Cradle of Aviation Museum

Issue 37 A visit to the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City NY

On April 16 1912, Harriet Quimby took off from Dover England, aiming for Calais France. Less than a year earlier she had earned the first U.S. pilot’s license awarded to a woman and now her goal was to become the first woman to pilot an aircraft across the English Channel. She had been waiting for several days for foggy conditions to clear. On the morning of the 16th, with the weather only marginally better, she decided to give it a try. Flying a Blériot monoplane, she made a pass over Dover Castle to give the reporters gathered there a photo op then climbed to 6,000’, hoping to get above the fog. Unable to top the weather, she descended back down to try to find clear skies below. Her Gnome rotary engine sputtered during the descent, but finally restarted at 1,000’. Breaking out into the clear, she saw the French coastline. Unable to locate Calais, she landed on the closest beach, at Equihen-Plage. Local fisherman soon spotted her and carried her on their shoulders into town, where she received a hero’s welcome.

The next morning, she awoke expecting to see the newspapers praising her flight. Instead, the papers were filled with the news of the sinking of the Titanic, which had hit an iceberg early in the morning of the 15th. Already a well-known journalist, Harriet Quimby soon became a celebrated pilot, but her highest achievement, the crossing of the English Channel, was hardly noticed in the turmoil of the sinking of the Titanic.

Although it is not Quimby’s plane, the Cradle of Aviation Museum does have an original Blériot XI on display. It is likely that it is the first heavier than air, powered aircraft ever imported into the U.S. and it is displayed to honor Harriet Quimby.

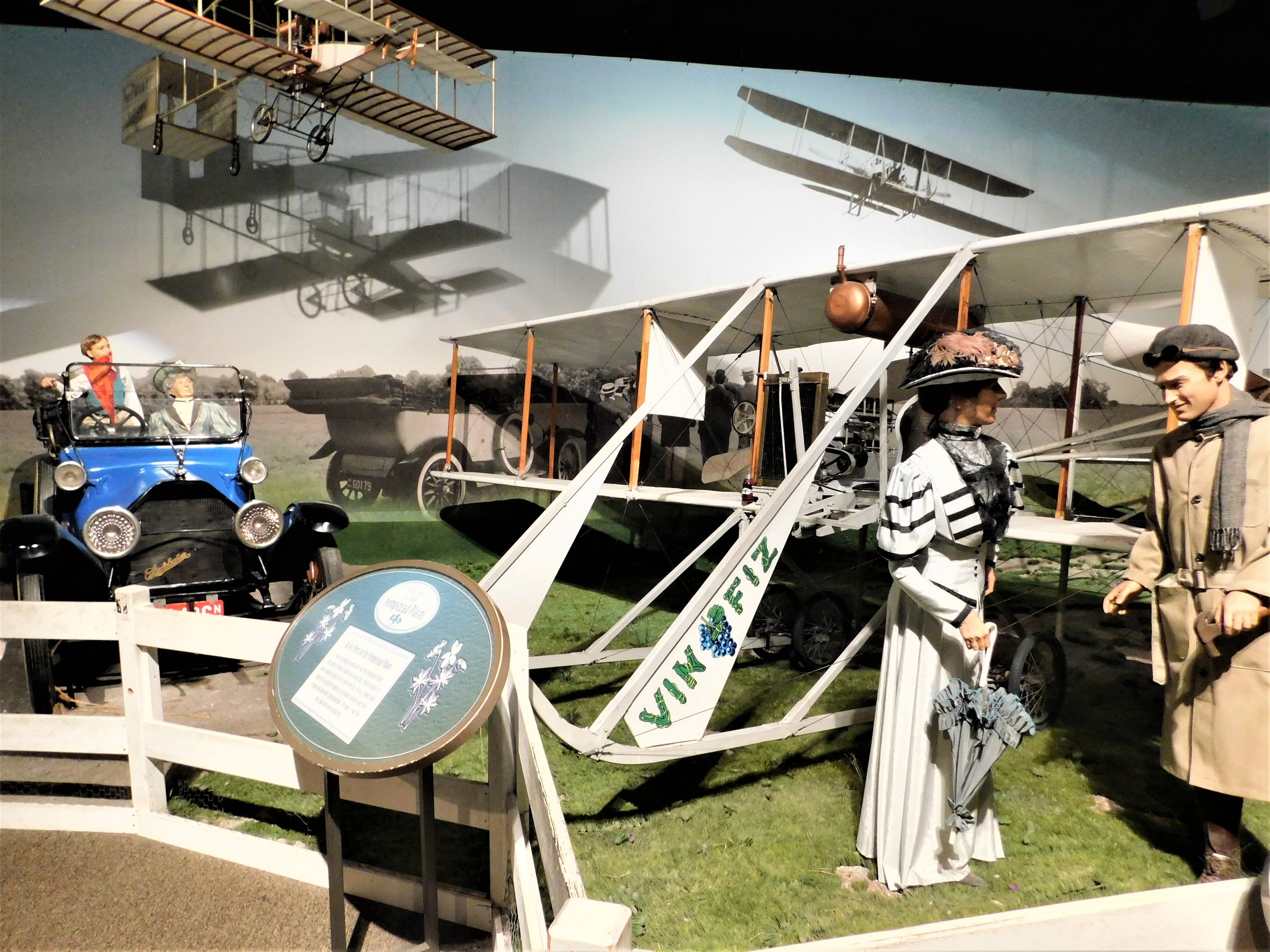

Re-creation of an iconic photograph of Harriet Quimby

Located on Long Island, on the site of historic Mitchel Field, the Cradle of Aviation (CAM) is a large museum with many significant aircraft on display. It will be a challenge to cover this great museum in just one blog, but, hopefully, you will enjoy the overview, and be motivated to go visit.

Long Island had been a center of aviation even before powered flight- in the 1800s it was the site of balloon and glider flights. From the earliest days of powered flight, it was home to pioneers of aviation such as Giuseppe Bellanca, Augustus Herring, and even Glenn Curtiss. The 1920s and 30s saw many record setting flights including those of Lindbergh and Chamberlain. Eventually, major aircraft manufacturers such as Grumman and Republic found a home on Long Island and that has continued all the way into the Space Age. The Cradle of Aviation Museum does an excellent job of covering the many people and manufacturers associated with Long Island.

The museum has its roots in the efforts of George C. Dade, the museum's first director, and Henry Anholzer of Pan American Airlines. The pair, along with a number of volunteers, began collecting and restoring aircraft in the 1970s. The planes were stored in hangar 3 and 4 of the old Mitchel AFB (closed in 1961), which is now owned by Nassau County. The first iteration of the museum opened in the unrestored hangars 3 and 4 in 1980. The museum grew from this beginning with just a few aircraft to its current display of over 70 aircraft. In the late 1990s, the museum was closed for rebuilding and it re-opened in 2002 with a very large and attractive premises, still incorporating the original hangars.

Mitchel AFB hangars 3 & 4, the original section of the museum

The large museum is nicely laid out in eras and there is a printed guide to follow along in historical order. The first section is titled The Hempstead Plains which sets the stage for showing the wide scope of aviation on Long Island.

Right away you can see the style of the museum, presenting aircraft in dioramas of their natural setting, as well as having well-designed descriptions of each display.

This replica of a Wright model B, which was modified and called the EX, represents the first aircraft to fly from coast to coast-named the Vin Fiz. Calbraith Perry Rodgers took off from the Sheepshead Bay Race Track at 4:30 pm, September 17, 1911. The trip took almost three months and included 75 stops,16 of which were crashes. Rodgers was accompanied by a support train and crew, which included Charlie Daniels, the Wright Brothers’ original mechanic. The trip was sponsored by the Armour Company to advertise their new drink- Vin Fiz, which was painted all over the plane. On his final leg from Pasadena to Long Beach, Rodgers crashed and was seriously injured. After three weeks in the hospital, he returned to his plane and taxied it into the Pacific Ocean, completing his coast-to-coast flight.

Otto Lilienthal, a German, is honored with this display of a replica of his 1894 glider. It is good to see Lilienthal recognized, as he was an important pioneer in wing design and was the first person to successfully demonstrate manned, heavier-than-air, flight. Between 1891 and 1896, he made over 2,000 glider flights from hills near Berlin (he unfortunately suffered a fatal crash in 1896). His work was studied by the Wright Brothers and was a great influence on them. Lilienthal is often referred to as the father of flight and it is unfortunate that he does not get more recognition for his work. Almost every museum we visit has a mention of the Wright Brothers (and rightly so) but it is rare to see a mention of Lilienthal. The Cradle of Aviation has a strong focus on education and this is an excellent example of that education.

This Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” was the first aircraft in the museum’s collection. Over 6,000 JNs were built and almost every American pilot who flew in World War One trained on the Jenny. After the war, many of these planes were made surplus and were purchased by barnstormers. This particular plane is the one that Charles Lindbergh purchased in Americus Georgia in 1923. He assembled the plane, learned to fly in it, and from there he took off barnstorming. Lindbergh visited museum founder George Dade while the plane was being restored and verified that it was his.

A JN-4 displayed to illustrate the structure of WW 1 era aircraft

A second Jenny on display is in one of the many artistic dioramas, this one representing a JN-4 under repair during WW 1. Mitchel Field was opened as Hazelhurst Aviation Field #2 in 1917. It was later renamed Mitchel Field after former New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, who died while training for the Air Service. Hundreds of pilots were trained here between 1917 and 1918, most in JN-4s.

You can see from this picture of Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, soaring above the Golden Age Gallery, that the museum is packed with aircraft and other displays. Although crowded, the entire museum is laid out in an artistic and pleasing way. Everything is restored and well maintained.

This "Spirit" is an original plane that was built in 1928 by Ryan as a "Brougham". It is very much identical to the original "Spirit of St. Louis" and it is one of two surviving sister ships of the Ryan Monoplane. This aircraft was used in the 1955 movie "The Spirit of St. Louis" and it was once flown by Lindbergh himself.

In 1927, Lindbergh departed from Roosevelt field, just a short distance away, on his historic flight. Both Mitchel Field and Roosevelt Field are well covered in the museum with various panels about their history.

Opened in 1916, Roosevelt field (named after Teddy Roosevelt's son, Quentin, who was killed in air combat during World War 1) was also the site of a training base as well as the site of a number of record setting flights. It closed in 1951. The two original hangars from Mitchel Field mark that location, but any vestige of Roosevelt Field has long been obliterated by development. One of the many knowledgeable docents I spoke with during my visit mentioned that there had been a monument to Lindbergh’s flight on Roosevelt Field. It was going to be moved from its historic location during construction of a shopping mall but it was saved through the work of a young college student. It is just a couple of miles from the museum and is well worth tracking down when you visit.

The marker is located very close to the exact spot where Lindbergh became airborne (on the second bounce, I think) on 20 May 1927, for his 33-hour flight to Paris.

Also located in the “The Golden Age of Aviation” gallery is this Grumman Goose. In 1936, The Grumman Aircraft Corporation, located in Bethpage, was approached by a group of businessmen who had summer homes on Long Island. They envisioned an aircraft that could shuttle them between their homes and a seaplane base in Manhattan. The resulting Grumman G-21 Goose was one of the first corporate aircraft. Early sales were to wealthy businessmen, but after the outbreak of the war, the military became a big customer and a total of 345 were built.

Long Island is called “the Cradle of Aviation” not only for famous flights, but for manufacturing. Early manufacturers were small independent entrepreneurs. As World War Two approached, large aircraft companies established on Long Island, most notably Republic and Grumman. These two companies- Republic, in Farmingdale, and Grumman, in Bethpage, continued manufacturing well into the jet age.

This Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat was built in Bethpage in 1945. At the height of Hellcat production, Grumman turned out a record 644 in one month.

Displayed above the Hellcat is an F4F Wildcat, one of the first in the successful line of Navy fighters from Grumman. First flown in 1937, the Wildcat was powered by the Pratt and Whitney R-1830 (which also powered the DC-3). As F6F production ramped up, the F4F was still needed and Grumman, like other manufacturers, outsourced the work, and F4F production was turned over to the Eastern Aircraft Division of General Motors. The Wildcats built by General Motors were essentially the same aircraft, with some upgrades, and were designated the FM-1. Later upgrades, including a switch to the more powerful Wright R-1820 engine, resulted in the designation FM-2.

The Wildcat on display here, an F4F-3, is an early model that was built by Grumman on Long Island. It is the original design, which did not have folding wings. The F4F was one of the most capable fighters during the early part of WW 2 and it continued to serve throughout the war, eventually assigned to smaller aircraft carriers. It was the only Navy fighter to be produced throughout the war.

This Republic P-47N was built in Farmingdale in 1945. The P-47 was the most widely used fighter during World War Two, operating in all theaters of the war.

Near the P-47 is this dramatic model of the Republic factory during WW2, giving the feel of how large and busy these facilities were.

The P-47 is displayed on a section of Marston Matting, one of the many inventions that helped win WW 2. Rolls of this product could be quickly laid out to produce a landing strip in a very short time. Used extensively in the Pacific, a 5,000’ runway could be built in as little as two days by a small team of engineers.

Also displayed next to the P-47 is a cut-away Pratt and Whitney R-2800 radial engine, the 2300 horsepower engine that made the P-47 so fast and successful. The R-2800 was used in over 30 different aircraft including the Grumman F6F Hellcat, the Martin B-26 Marauder, and the Vaught F4U Corsair. It was also successfully used in various airliners including the Martin 404 and the Convair 440 series. The Navy was still flying the R-2800 powered C-118D (DC-6) well into the 1980s. I flew the C-118 in a Navy Reserve Squadron in the 80s and we regularly flew to Europe on two-week detachments. The R-2800 (water injection version) was always very reliable. While my father was serving in the U.S. Air Force, I crossed the Atlantic several times in an Military Air Transport Service (MATS) C-118. I’m sure that my love of aviation came from these flights and they could have been on the same aircraft, as the Navy inherited the planes from MATS.

The history of the Republic F-84 goes back to 1946 when the Thunderjet, the original straight-wing version, made its first flight. It had inferior performance to the North American F-86, and a swept wing version of the F-84 was quickly put into development. The straight-wing F-84 was the first fighter to be capable of air re-fueling and was flown in combat during the Korean War. This plane on display is a P-84B, built in 1947 (after the formation of the Air Force in 1947, the pursuit designation was changed to fighter and all P-84s became F-84s). This was the eighth B model built and it is the oldest surviving example. Although the B models served in active squadrons, later models were vastly superior. This particular plane was recovered from Navy China Lake where it had been used as a ground target.

The designations of the F-84 family can be confusing. The straight wing version was still being produced while the swept wing version was coming on line. The production version of the swept wing was designated the F-84F, while the final straight-wing version was the F-84G. To add to the confusion, a turboprop version, the F-84H Thunderscreech, was built. The propeller blades of the turboprop were designed to be supersonic at the tips, even at idle, making it probably the noisiest plane ever produced. Only two examples of the F-84H were built, and it never went into production.

The F-84 is in the Jet Age section of the Main Galleries (to the right as you enter the museum). There is also a Jet Gallery (to the left) containing an A-10, an A-6, an F-14, and a 707 flight deck.

The A-10 from Fairchild Republic and the A-6 from Northrop Grumman are perhaps the most recognizable jet aircraft from these two Long Island manufacturers. Each is also one of the most enduring aircraft, both having served for well over 40 years. It is fitting that they are displayed together in the Jet Gallery.

The A-10 first flew in 1972 and entered service in 1977. It is still serving today, 45 years later.

Built in 1977, this particular A-10 was assigned to the 45th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Grissom AFB, Indiana from 1982 to 1992. My brother Mike, who is also my editor, was flying out of Grissom at the time and flew this plane. I asked him to tell us a little about the A-10.

“The A-10 could well be the winner of the award for an aircraft that met or exceeded its military requirements, builder’s promises, and pilots’ expectations. It was built to keep Soviet tanks from making it through the Fulda Gap in Germany at the start of WW III. Perhaps its mere presence made that unnecessary, and it went on to excel in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Bosnia. In addition to being an awesome weapon of war, it was an absolute pleasure to fly. In my opinion, Fairchild got everything right. I flew it for 2,000 hours, with only the most minor squawks. They have been talking about retiring it ever since 1983 when I first flew it, but it is still in the thick of battle today.

The most often heard criticism, its lack of speed, is due to the Air Force’s insistence that it be cheap (the engines are off-the-shelf items used on the Navy S-3 and the Canadair Regional Jet), and have an effective high-low-high combat radius greater than the F-4 and F-16. That was not a major problem as pure speed is not necessary for the A-10 mission. The “Hog” will carry 16,000 pounds worth of any weapon in the inventory, plus 1200 rounds of 30mm ammo for its 4,000-pound GAU-8 Gatling gun, stay airborne in combat for 3 hours, and can air refuel. The GAU-8 is an incredibly powerful gun (the recoil is greater than the thrust of one engine), extremely reliable, and will destroy anything the pilot is able to see.

The desert wars proved that it could, indeed, make it home with battle damage resembling a WWII B-17, as Fairchild had promised. It is now equipped with all the current “magic” electronics to work alongside the newest combat aircraft, far exceeding its original design goal as a day, good weather attack aircraft. It will go down in history as one of the great combat airplanes of all time”.

Thanks Mike!

First flown in 1959, and in service until 2019 (the EA-6B version), The Grumman A-6 was one of the navy’s longest serving fighters.

This Grumman A6-F Intruder was built in Calverton, Long Island, in 1987. It is one of just three pre-production prototypes of the F model. It had more powerful engines (the G.E. F 404 engine, as used in the F-18), new radars, and digital avionics. This aircraft was flown for a total of just 2 1/2 hours before the program was canceled.

As mentioned earlier, one of the founders of the museum worked for Pan American and the third floor of this large museum has a gallery devoted to the history of Pan Am. Many panels and cases of memorabilia as well as aircraft models illustrate the history of this famous and historic airline. Continuing the theme of the museum, Pan Am founder, Juan Trippe, grew up in Manhattan. In 1909, at age 11, he attended an air show on Long Island. That show included a race around the Statue of Liberty, which was won by Wilbur Wright. Trippe’s early interest in the future of aviation was most certainly influenced by that experience. Trippe learned to fly on Long Island (in a Jenny) after joining the Marine Corps during WW1. His first foray into the airline industry was the founding of Long Island Airways. The airline was short-lived, but he was hooked on the future of airlines.

Perhaps the most interesting period in Pan Am’s history was the period before World War 2, when the airline was flying the huge Clipper Ships and developing air routes throughout the world, most notably across the vast Pacific Ocean.

The classic Boeing 307 and the Martin M-130 Clippers are remembered with various displays and photographs.

Although there are no aircraft in the Pan Am gallery, the nearby Jet Gallery has the nose of a Boeing 707, the aircraft which Pan Am used to introduce passenger jet service (in 1958) on the North Atlantic.

This 707 nose is from the first jet purchased by the Israeli airline, El Al. Beginning in 1961, it flew twice weekly between New York and Tel Aviv. This aircraft established two records. At 5760 miles, it was the longest non-stop commercial flight and it set a speed record of 9 hours 33 minutes between the two cities.

This 707 was in service for 23 years and it is displayed in the condition it was in when it retired in 1984. Visitors are treated to a look at the cockpit representing the early years of jet airliners- a three-person cockpit, with all traditional round gauges and manual systems for the flight engineer. It is a far cry from the two-person glass cockpits with automated systems of today’s airliners.

Guiseppi (GM) Bellanca earned an engineering degree in Italy and made an (unsuccessful) attempt at building an airplane in Milan. He saw greater opportunity in the U.S. and emigrated here in 1911. He immediately began work on a plane in his basement in Brooklyn. Within six months, he had successfully flown his plane (on Long Island) and, in the process, taught himself to fly. By 1913, he had established a successful flying school in Mineola.

This replica was originally built as a flying replica, with a modern engine. After acquisition by the museum, it was restored and the modern engine was replaced by a replica of the original Anzani engine.

For more about the history of Bellanca see issue 27 about the Bellanca Airfield Museum.

Photo courtesy of CAM

To finish this issue, let’s return to the story of Harriet Quimby. Harriet was the daughter of a poor farmer from Michigan, and her family moved steadily westward in search of a better life. They eventually settled in California and, through the will of Harriet’s strong mother, their fortunes turned better. After finishing college, Harriet planned on becoming an actress, but had limited success. She found an opportunity, however, to supplement her income by writing about theater and film and she eventually became a successful and well-known journalist. Harriet moved to New York and travelled the world writing magazine articles. In 1910, she covered the International Aviation Tournament on Long Island. The week-long meet, just seven years after the Wright Brothers first flew, illustrates how the Long Island area had become “the cradle” of early aviation. There were 75,000 paid attendees, but it was estimated that over a million people watched the events from the streets and from roof tops. Notable attendees were the Wright Brothers (who did not allow their planes to compete, because of bad weather), former President Teddy Roosevelt, and many of the nation’s elite names such as Vanderbilt and Drexel. The final event was a race to the Statue of Liberty and back and the winner (although he was later disqualified) was John Moisant, flying a Blériot XI. Harriet Quimby became enamored with flying (she had already set a women’s speed record in an automobile) as well as with Moisant. She soon began lessons at his flying school, which led to her receiving the first pilot license awarded to a woman.

While continuing to write for major magazines, Harriet joined Moisant’s flying circus, the Moisant International Aviators, and participated in air shows throughout the U.S. After ordering her own Blériot, Quimby went to England and achieved her goal of being the first female to fly the English Chanel.

On July 1 1912, Harriet flew in the Third Annual Boston Aviation Meet at Squantum, Massachusetts. Her brand new Blériot XI was a two-seater and she took meet organizer Bill Willard along as a passenger on a demonstration flight. Willard was a large man and the two-seat Blériot had already exhibited stability issues. For some reason, Willard shifted position in his seat (seat belts were not yet widely installed in aircraft) and he was ejected from the plane. The change in weight and balance upset the craft and Harriet, too, was ejected from the plane. The tragic accident led to an increased use of seat belts in planes.

Standing next to the Blériot on display here as well as the Vin Fiz replica, we are able to get an appreciation of the fragility of these early planes and the challenges that faced the brave early aviators who flew them. Harriet Quimby’s flying career was short, but she accomplished much and left a legacy of determination, especially for woman pilots.

-----------------------------------------------

The main purpose of this blog is to give exposure to all the great aviation museums and to encourage readers to visit them. I always recommend visiting the museums that I write about, but The Cradle of Aviation Museum is truly one you shouldn’t miss. There is much more to see!

---------------------------------------------

A special thanks to museum Curator, Josh Stoff, as well as docent Bob Goldstein for their assistance with my research. Thanks also to Bob for giving me a tour at the museum as well as the many great and knowledgeable docents I spoke with while I was there.

-----------------------------------------------

—————————————————————-

To learn about what to do in the local area, museum hours and costs as well as books to read and other interesting odds and ends, keep reading! At the end you will find a photo gallery of the entire museum.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

Museum Hours-

Tuesday-Sunday

10:00 am - 5:00 pm

Adults $16, Child/Senior $14

Note- The planetarium is closed for renovations and will re-open with an all-new state-of-the-art laser projection system.

FLYING IN

Republic Airport is 15 miles away- to the east, away from LaGuardia and Kennedy. There is also a great museum on Republic Airport, American Airpower Museum, the subject of an upcoming blog.

LOCAL ATTRACTIONS

The Museum is located in a complex which also contains a Firefighting Museum, an operating vintage carousel, and a children’s museum, making it an excellent destination for adults and children.

WHERE TO EAT

The museum has a large café behind the planetarium.

SUGGESTED READING

Museum docent Bob Goldstein recommended Fearless- Harriet Quimby-a life without limit by Don Dahler and it turned out to be a great read. Harriet Quimby had a short but amazing life and Dahler does an excellent job bringing it to life. The book not only tells the story of Harriet Quimby, but the background events of the time both in aviation and other world events.

MUSEUM WEBSITE

https://www.cradleofaviation.org/

UP NEXT

Hiller Aviation Museum, San Carlos CA

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

This Grumman F-11 Tiger sat in a park in New Bern, NC for 37 years. The Naval Aviation Museum, which owns the aircraft, made a site inspection in 2009. Due to the deteriorated state of the plane, the Navy said it would have to be restored, or returned to the Navy Museum.

The city, along with private companies, decided to undertake the expense of the restoration. The F-11 served as the Blue Angels demonstration aircraft from 1957 to 1969 and the restoration team at MCAS Cherry Point painted the Tiger in Blue Angels livery. It was then placed on a pedestal in its current location in Lawson Creek Park.

PHOTO GALLERY

Click on any image to enlarge

Issue 37, Copyright©2022, Pilot House Publishing, LLC. all rights reserved. Except where noted, all photos by the author