as on the earlier 727. In 1984, the -300/400/500 series, with CFM high-bypass turbofan engines, entered service with USAir. The third generation, “NG”, with a larger wing and advanced glass cockpit was launched in 1997. The fourth generation, “MAX”, with the CFM LEAP engine, entered service in 2017. The 737 originally carried around 85 passengers while current versions can hold up to 215 passengers. Over 15,000 737s have been ordered with almost 11,000 delivered, making it the most produced airliner ever.

Aboard the USAir 737, you can view the original cockpit and the business class seats serve as an educational facility, showing an “in-flight” movie about commercial air travel.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

J. Elroy McCaw Personal Courage Wing

The Personal Courage Wing contains WW-I and WW-II displays. Here you will again see many beautifully restored aircraft, with some displayed in period settings.

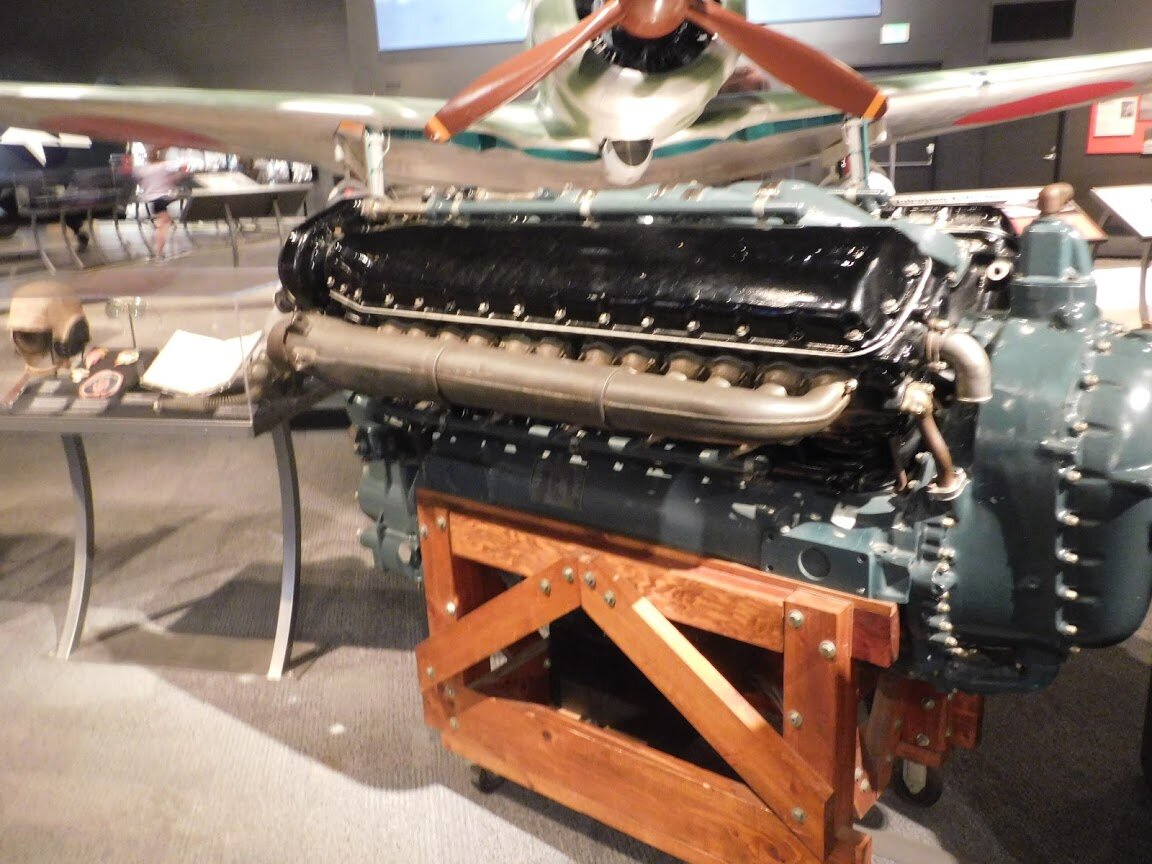

This North American P-51D Mustang is a great example of the high quality of restoration on display. Designed in 1940, the Mustang was originally powered by the Allison V-1710 engine. This engine gave the P-51 limited capability at higher altitudes and it was soon replaced by the Rolls-Royce Merlin. By the time the P-51D (the most numerous of the P-51s) entered service, the Army Air Corps was conducting daylight bombing raids deep into Germany and the long range of the P-51 made it a perfect fighter escort for B-17s and B-24s.

(NOTE- Reader Robert Walter sent this additional information about the P-51 engine- “The production Mustang was powered not by a Rolls Royce Merlin, but by a Packard Merlin (extensively redesigned for mass production and with some significant hardware changes (Carb, supercharger, indium plated bearing surfaces) and upgrades (though most of these were folded back into the R-R produced units). The Packard Merlin was built in Detroit, and besides the Mustang, it found its way into some P-40s and Lancasters.” Thanks Bob! I always try to add as much detail to the blog as possible, but there are obviously limits to how deep to go, especially on the subject of engines. This point about who built the P-51 Merlins (under license from Roll-Royce), is an important detail. Tony)

An interesting aspect of how this Mustang is displayed is that various panels are open, such as this access to three of the M2 Browning machine guns. The guns on the P-51D were mounted at a different angle than earlier models, eliminating most of the previous jamming problems. From the way the P-51 guns are displayed, you can get a good idea how the .50 caliber Brownings operated and were serviced.

Dramatically displayed on a deck of Marston matting, this Republic P-47D Thunderbolt was repatriated from Brazil in 1976 and re-built in California. The P-47 first flew in 1940 and quickly became a popular fighter. With the powerful Pratt and Whitney R-2800 engine, the Thunderbolt served in many roles, at both high and low altitude and in all theaters. It was the most produced piston powered fighter of all time, and served well into the 1950s. It also served in the military of numerous other countries.

A rarely mentioned product that greatly contributed to the war effort in WW-II, was Marston matting. As displayed here, Marston matting is made up of steel strips that are linked together and then rolled up. It could be quickly rolled out to make a runway, and even after a permanent runway was built, the matting was often used for taxiways and parking areas. During WW-II, a 5,000’ runway could be built in two days. This technique was also used in Korea and Vietnam and even at Tempelhof Airport during the Berlin Airlift. Marston matting parking areas still exist at many airports, I was parked on matting in Düsseldorf just a few years ago.

Most museums have models on display and I’m always impressed by the quality of modeling. This collection of over 400 planes from WW-II (virtually every plane that played a role) is one of the best. The 1/72 scale models were built by Doctor Logan Holtgrewe from kits and, if a kit wasn’t available, were scratch built.

On the second floor of the Personal Courage wing, we find WW-I aircraft. On its own, this gallery is as big as the entirety of many museums we have visited, with ten aircraft at ground level and eight more ‘flying’ above.

The Royal Air Factory S.E.5 (Scout Experimental 5) entered service in 1917. At first, it was not universally liked by pilots, but its speed and ruggedness soon made it an effective fighter. Along with the Sopwith Camel, the S.E.5 helped the allies maintain air superiority for the last two years of WW-I. The type was flown by two American units and plans were developed for the Curtiss Aeroplane Company to build the S.E.5 in the US. The war ended before production started, and virtually no American built aircraft were flown in Europe during the First World War.

Today, there are six original S.E.5s on display. The only one in the US is in the Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio. The Museum of Flight’s reproduction was started in 1971 in Florida and completed in 1988. It is one of only a few replicas ever built (see issue 4 of this blog for a dramatically displayed S.E.5a in the Aviation Heritage Centre, Omaka, New Zealand https://aviationhistorymuseums.com/blog/2019/8/20/omaka-aviation-heritage-center-blenheim-nz ).

As in most museums, the majority of WW-I planes on display here are reproductions, but the Museum does have four original WW-I aircraft. Built in 1914, this Caproni Ca.20 is displayed in amazing original condition. It was stored by the Caproni family for 85 years and, when found, it was on display in a monastery. It is still in the condition it was found in- basically original, and the worn fabric covering is many years old.

Built in 1914, the Caproni Ca 20 was a development of the Ca.18 reconnaissance airplane. It showed signs of being an excellent aircraft, but the Italian government instead wanted Caproni to concentrate on building bombers. This is the prototype, and the only example built. All of the parts on the plane (except the tires, which were eaten by mice) are the original parts, making this an incredibly unique display.

The Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” was the most widely used trainer for American pilots during WW-I. After the war, numerous surplus Jennies were available on the civilian market (including a new one, in a box, that Charles Lindbergh bought in 1923). Reliable, and easy to fly and maintain, the Jenny became the best-known plane flown by barnstormers in the 1920s, and into the 1930s. This Jenny was built from original plans, using period materials and methods by Paul and Lucy Whittier. Although technically a reproduction, the Whittier’s started with a bunch of battered parts of a Jenny that was manufactured in 1917. The JN-4 is dramatically displayed without any fabric covering, giving a rare look into the structure of a WW-I era plane.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The William E. Boeing Red Barn

The history of The Museum of Flight goes back to 1965 when displays were placed in the Seattle Center (site of the 1962 World’s Fair). Looking for a permanent home, the Museum obtained a 99-year lease on the current site in 1975. The first building here was The Red Barn, which was the original building of the Boeing Company. It was moved by barge from its original location at a shipyard site in Seattle. A small museum was started and expanded, and the building was restored in 1983.

The Red Barn displays the history of Boeing, and aviation in general, from the early 1920s up to the beginning of WW-II. Several areas of the Barn have dioramas including the original workshop and office areas, as well as the original drafting room.

Also featured in the Red Barn are original artifacts and photos detailing the pre-war history of Pan Am and the era of the great flying boats. There are numerous boards that make fascinating reading about the development and history of Pan Am. One especially interesting story is that of Captain Robert Ford and his crew of a Boeing 314, “Pacific Clipper”. They left Los Angeles on December 1st, 1941 to fly a scheduled trip to New Zealand and back. On December 8th, as they were approaching New Zealand, they picked up a radio message about the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. Upon arrival, they were given instructions to continue west bound, to New York. Having no charts for that side of the world, they visited libraries to obtain whatever maps they could find. Basically, they were on their own, traveling around in a world at war, doing their own maintenance, and paying for their own fuel and other necessities. They finally arrived in New York 36 days after leaving Los Angeles.

The year 1927 was a landmark year in aviation. Not only did Lindbergh fly the Atlantic, but there were many other records set, as well as many failed attempts to cross the Atlantic and the Pacific (see One Summer, America, 1927, in “Suggested Reading”, below.) The entire two floors of the Red Barn contain numerous displays like this that can be quickly glanced at, or you can spend hours reading the well-written and illustrated glimpses of history.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Before Crossing the bridge to the West Campus to conclude our visit in the Aviation Pavilion, I’ll just mention several other areas of the museum. There are many activities and tours available, including simulator rides, as well as a theater and an extensive library, all too much to cover properly in this blog. The museum website covers all the available additional tours and much more information. The only main section I did not cover in this blog is the Space Gallery.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Aviation Pavilion

The 140,000 sq.ft. Aviation Pavilion is home to 19 full sized aircraft. Once again, this is an eclectic collection, ranging from a Boeing 247 to the Boeing 747 prototype and from a Douglas A-4 Skyhawk to a Boeing B-29. It really is quite an overload of things to see, and, once more, you could spend a full day in this Pavilion. To that end, by the way, there is a gift shop and café in this building.

With large planes, and many you can go into, this is my favorite part of this museum. The building is open on one side and is built very much like a hangar. The Pavilion is not laid out in any particular order- obviously the size of all these planes dictated how they could be arranged. With no particular plan, I gravitated to two classic airliners, displayed side by side, a United Airlines Boeing 247 and a TWA DC-2.

The Boeing 247, by a small margin, was introduced first. As we discussed in the Great Gallery, the first ‘modern’ airliners were three tri-motors from Boeing, Ford and Fokker. Introduced in the late 1920s, these planes were the first actual cabin class planes. In late 1933, Boeing introduced the 247, which again made large strides in comfort and safety. The airlines all wanted this new model, but, as Boeing had ownership in United Airlines, United was given the first 60 delivery positions. Only 75 Boeing 247s were built, and only four remain.

Unable to obtain the new Boeing 247 and keep up with United, Howard Hughes, over at TWA, contacted Donald Douglas with a request for a comparable airliner. Douglas decided to aim for a more advanced plane and produced the DC-1, at the end of 1933. The biggest difference was Douglas’ choice of Wright Cyclone engines. With variable pitch props, these powerful engines gave the DC-1 the ability to fly on one engine, even up to 11,000 feet. It also had a larger cabin that could carry 14 passengers versus 10 for the Boeing 247. The one DC-1 built provided the basis for the DC-2, which was introduced in 1934. Although the DC-2 was fairly quickly replaced by the DC-3 (1936), 192 were built. They were popular with airlines throughout the world as well as with the military. Although displayed in TWA colors, the DC-2 in the museum was flown by Pan Am and was kept in the air by the Douglas Historical Foundation until 1997. Approximately eight DC-2s exist, mostly in museums in other countries. This is likely the only DC-2 on display in the US.

This 727-100 was the original 727 built by Boeing. It first flew in February, 1963 and was certified in December of that year. It was delivered to United for crew training which allowed Eastern Airlines to be the first to put the 727 into scheduled service in early 1964. This is the second Boeing in this museum that I have flown, although, on this one I was the flight engineer. Does that count?

This 727 served with United until 1990. Nearing its retirement, the Museum of Flight asked United to donate the aircraft to the Museum. United agreed, but removed numerous parts, including engines, before it was turned over. It took 25 years of restoration at the Museum's Paine Field Restoration Center plus the acquisition of another two 727s to put it back to original condition. In March of 2016, it made the short flight over to Boeing Field to become part of the Aviation Pavilion.

By 1943, it was clear that jet propulsion was the future of air power, particularly for strategic bombers, and the Army Air Corps published a list of requirements. Boeing won the competition over North American, Martin and Convair. They drew a lot upon German research and design in proposing the XB-47. In 1946, the Air Force (which was still the Army Air Corps until 1947) ordered two prototypes, and the B-47 entered service with the Strategic Air Command in 1951. Operational until 1965, over 2,000 B-47 Stratojets were built. Very successful as a strategic bomber, the B-47 also provided the research and experience to design and build the first generation of jet airliners, especially the Boeing 707.

The B-47 served in many roles other than as a strategic bomber, and the Museum’s B-47 was designated a WB-47, flying weather reconnaissance missions for the US Navy into the 1970s.

Part of the B-47 display is dedicated to recognizing the contribution of Tex Johnston in the development of Boeing jet aircraft. Alvin "Tex" Johnston began his flying career as a barnstormer and was a test pilot during and following WW-II. After the war, he flew the rocket powered Bell X-1, which he helped design. Joining Boeing as a test pilot in 1948, Johnston achieved numerous milestones, including piloting the first flight of the B-52. He may be best known for performing a barrel roll in Boeing's prototype 707 (367-80) during a demonstration flight over Lake Washington in 1955.

A number of exhibits in the museum, including this Concorde, are open to visitors. First flown in 1969, Concorde entered scheduled service in 1976. Originally, many airlines placed orders for Concorde, but in the end, only British Airways and Air France bought the plane, both with substantial government support. Braniff Airways and Singapore Airlines each operated Concorde, under lease, for a short period of time. For two years, Braniff continued the British Airways London to Dulles flight on to Dallas, but at sub-sonic speeds. In July of 2000, an Air France Concorde crashed on takeoff from Charles de Gaulle airport, in Paris, the only accident in the 27-year history of Concorde flights. By 2003, both British Airways and Air France had decided to withdraw the plane from service. Twenty Concordes were built and the remaining nineteen are all displayed in various museums. This Concorde (G-BOAG -serial number 214) flew the final Speedbird 2 flight from New York to London on October 24th, 1973 and returned to New York ten days later. On November 5th, it departed JFK for Boeing Field. With special permission, it made a rare over-land supersonic flight while over Northern Canada. The flight set the record for New York- Seattle in 3 hours 55 minutes 12 seconds. G-BOAG flew a total of 16,239 hours before making its final landing at Boeing Field.

The Concorde’s cockpit and 100-seat cabin can be viewed in their original condition.

Almost lost among all the large airplanes in the Aviation Pavilion is this beautifully restored Boeing B-17. Like many other aircraft in the collection, this Flying Fortress, serial number 42-29782 has been restored to flying condition. In fact, it is the only flyable F model in the world. Built in 1943, it began its life at various training bases, including at Moses Lake in Washington. It was flown to Europe in 1944, but did not see combat in its three months in England. It returned to Florida and resumed its role as a trainer for the rest of the war. After WW-II, like many surplus aircraft, 42-29782 found its way into civilian life. For five years it sat as a war memorial in a park in Arkansas. It was purchased and brought back to life, as a fire fighter, crop sprayer, air tanker, and, eventually, movie star. It appeared in three movies, including Tora Tora Tora and Memphis Belle. It traveled to England to shoot Memphis Belle and amassed over 50 hours of flight time during the shoot. In 1991, she returned to Seattle, and the long process of restoration began. Almost complete, the 20-year restoration has been accomplished completely by volunteers.

The Boeing 747-100 first flew in February, 1969, and entered service with Pan Am in January, 1970. The first 747 ever built, serial number 001, was used as a Boeing test-bed throughout its history, and one of its final uses by Boeing was testing of the engines for the 777. That 747 is now on display at The Museum of Flight.

This testbed 747 is one of the many aircraft that is open to tour inside. Everything from delicate temperature and vibration monitoring instruments, to various galley configurations remain in the interior. These barrels, for instance, contain water, and, during testing, they were filled and emptied to simulate various passenger and cargo loads.

One interesting and important role of this 747 was the design and testing of inflight refueling systems. The rear of the fuselage has a full re-fueling boom set-up, which required extensive structural modifications to install. While no fuel transfer took place during testing, the entire system worked exactly as it would in eventual production on the KC-135 and other tankers. Many aircraft were hooked up to the 747 and tested for their air-refueling capability, including the B-52, SR-71 and the F-4.

As the 747 was being designed, Boeing had to address where they would build this huge aircraft. They explored 50 different locations around the country but, in the end, decided to build it near their home town of Seattle. They settled on Paine Field, in Everett Washington, thirty miles north of Seattle. Originally built in the 1930s as a WPA project, Paine Field became a military base in WW-II to support local shipbuilding as well as Boeing. By the 1960s, the Air Force was greatly reducing its presence at the field, and civilian uses were being developed- ideal timing for Boeing. The factory that Boeing erected turned out to be the largest building, by volume, ever built. Design and construction of the building was as complicated as the plane that was to be built there, and the original mock-up of the 747 was in place even before the roof was completed. To honor the location, Boeing named their first 747 “City of Everett”.

I have mentioned a few times about how much information is contained in this museum. If you wanted, you could spend the better part of a day just browsing the displays in and around this historic 747.

There are many other interesting aircraft in the Pavilion, as well as the rest of the museum; and I would have liked to write about them all. Here in the Pavilion is the first jet powered Air Force One (a 707) that you can go inside, a B-29, the prototype of the 737, and many others. There is also a portion of a FedEx 727 that gives visitors a look at the entire process of cargo operations. This is why I was reluctant to try to write about this world class museum, it’s impossible to do it justice in a blog of this length. You will just have to come and see it yourself!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To learn about what to do in the local area, museum hours and costs as well as books to read and other interesting odds and ends, keep reading! At the end you will find a photo gallery of the entire museum.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

When back to normal, the Museum Hours are-

Open daily from 10:00 AM - 5:00 PM. The first Thursday of each month, the Museum is open from 5:00 PM - 9:00 PM with FREE ADMISSION. Closed Thanksgiving and Christmas Day.

Child (4 and under) FREE

Youth (5-17) $17

Adult (18+) $25

Senior (65+) $21

Members FREE

Various Group, Military, AAA and airline discounts are available

FLYING IN

KBFI Boeing Field. There are five spaces available for fly-in parking at the Museum, for General Aviation aircraft only. No twin engines, business aircraft or rotorcraft without prior approval. For visits between 0700 -1700, call security to request access at 206-920-9770.

LOCAL ATTRACTIONS

The Seattle area is a great place to visit, with lots to do. Here’s a few places not to miss- Pike Place Market. Opened in 1907, this is still very much an old-time fish and produce market with a lot to see and do. It is downtown, near the waterfront, with many other stores and restaurants in the area

Pike Place Market. Social distancing rules might be a little tough here.

A fun thing to do on the waterfront is to take a ferry ride. The Seattle - Bainbridge Ferry is a pleasant 45-minute ride across Puget Sound and Bainbridge Island is a great place to visit. There are restaurants, museums, galleries and antique shops in walking distance from the ferry terminal.

WHERE TO EAT

With a museum this large, you will probably spend all day. Luckily, The Museum of Flight has two cafes. I didn’t have time to sample the food, but the menus looked interesting and there was plenty of room in both of them to enjoy a meal.

SUGGESTED READING

I recently re-read Bill Bryson’s One Summer- America, 1927. This very interesting book centers around Charles Lindbergh, Babe Ruth and Henry Ford, but touches on many other events of that year. The chapters on Lindbergh give many small insights as well as thoroughly covering all the other people involved with attempts to fly the Atlantic. It thoroughly describes Lindbergh’s life after his milestone flight, and how he, and his plane, were mobbed wherever they went. An informative and easy to read history of this seminal year.

This section is usually reserved for book recommendations but I recently came across a magazine, The Aviation Historian, that I highly recommend. The magazine is published in smaller format (about the size of a National Geographic), which I find convenient. Published quarterly, it contains a wide variety of well-researched and well-written articles on a wide variety of subjects, and the quality of photographs in each issue is very high indeed.

Boeing 377 Stratocruiser. Photo courtesy of The Aviation Historian

The Aviation Historian is published in the UK, but covers aviation world-wide. The article that led me to the magazine in the first place was on TWA’s Martin airliners. Mentioned in the article is the Martin 202 in the Aviation Hall of fame in Teterboro, the first blog in this series.

Ford Tri-motor. Photo courtesy of The Aviation Historian

The cost of a subscription to the US is a little high, due to international postage, but very much worth it.

http://www.theaviationhistorian.com/index.htm

MUSEUM WEBSITE

https://www.museumofflight.org/

UP NEXT

TBA

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

Original Tower, Floyd Bennett Field. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service

Floyd Bennett Field (the departure field for “Wrong Way” Corrigan’s flight across the Atlantic) was the first municipal airport in New York City. It opened in 1928 and became a Naval Air Station during WW-II. Today it is a part of the Gateway National Recreation Area. It is no longer open as an airport but the runways and many of the original airport buildings remain. The control tower and a restoration hangar are open for tours at selected times. It’s an interesting place to visit.

Restoration Hangar. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

A quick note about research. A wide variety of sources are used in writing this blog, and, as this is basically an opinion piece, not an academic work, sources are not usually cited. Obviously, though, my primary research is on the museum web-site. I never announce my visits beforehand, but I often get helpful answers to questions from museum staff while I am writing. Wikipedia, which, when used with caution, can be an excellent resource, is frequently consulted. I occasionally get corrections and additional information from readers, and that is greatly appreciated. I also refer to books in my personal library, and I usually purchase a book or two at the museum shop, especially if (as in the case of Omaka in New Zealand), they publish a book about the museum. In this research, I sometimes come across conflicting information (such as how many aircraft were built). I always try to resolve the discrepancy with further sources, and information in this blog aims to be as accurate as possible.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

PHOTO GALLERY

click any photo to enlarge

T.A Wilson Great Gallery

J. Elroy McCaw Personal Courage Wing

The William E. Boeing Red Barn

The Aviation Pavilion

Museum Exterior and Boeing Field

Issue 12, Copyright©2020, all rights reserved. Except where noted, all photos by the author