The Smithsonian Udvar-Hazy Center, Chantilly VA (Part 2)

Issue 29 A visit to the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian Chantilly VA (Part 2) November 2021

--------------------------------

The bespectacled 70-year-old, dressed in a coat and tie, maneuvered his 1972 Shrike Commander to position himself over the runway. Satisfied with his line-up and speed, he reached down and, in quick succession, cut the mixtures and feathered both propellers. He immediately pulled aggressively on the yoke, not easing up until he was over the top of a loop. As he pulled out at the bottom, he turned the yoke to the left, initiating a perfect eight-point roll. As soon as he completed the roll, he made a 180-degree left turn to line up with the runway, kicking the rudder a few times to bleed off a little excess airspeed. He touched down on the numbers, first on the left wheel, and then on the right wheel. With both engines still stopped, he turned the plane to the right and taxied to a stop, right in front of thousands of cheering spectators.

Bob Hoover executed this air show routine in his Shrike Commander for almost 20 years. That plane is now on display at the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Center at the Dulles Airport in Chantilly, VA.

—————————————————————————

There are a number of aerobatic planes in the museum, most of them are creatively displayed hanging high above.

This Loudenslager Laser 200 was built for Leo Loudenslager in 1971. It was designed by Clayton Stephens and originally named the Stephens Akro. From 1971 to 1975, Loudenslager made numerous changes to the plane making it lighter, stronger, and more powerful. He eventually cut the fuselage in half and built an entirely new front end, naming the resulting craft the Laser 200. During this period Loudenslager was moving up in the national and international aerobatic standings and, in 1975, he won his first U.S. National Championship. He went on to win the National Championship six more times, a record that still stands. In 1980 he won the World Aerobatic Championship in this plane. The Laser 200 has a single, shoulder mounted wing, a departure from bi-plane designs, such as the Pitts. It set the standard for the design of aerobatic aircraft that is still emulated today. Leo Loudenslager died tragically in a motorcycle accident in 1997 and his plane was donated to the Smithsonian in 1999. There was some initial push back about displaying the plane with the “Bud Lite” logo, but the museum stood its ground, and still displays the Laser 200 with its long-time sponsor as part of the paint job.

This Grumman G-22 Gulfhawk II was built for air show pilot Al Williams in 1936. Williams was a former Naval (and later Marine) aviator who had set world speed records while on active duty. After leaving the military, Williams flew the Gulfhawk I in air shows from 1930-36 and the Gulfhawk II from 1936-48. In 1938 this plane was crated up and shipped to Europe where Williams flew in air shows in England, France, Holland, and Germany. In Germany, WW-I ace Max Ernst became the only pilot besides Williams to ever fly the Gulfhawk II. In return, Williams became the first American to fly the Messerschmidt Bf-109.

Al Williams flew his final air show in this plane at Washington National Airport in 1948, removed the stick, and presented the plane to the Smithsonian.

Bob Hoover flew Spitfires in WW-II. He was shot down over France (by German ace Siegfried Lemke) and spent over a year in a German POW camp. He eventually escaped, found a German airfield, and stole a damaged, but fueled, FW-190. After talking a stunned German mechanic into helping him start the plane, he flew to Holland and freedom. Hoover famously said that he could fly any plane if you told him what speed it landed at, and how to start it. After the war he became a civilian test pilot for the Air Force. One of his notable achievements was flying wingman for Chuck Yeager’s 1947 Bell X-1 flight, when it broke the sound barrier. Hoover eventually became a test pilot for North American and, in the early 1960s, began flying a P-51 in air shows. He also flew the T-39 Sabreliner in shows, transitioning to his famous North American Shrike Commander in 1973. He flew in his final air show at Luke AFB in 1999, at the age of 76.

Photo Courtesy of the Smithsonian

In April 2000 Hoover flew his Shrike Commander to Sun ‘n Fun, the Experimental Aircraft Association's (EAA) Lakeland, Florida fly-in. In 2003, he flew it for the final time, from Lakeland to Dulles, to present it to the Smithsonian.

——————————————————————————————

Several museums we have visited have sections devoted to space travel. I usually skip writing about these- they are a different area of flight and too big of a subject to do justice to in just a paragraph or two. At the Udvar-Hazy Center, however, there are several objects so significant that they should be mentioned.

On July 16, 1969, a Saturn V rocket lifted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. On top of the Saturn was a command module, with three astronauts aboard, as well as a lunar module, and a service module. The mission, Apollo 11, was the fifth crewed mission of the Apollo program and it would be the first to land a man on the Moon. The crew- Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins, had named the command module The Columbia and the lunar module The Eagle. After the successful lunar landing on July 20 (“The Eagle has landed” and “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”), the astronauts spent 21 hours on the Moon, and then flew back to the Columbia for the return trip to Earth. The capsule is in more or less the condition it was in after the mission splashdown and it is amazing to be able to stand next to such a great piece of aviation history. The capsule was delivered to the Smithsonian in 1971, after a tour of the U.S.

The space shuttle Discovery is arguably even more significant than the Columbia, mainly due to its longevity. Of the five launch capable shuttles built (a sixth was built as a test vehicle), Discovery flew the most missions and had the most hours in orbit (365). Discovery was the third Space Shuttle to fly into space, entering service in 1984. When it retired, in 2011, it had flown 39 orbital missions and traveled almost 150 million miles-more than any other orbiter. It shuttled 184 men and women into space and back, many of whom flew more than once, for a record-setting total crew count of 251. During its 27-year operational history, Discovery flew every kind of mission the Space Shuttle was designed to fly. It is displayed pretty much as it was in 2011, after it landed following the 133rd Space Shuttle mission. NASA transferred Discovery to the Smithsonian in April 2012 after a flight, atop a 747, over the nation's capital.

————————————————————————————————-

There are many WW-II aircraft in this museum and a number of them are displayed suspended from the ceiling. The numerous raised walkways allow great viewing and picture taking from various angles.

This Vought Corsair F-4U-1D, BuNo 50375, was delivered to the Navy in April 1944. It is displayed in the colors of Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-113 and named “Sun Setter”.

In the late 1930s, the Curtiss P-36 Hawk was one of the few front-line fighters available to the U.S. Army Air Corps. Although the design was modern, performance of the P-36 was lacking, especially compared to the British Spitfire and Hurricane which were coming on line. Curtiss re-designed the P-36 and the new model, the P-40 Warhawk, first flew in 1938. As one of the few fighters available at the onset of WW-II, the P-40 saw service in all theaters of the war. Although it was outperformed by later fighters such as the P-38 and the P-51, it continued to serve throughout the war, with over 13,000 built.

The P-40 was flown by the RAF and other Commonwealth nations as well as by the Soviet Air Force. Those nations named some P-40s Tomahawk and others Kittyhawk. This particular P-40E was built for the Canadian RCAF in 1941, and designated a Kittyhawk 1A. It served in Alaska defending against Japanese incursions there. It was declared surplus in 1946 and went through several private owners until winding up with an Explorer Scouts youth group in Mississippi. In 1964 the plane was donated to the National Aeronautical collection, transported to Andrews AFB and restored there by Andrews personnel. It is painted to represent an aircraft of the 75th Fighter Squadron, 23rd Fighter Group, 14th Air Force.

Built at the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, the N3N Yellow Peril was produced in two versions, a land plane and, like this one, a float plane. This N3N-3 had been based at Cherry Point NC and it was transferred to Annapolis in 1946. N3Ns were used for training at the Naval Academy all the way to 1961, making them the last bi-planes to serve in the U.S. Navy.

Major Richard Ira Bong was a Medal of Honor winner and the highest scoring ace in the U.S. military, scoring 40 victories in the P-38. Major Bong flew this particular P-38J during flight tests at Wright Field, Ohio, to evaluate a new engine control system.

I have mentioned in other blogs that it is inspiring to stand in front of historic aircraft and think of all the many brave pilots who have flown them. At this museum, you are reminded more about specific pilots, such as Bong, when viewing the historic planes. After all his heroics during WW-II, Bong died tragically test flying a Lockheed P-80 jet fighter, just four months after flying this P-38.

————————————————————————————

Most museums are involved in aircraft restoration but visitors seldom get to see that aspect of aviation history museums. The Smithsonian had the luxury of designing this large building from scratch and did a great job of including a restoration facility that is in full view. The area is named after the wife of Admiral Don Engen, who was an Administrator of the FAA and, later, Director of the National Air and Space Museum. The area, viewed from above, is large enough to have many aircraft undergoing restoration as well as a number of small shops for specialized restoration tasks.

If you visit on a weekday, you will be able to watch as museum staff work on various restoration projects. I visited on a weekend, with no restoration going on, but there was still plenty to see.

This nose section of a Martin B-26 Marauder, AAF serial number 41-31773, “Flak-Bait”, was on display for many years in the main National Air and Space Museum, in D.C. The rest of the aircraft was in storage but it is now going to be re-assembled and displayed as it was after its final mission. This is truly an historic plane, as it flew the most combat missions (206) of any U.S. aircraft during WW-II. The historic nature of the plane was recognized by General Hap Arnold and he included it in the inventory of the National Air Museum in 1949. It was transferred to the Smithsonian in 1960. This B-26 lived up to its “Flak-Bait” name- it has over 1,000 patched flak holes.

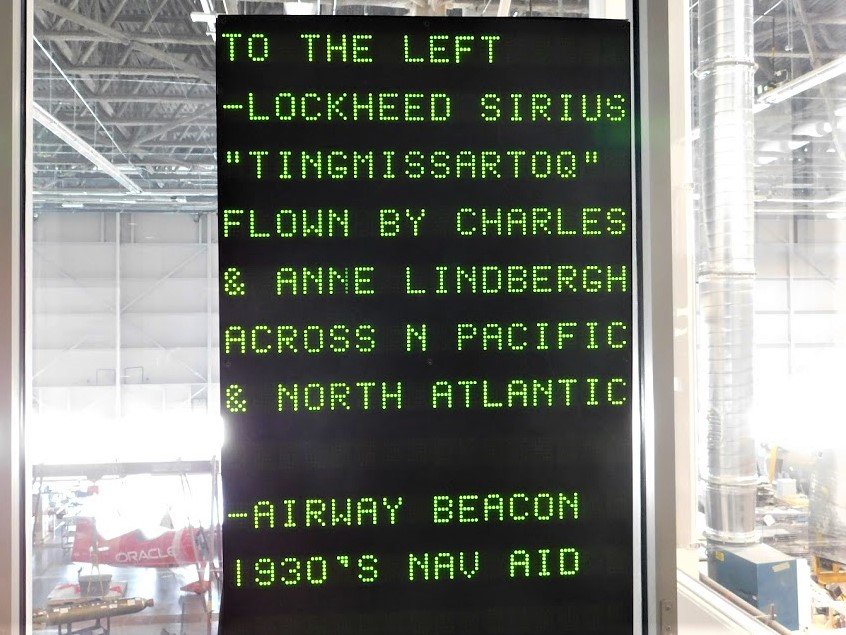

With a large number of items under restoration, the museum developed this changeable sign to let visitors know where to look and what they are looking at.

You can see the great variety of items under restoration, as well as how many historically significant planes will be added to the museum.

And, yes, they are restoring an X-Wing fighter from Star Wars!

————————————————————————————

The museum has a number of interesting German aircraft from WW-II. Many of these aircraft are partially restored and, when I visited, the entire section appeared to be undergoing a re-design. In spite of this, the planes are still visible and mostly well marked and interesting to view.

The aircraft fuselage on the left side of the above photo (plastic covered) is part of the only remaining example of a Horton Ho 229. This twin-jet (with Junkers Jumo engines) flying wing was one of a number of very advanced designs that were being built in Germany toward the end of the war.

Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian

Six prototypes of the Ho 229 were built and there were several successful test flights before a crash halted the program. The U.S. Army found four of the prototypes at Friedrichroda, Germany, in 1945. This airframe, Ho 229 V3, was the most complete and the Army had it crated and shipped to the U.S. It was delivered to what is now the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, MD in 1950. The center section has been restored, with plans to complete the full restoration.

The Arado Ar 234 B-2 Blitz was designed in 1940, but did not make its first flight until 1943 due to a delay in the availability of the Jumo jet engines. Over 200 of these planes were built. It was originally designed as a reconnaissance aircraft, but later models were also built as bombers. There were several four-engine versions built, the first four-engine jet to fly. The first operational mission of the Ar 234 was in August of 1944, a reconnaissance mission over the beaches of Normandy. The Arado’s altitude and speed (461 MPH) made it virtually impossible to intercept and the Ar 234 continued reconnaissance missions to the end of the war (it was the last German aircraft to fly over England, in April 1945). The reconnaissance missions gathered lots of intelligence, but it was all too little, too late.

This Arado Ar 234, serial number 140312, is the last surviving example of the type. It was shipped to New Jersey in 1945, reassembled, and then flown to Freeman Army Airfield in Indiana for evaluation. It was later flown to Wright Field in Ohio and, in 1949, it was transferred to the Smithsonian. Restoration was finished in 1989 and the Arado was displayed in the main museum downtown before being moved to Dulles.

Another plane produced towards the end of the war was this Dornier Do 335 A-0 Pfeil (Arrow). This two engine, push-pull, design was claimed by the Luftwaffe to have flown at 474 MPH in level flight which would have been the record for piston aircraft at the time (and faster than the Arado jet, above). Approximately 47 of these aircraft were built, with only a few actually being operational prior to the end of the war.

This Do 335, like the Arado above, is the only know example to survive. In fact, the two planes were both in a group of German planes shipped to the U.S. aboard the British aircraft carrier HMS Reaper, in 1945. The Dornier was sent to the Test and Evaluation Center, Patuxent River Naval Air Station, Maryland and was flight tested from 1945-1948 (another Do 335 was sent to Freeman AAF, but apparently did not survive). It was stored in Norfolk until 1961, when it was transferred to the Smithsonian. In 1974, this plane was shipped to the still operational Dornier factory in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany. It was restored by Dornier employees, many of whom had originally built the plane. It was on display in Germany until 1988, when it was shipped back to the U.S. and put on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center.

The Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet is another remarkable German “wonder weapon” that was operational during WW-II. This rocket powered interceptor was truly revolutionary- but very difficult and dangerous to operate. The rocket fuel was both corrosive and explosive and caused many accidents. The Komet only carried enough fuel for eight minutes of powered flight. The landing gear came off on take-off and once the fuel was burned, the Me 163 would glide to a landing on a skid. Test pilots were chosen from the ranks of glider pilots, including one of Hitler’s best-known test pilots, Hanna Reitsch. Reitsch made three powered flights in the Me 163, almost dying in a crash on the third.

Operationally, the Me 163 was not very successful, recording less than 20 kills. Besides the short range, the Komet only had one, rather slow firing, gun. Tactics developed were to rocket up vertically through a formation of bombers, who were usually at around 30,000’. The Komet would continue to about 35,000’ then dive on the formation. The climb to 35,000’ took four minutes, giving the pilot just four more minutes of powered flight, enough for about two passes on the bombers before running out of fuel and gliding back to base.

This Me 163, serial number 191301, was one of a batch of five that were sent to Freeman AAF in 1945 and it was given code F-500. In 1946 it was shipped to the Army Air Force testing center at Muroc dry lake in California for flight testing. After several non-powered flights there was some de-lamination of the wood wings and it was decided not to attempt powered flight. The Komet was stored until it was transferred to the Smithsonian in 1954.

Displayed in front of the Me 163 is its rocket engine, the Walter HWK 109-509. This engine was way ahead of its time, but very difficult to work with and keep operational.

This plane was one of a number we have talked about that was sent to Freeman Army Airfield in Indiana for testing. For more information about Freeman AAF, see below in “Museums are where you find them”.

——————————————————————————

The Udvar-Hazy Center has just about every category of aircraft on display and, as we have seen, many are unique. Here’s just a few more of the rare craft you will see here.

Piloted by Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones this capsule made the first around the world balloon flight in 1999, travelling 28,431 miles in 21 days.

Another record setting around the world craft on display is the all-composite, Burt Rutan designed, Virgin Atlantic Global Flyer. In 2005, Steve Fosset was the first to fly solo, non-stop, around the world in it. His record setting flight, starting and ending in Salina Kansas, took just over 67 hours.

Federal Express officially began operations on April 17, 1973, with 14 aircraft departing Memphis that evening. FedEx founder Fred Smith originally ordered 33 of these Dassault Falcon 20s, modified with a cargo door and a strengthened floor. This Falcon, “Wendy”, was the first of FedEx’s planes and it was donated to the Smithsonian in 1983.

The first of Waldo Waterman’s roadable plane designs was flown in 1934. Although no market developed for the design, Waterman continued to improve his idea, eventually building six versions. The planes contained standard parts from Studebaker, Ford, Austin, and Willys. The idea was to make the plane feel as much like a car as possible, as well as keeping the price down. This is the final version, the Waterman Aerobile #6 (finished in “Buick Blue”). It was FAA certified in 1957, but there was still no market for the plane and it was never produced. This is the only remaining example.

——————————————————————————-

On August 6, 1945, a B-29 piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbetts lifted off of Tinian Field in the Mariana Islands for a 1,500-mile flight to the mainland of Japan. On board the “Enola Gay” was a 10,000-pound nuclear weapon, named “Big Boy”. The six-hour flight to the target, the city of Hiroshima, went flawlessly and the mission was successful. Unfortunately, dropping the bomb did not have the desired effect and the war continued. Three days later a second bomb, named “Fat Man”, was dropped by another B-29, named “Bockscar”. The primary target for that mission was the city of Kokura. Kokura was obscured by smoke from conventional bombing and the second nuclear bomb was dropped on the alternate target, Nagasaki. The Enola Gay, flown by Captain George Marquardt, flew weather reconnaissance for that mission. The following day, Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced that Japan was accepting the terms of surrender (the Pottsdam Declaration), officially ordering a cease fire on August 16.

This B-29, serial number 44-86292, was built in Omaha and accepted by the AAF on June 14, 1945. It had been selected for this mission by Col. Tibbets while it was still on the assembly line. It was first flown to Wendover Army Air Field, Utah and, 13 days later, to Guam for bomb bay modifications, and then to Tinian.

After the war, the Enola Gay flew in atomic test missions on Kwajalein and Bikini Atolls, but did not drop any additional bombs. In July of 1946, the Enola Gay was flown to Davis Monthan and the decision was made to preserve the historic plane. In August 1946, she was transferred to the Smithsonian. The B-29 was stored at various Air Force bases until it was flown to Andrews AFB in 1953. With no place to store a plane of that size, the Enola Gay was left outdoors at a remote location at Andrews. By 1960, the plane had been vandalized and damaged by the elements. Smithsonian staff became concerned by the condition of the Enola Gay and, led by Paul Garber, began disassembly of the plane. It was moved to the Smithsonian facility in Maryland, where it languished for a number of years.

By the 1980s, several Air Force veterans began lobbying for the restoration of the Enola Gay. Walter J. Boyne became director of the National Air and Space Museum in 1983 and he made the restoration a priority. The restoration began in 1984 and, after 20 years and over 300,000 hours of work, the Enola Gay was finally put on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center, perhaps the most important aircraft in this amazing building.

————————————————————————————

I want to thank all the readers who have commented on previous blogs- the nice comments make it worth all the work. Reader Tom Accamando recently wrote that what these museums are all about is inspiring and motivating younger generations to enter the aviation and space industries. The Udvar-Hazy Center certainly does that.

----------------------------------------------

To learn about what to do in the local area, museum hours and costs as well as books to read and other interesting odds and ends, keep reading! At the end you will find a photo gallery of the entire museum.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

Open every day but December 25, 10:00 am to 5:30 pm

Parking is $15 (admission free)

FLYING IN

The museum is near, but not on, Dulles Airport (KIAD). Dulles has three major FBOs and each has full services including rental cars and, perhaps, a loaner car. If you don’t want to deal with Dulles, Leesburg (KJYO) is about 25 minutes away. Be aware that JYO is located within the boundaries of the Washington DC Metropolitan “Special Flight Rules Area” (SFRA) and special procedures are in effect. https://www.faasafety.gov/gslac/ALC/course_content_popup.aspx?cID=405&sID=641

LOCAL ATTRACTIONS

The area around the airport is, of course, all built up, but if you venture west, you will soon be in some beautiful rural areas. Quite close to the Udvar-Hazy center is a historic plantation, the Sully House (no, not that Sully). It is an interesting visit https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/parks/sully-historic-site/

WHERE TO EAT

As of this writing, the museum restaurant is still closed for renovations. There are numerous restaurants in the surrounding area.

SUGGESTED READING

Walter J. Boyne was an Air Force pilot, a director of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, and the author of over 50 books. As mentioned earlier, it was under his leadership that the Enola Gay was finally restored. I purchased his book The Smithsonian Book of Flight many years ago and I often pull it out to randomly page through it (as well as to look at the 737, which I have flown, on the cover). It is a large format book full of excellent photos, both of the museum’s collection of planes and historic photos. It has a great four page pull out with Keith Ferris’s amazing B-17 mural on one side and, on the other, a chart of 110 aircraft depicting the history of American aviation. Published in 1987, it is available at all the usual outlets, some at a pretty good price.

Bob Hoover’s amazing career spanned most of the 20th century and he participated in a wide variety of events during the growth of aviation. From barnstorming to war to test flying and air shows to supersonic flight, not only was Hoover there, but he was a stellar participant in all of them. Hoover’s autobiography Forever Flying tells all of his story and is a great read.

MUSEUM WEBSITE

The website is very extensive and full of lots of information, including many interesting videos. It can be cumbersome to navigate, but it is worth the time to explore.

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

As mentioned earlier, Freeman Army Airfield, in Seymore Indiana, was one of the AAF fields where captured enemy aircraft were sent for evaluation and storage during and after WW-II. The field had been the site of a multi-engine training base earlier in the war, but, by 1945, that training had ended, leaving six large and empty hangars.

Besides enemy aircraft, Allied aircraft were also sent to Freeman Field to evaluate against the enemy aircraft. The P-40 in the Palm Springs Air Museum (issue 26) was one of those aircraft. At the end of the war, General Hap Arnold recognized the need for a national aviation museum. He originally considered Freeman Field for this museum, with so many aircraft already there. The hasty war time construction of the hangars was deemed insufficient for a permanent facility and Freeman was dropped from consideration.

By the end of 1946, the evaluation program ended and the aircraft at Freeman were dispersed to museums throughout the country, to Davis Monthan for storage, or were scrapped and buried on the field. Many of the aircraft were sent to Wright Patterson AFB in Ohio to become part of what was to be the fulfilment of Hap Arnold’s vision- the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

Photo Courtesy of Freeman Army Airfield Museum

Founded in 1995, and opened in 1997, Freeman Army Airfield Museum features information about the evaluation center, as well as many aircraft relics that were literally dug up on the field. It also serves to recognize the many cadets who trained at Freeman during WW-II.

Photo Courtesy of Freeman Army Airfield Museum

Freeman looks like a great museum to visit. Even though they have no complete planes on display, it could be a future issue of this blog. For now, though, it kind of fits this category.

Photo Courtesy of Freeman Army Airfield Museum

Many thanks to Larry Bothe, Curator/Treasurer of the Freeman Army Airfield Museum, for the information about the museum.

Update- March 2022. I recently received a note from Larry pointing out that the museum added many new exhibits in 2021 as well as completing a substantial update to the museum website. https://freemanarmyairfieldmuseum.org/ I am looking forward to visiting this interesting looking museum in the near future.

————————————————————————————

PHOTO GALLERY

click any photo to enlarge

Issue 29, Copyright©2021, all rights reserved. Except where noted, all photos by the author