The Franklin Institute

Issue 51, A visit to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia Pa February, 2025

The Wright Brothers made the first successful heavier-than-air, powered flight, on 17 December 1903, in Kitty Hawk North Carolina. They returned to their home in Dayton Ohio in time for Christmas and immediately began searching for a location to continue their experiments. They found a large field, Huffman Prairie, that they could use, and they built a new larger and stronger craft with a more powerful motor to continue their testing.

On 5 October 1905, after two years of testing and tinkering, Wilbur flew 24 miles in 38 minutes, making 29 laps around Huffman Prairie- only landing when the fuel ran out. This flight, seen by a dozen family members and friends, made the brothers feel that they had now truly invented flight and they decided it was finally time to put their invention on the market. They did not fly at all in 1906 or 1907, concentrating on getting a military contract both in the US and in Europe- and building more planes. During this time, they came close to various contracts but the sticking point was always that they would not give a demonstration flight until a contract was signed. They maintained their concern that their control system, which is what they got the patent for (in 1906), would be stolen.

In early 1908, the Wright brothers returned to Kitty Hawk for some testing and to brush up their flying skills. By the end of that year, Wilbur was in Europe participating in flying demonstrations and Orville was in Virginia to vie for a US Army contract. Both were successful and the Wright brothers finally became world famous.

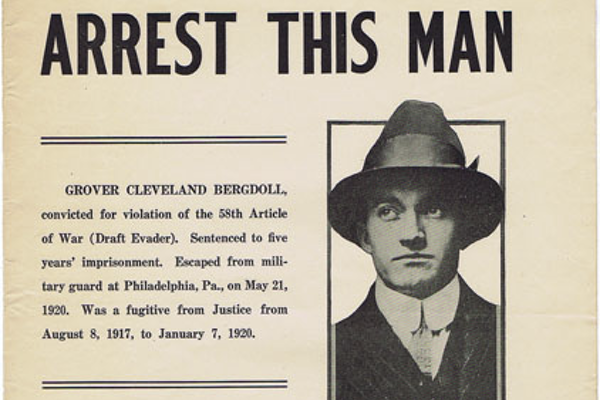

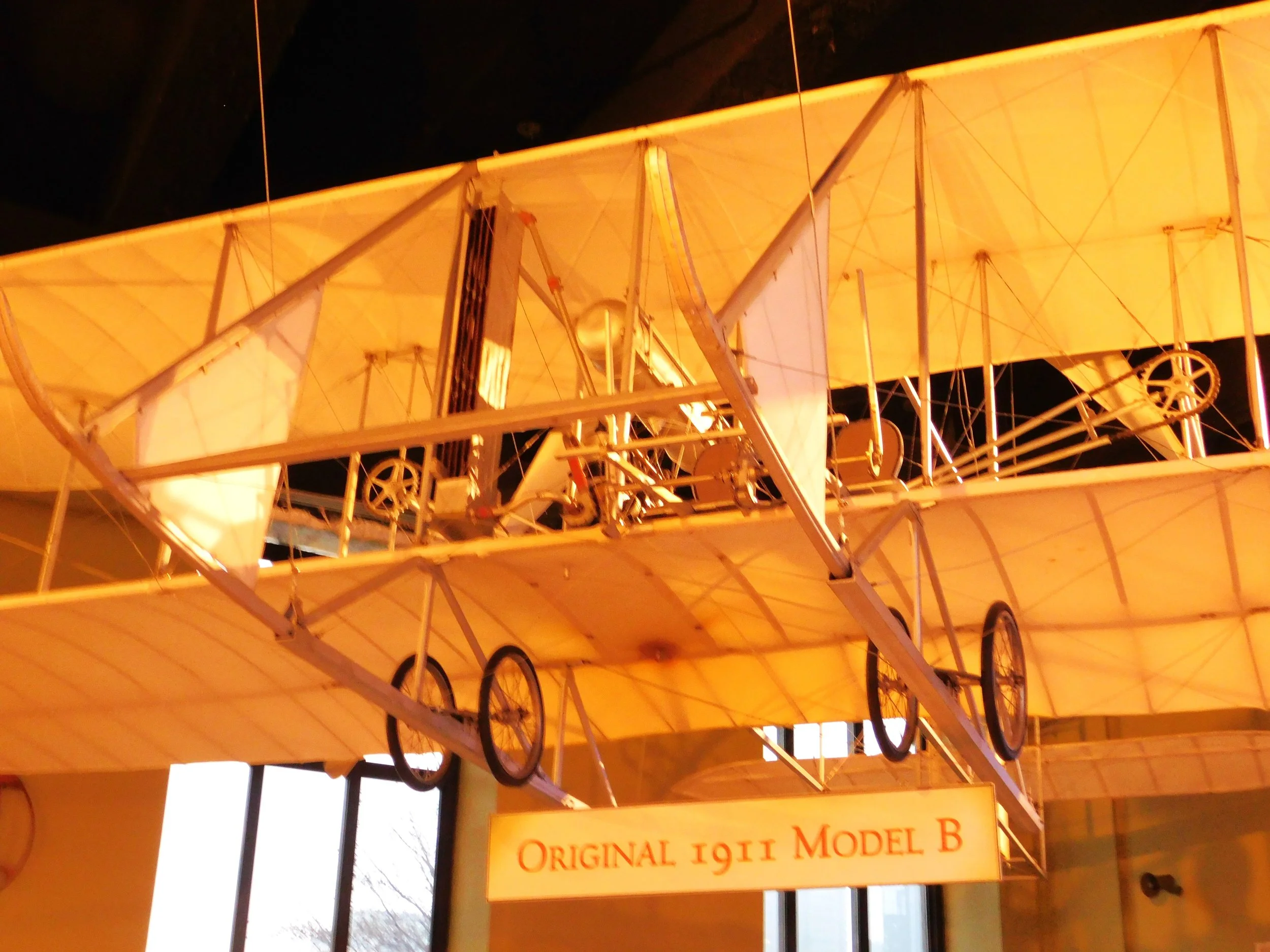

In the next few years, the Wright brothers sold many planes, including some to private owners. One such sale, in 1912, was to Grover C. Bergdoll, a wealthy Philadelphia playboy. The plane was a Wright Model B, a two-seater, and Orville trained Bergdoll to fly it.

Bergdoll was heir to a brewing fortune and he used his money to drive fast cars and fly his airplane recklessly, earning himself the nickname “Playboy of the Eastern Seaboard”. His fast driving and flying were not appreciated in the Philadelphia area and the hate for Bergdoll came to a head when he evaded the draft for World War I.

Bergdoll was arrested and imprisoned, but he escaped in 1920 and fled to Germany. In 1921, most of his personal property, including his plane, was confiscated by the government. In 1933, a warehouse was discovered containing Bergdoll’s plane and many of his cars. The Wright two-seater was restored and was hung in the Franklin Institute in 1934, where it has been on display ever since. Most Wright aircraft on display in museums, and there are many, are reproductions. This is one of the few original Wright aircraft still existing. There were many Model Bs built between 1910 and 1914, but this is the only known Model B remaining.

——————————————————————————————————-

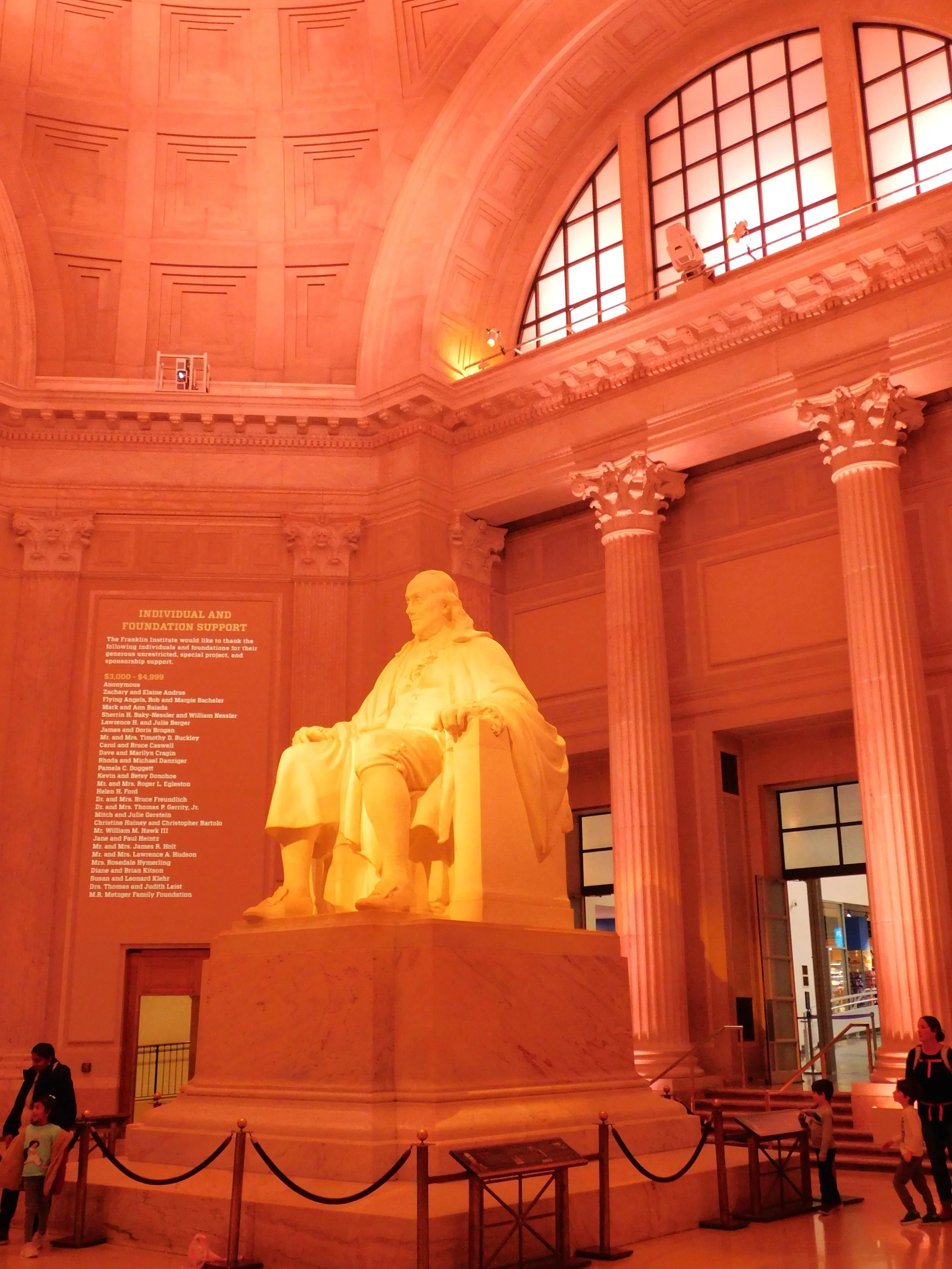

Founded in 1824, the Franklin Institute is a science and technology museum with air and space halls but, of course, much more. From the beginning, the Institute concerned itself with making science more professional and promoting scientific teaching. Construction started on the Institute’s first long-term home in 1825, at 15 S. Seventh Street. The current building, on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, opened in 1934. With this new building, the mission of the Franklin Institute moved more toward bringing science and technology to the general public.

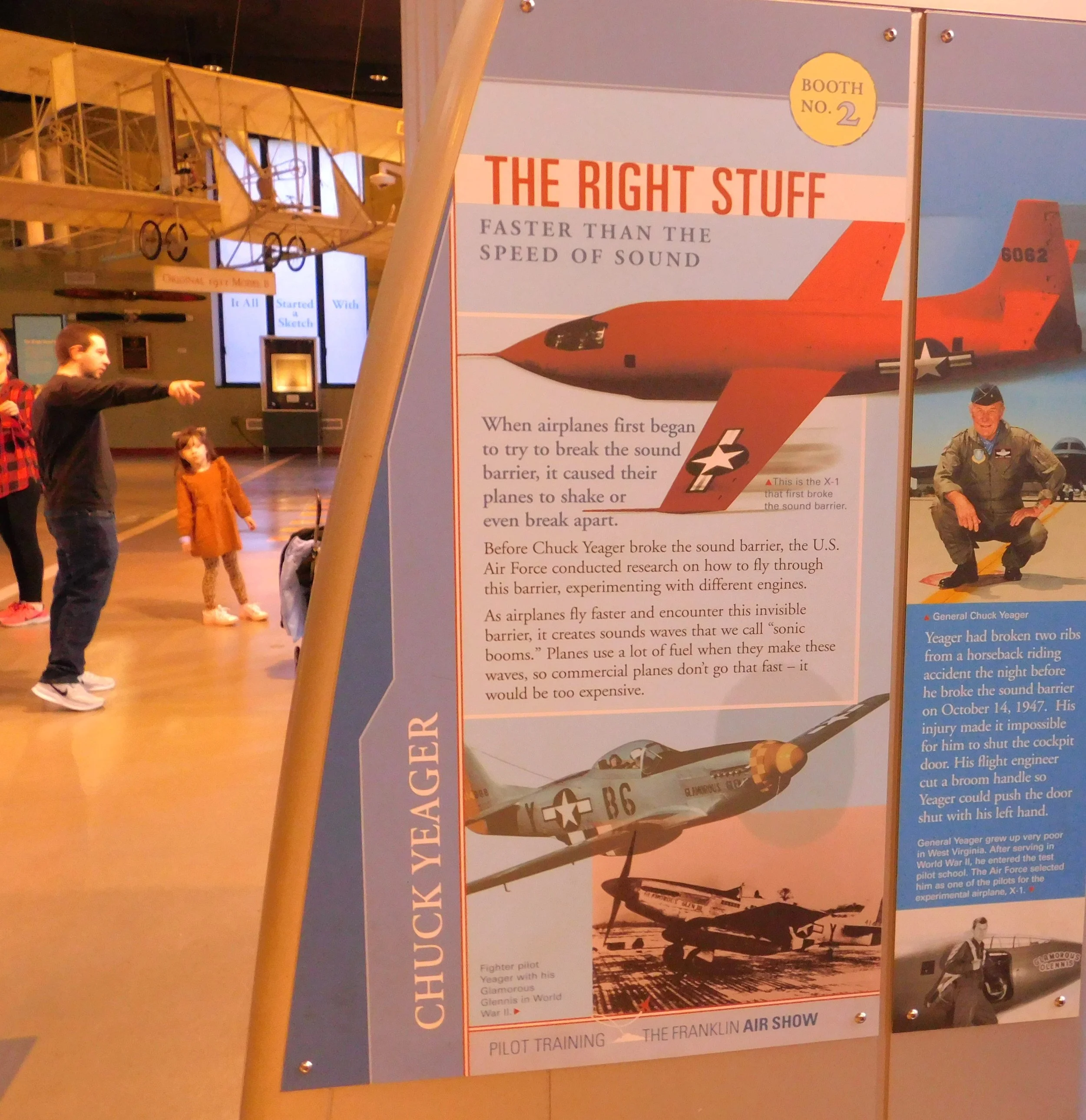

Dominating the Aviation Hall (Franklin Airshow) are two aircraft: Bergdoll’s Wright Flyer and a 1953 Lockheed T-33 (53-6038).

The T-33 was developed from the Lockheed F-80, which was the first operational jet fighter used by the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) in WWII. Designed by Kelly Johnson, the F-80 was built in just 143 days. Just two pre-production models saw action in Italy at the very end of the war. The “Shooting Star” went into full production in 1945 and a total of 1715 were built. The F-80 saw extensive combat during the early part of the Korean War, but the straight-winged fighter was quickly outclassed by newer swept-wing aircraft.

With docile handling characteristics, the F-80 was seen as a practical trainer and, in 1948, a two-seater version was designed. Designated the T-33, the training version was very successful with over 6,500 built, serving well into the 1960s. The T-33 retained the Shooting Star name, although it was more commonly referred to as the T-Bird. The Navy ordered 649 which they first designated the TO-2, then the TV-2 when they changed their designation system (and they joined the rest of the world in 1962, when they named it the T-33).

The T-33 is a very popular attraction as it is open to climb up into. Children and adults alike always enjoy this type of display in a museum.

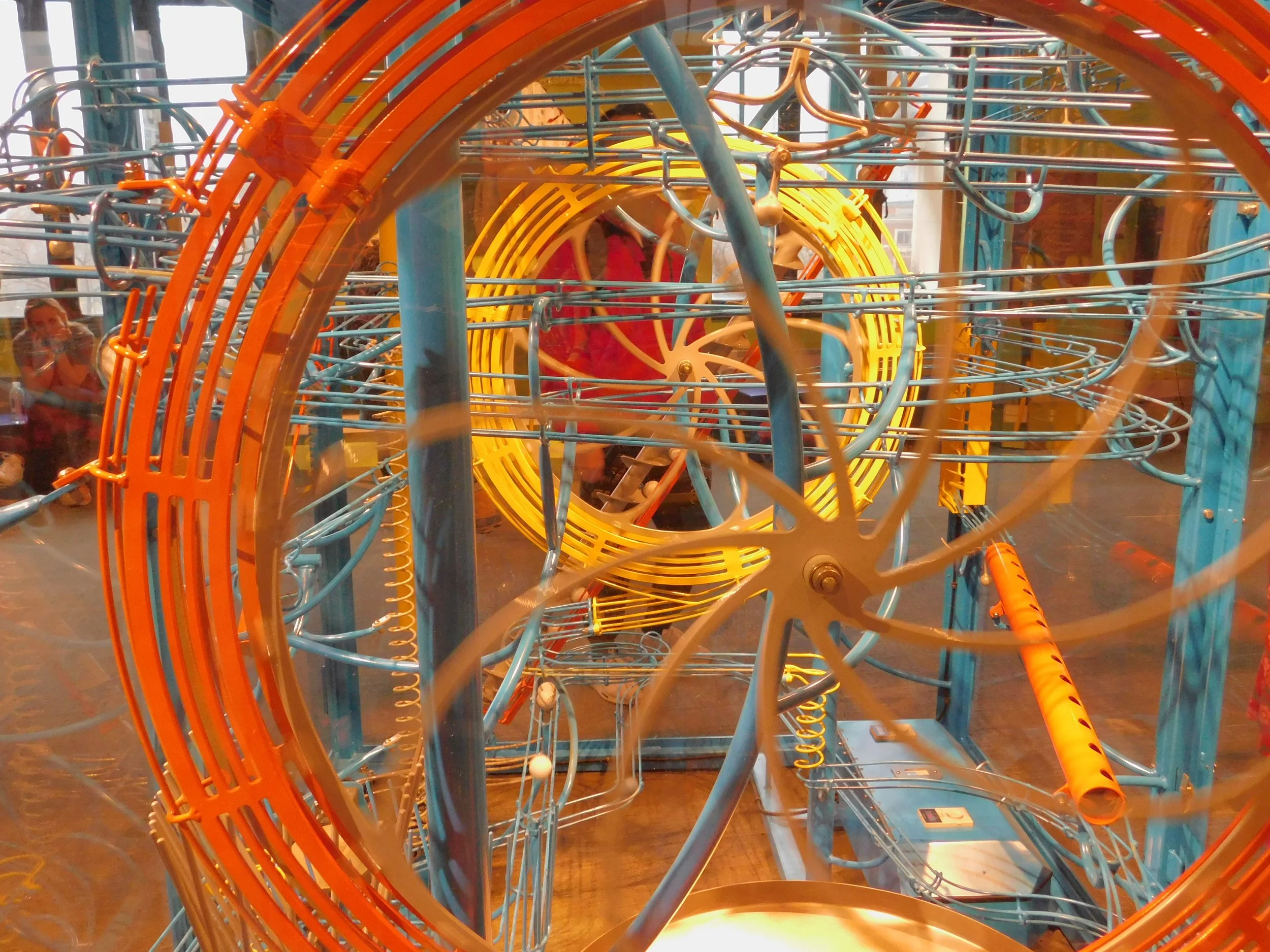

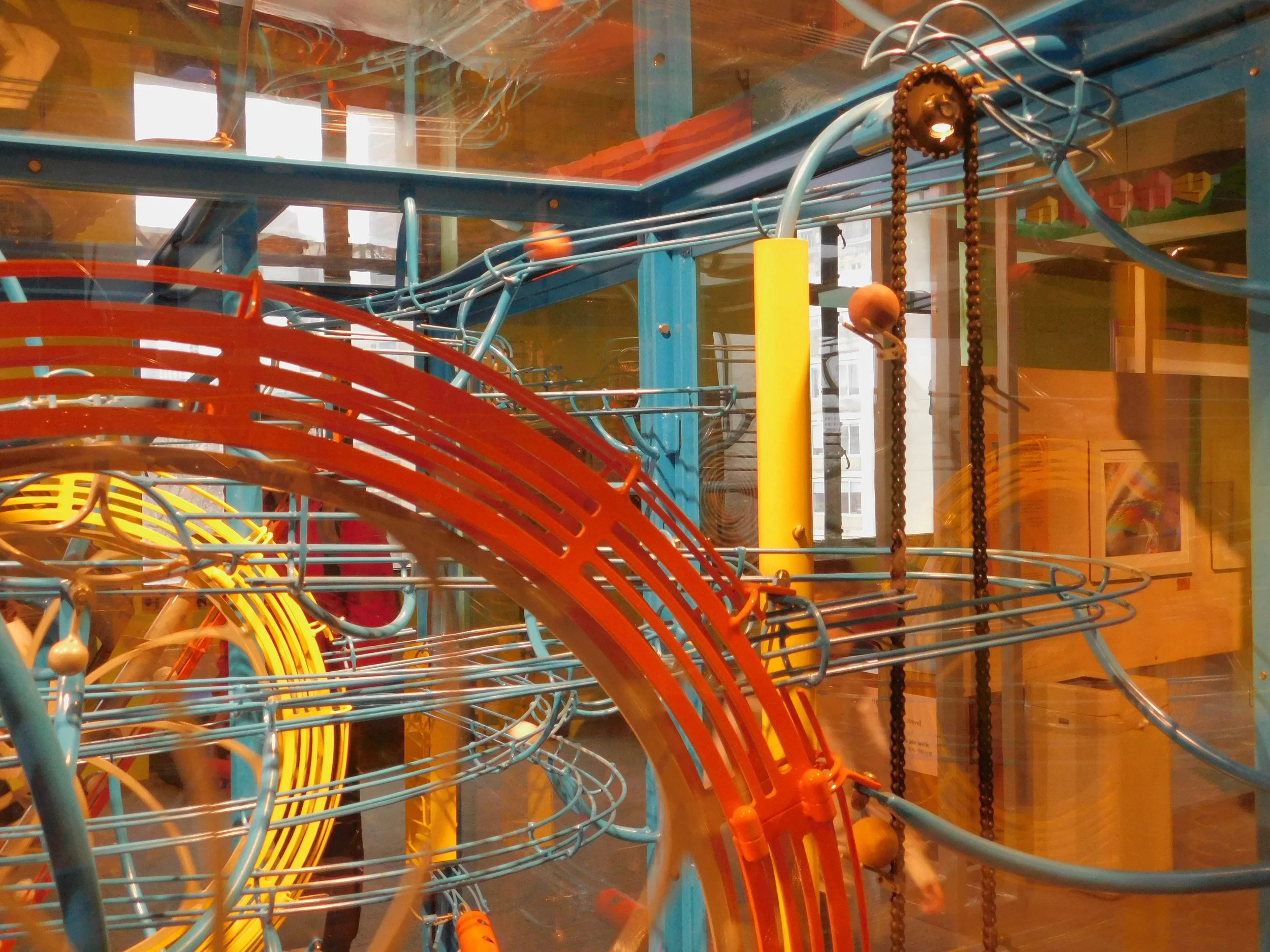

In the spirit of inquiry and discovery embodied by Benjamin Franklin, the mission of the Franklin Institute is to inspire a passion for learning about science and technology. To that end, the museum has numerous interactive displays to interest young visitors.

————————————————————————————————————

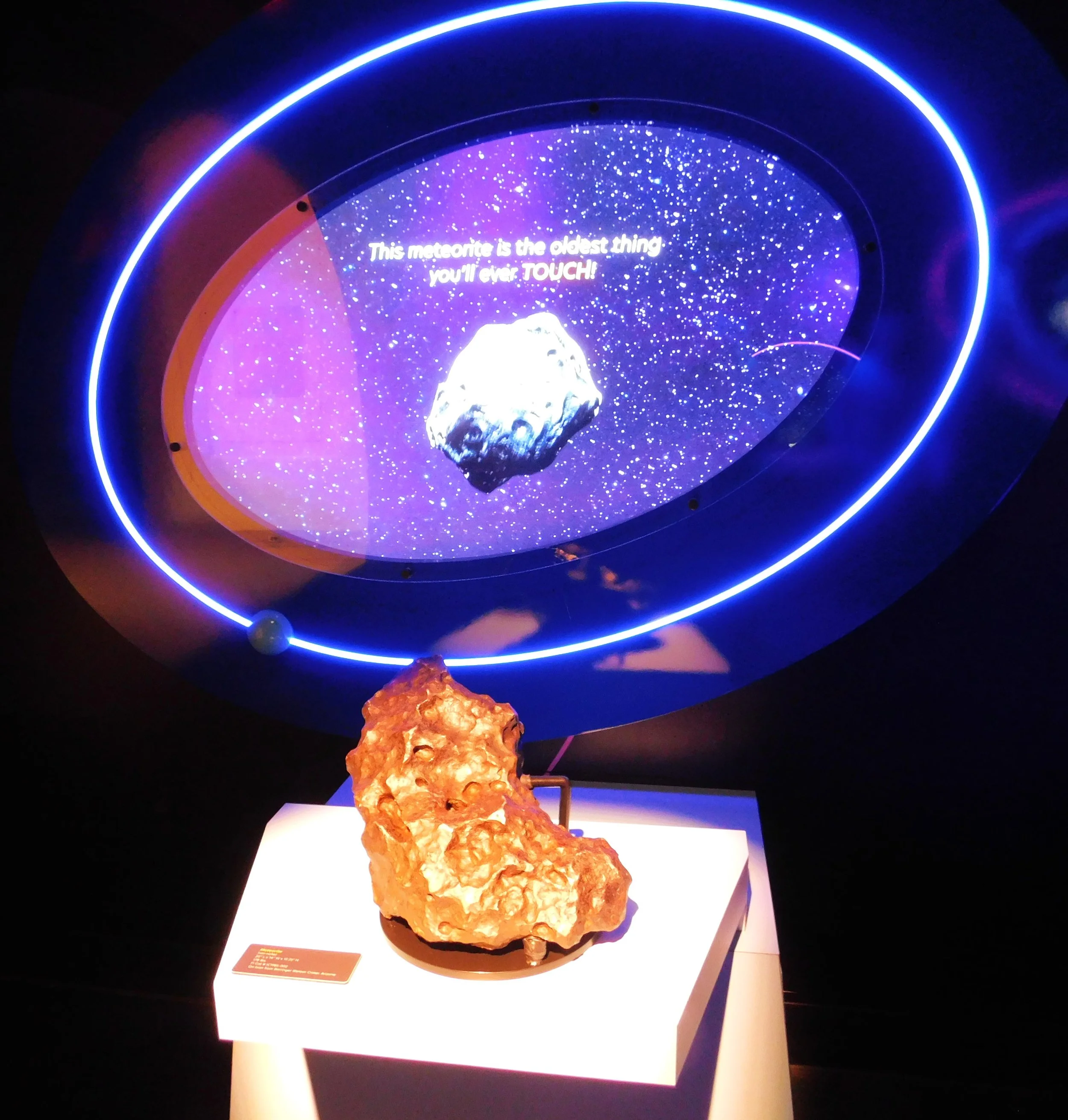

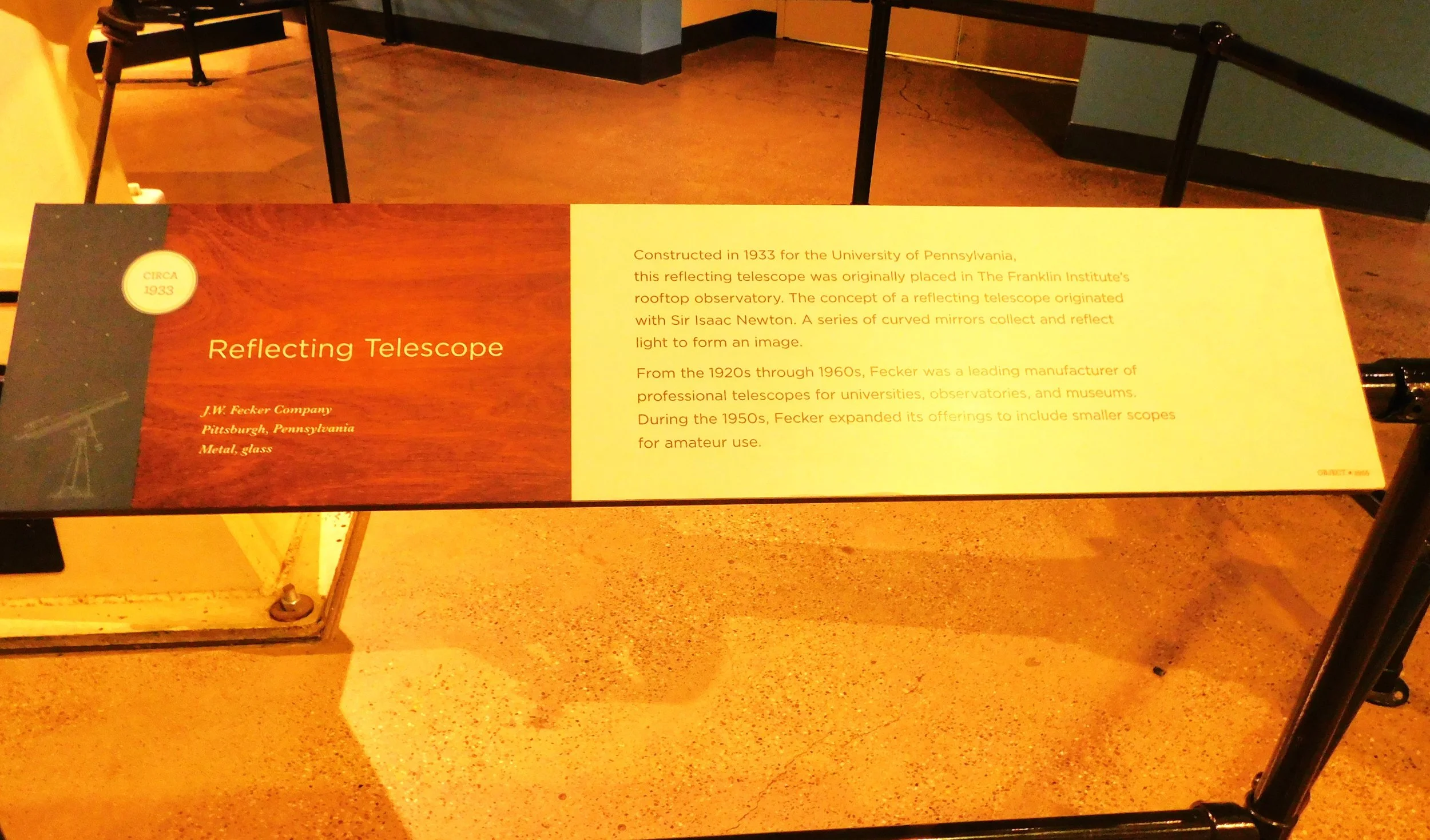

Next to the Franklin Airshow is Wonderous Space. It is a two-story collection of motivational and interactive displays.

Here is how the Franklin Institute website describes Wonderous Space- “Discover what lies beyond Earth on the second floor. Learn about the incredible size and scale of celestial bodies as you travel through the universe. Touch a real meteorite that fell to Earth over 50,000 years ago. How does gravity shape the universe? What affects an asteroid’s impact crater?

On the third floor, imagine yourself in a space career as you experience the engineering it takes to get to space. Design and launch a rocket or see real space technology that could also benefit life on Earth. What do we need to live on Mars? Are there other worlds in our galaxy that could support life?

Whether you’re a space enthusiast, or simply curious about the mysteries of the universe, this exhibit will ignite your imagination and leave you with a deeper appreciation when you look up at the night sky.”

Wonderous Space certainly lives up to its name.

The Franklin Institute has always been near and dear me to as they were responsible for my first two flying lessons. I went to high school at Roman Catholic HS in downtown Philadelphia- walking distance from the Franklin Institute. I had a group of friends who enjoyed going to local museums, but my favorite was always the Franklin Institute. And my favorite area there was the aviation gallery, where they had a WWII era Link Trainer.

Link trainer c1963 Public domain photo

It was the original, very basic, flight simulator that was used extensively during WWII and beyond. It moved left and right with rudder input and the nose went up and down in response to stick inputs. There was a gun-sight on the dash and the wall in front of it had a huge photograph of Philadelphia from the air, with a small circle of light projected onto it. The spot of light moved all around and the idea was to keep this dot of light in your gun-sight. They kept score, and the top score each month won a free flying lesson. You had to be 16 to enter, so as soon as I hit the magic age, some friends and I went to give it a try. I thought I had done OK and sure enough, a few weeks later, I got a letter of congratulations saying I had won an hour flying lesson at Wings Field.

I don’t remember much about the flight other than it was in a Cessna 172 and I really enjoyed it. The contest rules were that if you won, you could not enter again for two years. So, in my senior year, after turning 18, I entered again, and won again. They had reduced the prize to a 30-minute lesson, but it was still fun. I don’t think that these flights were much of an influence on me, because I was already fully committed to flying as a career. But it did show me that I probably had a knack for it.

The Franklin Institute has changed a lot since the 1960s, not in size or purpose, but by upgrades and modernization. The link trainer is no longer on display but three displays that I always associate with a visit to the Franklin Institute are still in place.

One of those exhibits is Foucault’s Pendulum. The experiment was first devised by French physicist Jean-Bernard-Leon Foucault in 1851. The experiment shows how the Earth rotates around its axis. The Earth is spinning and the pendulum is swinging, which creates the interesting effect. The heavy pendulum hangs down from the very top of the museum and pegs are placed in a circle around the base. At 9:30 am, the museum starts the pendulum swinging in a North-South direction. During the day, the pendulum knocks down a peg every 20-25 minutes, making it appear to change direction- the movement is actually caused by the Earth’s rotation. By 5:00 pm, half of the pegs have been knocked down.

Close-up of pendulum and pegs – photo courtesy of the Franklin Institute

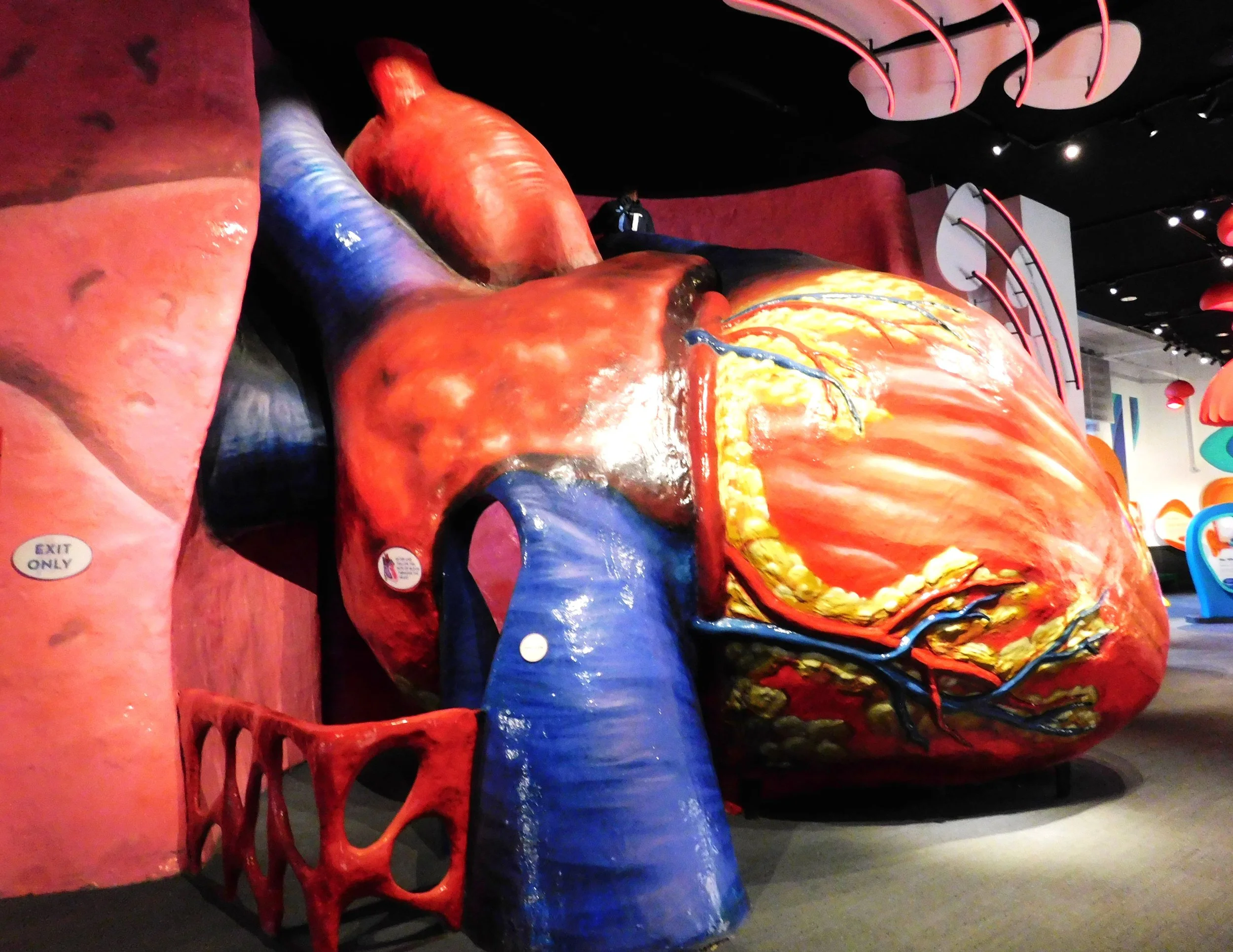

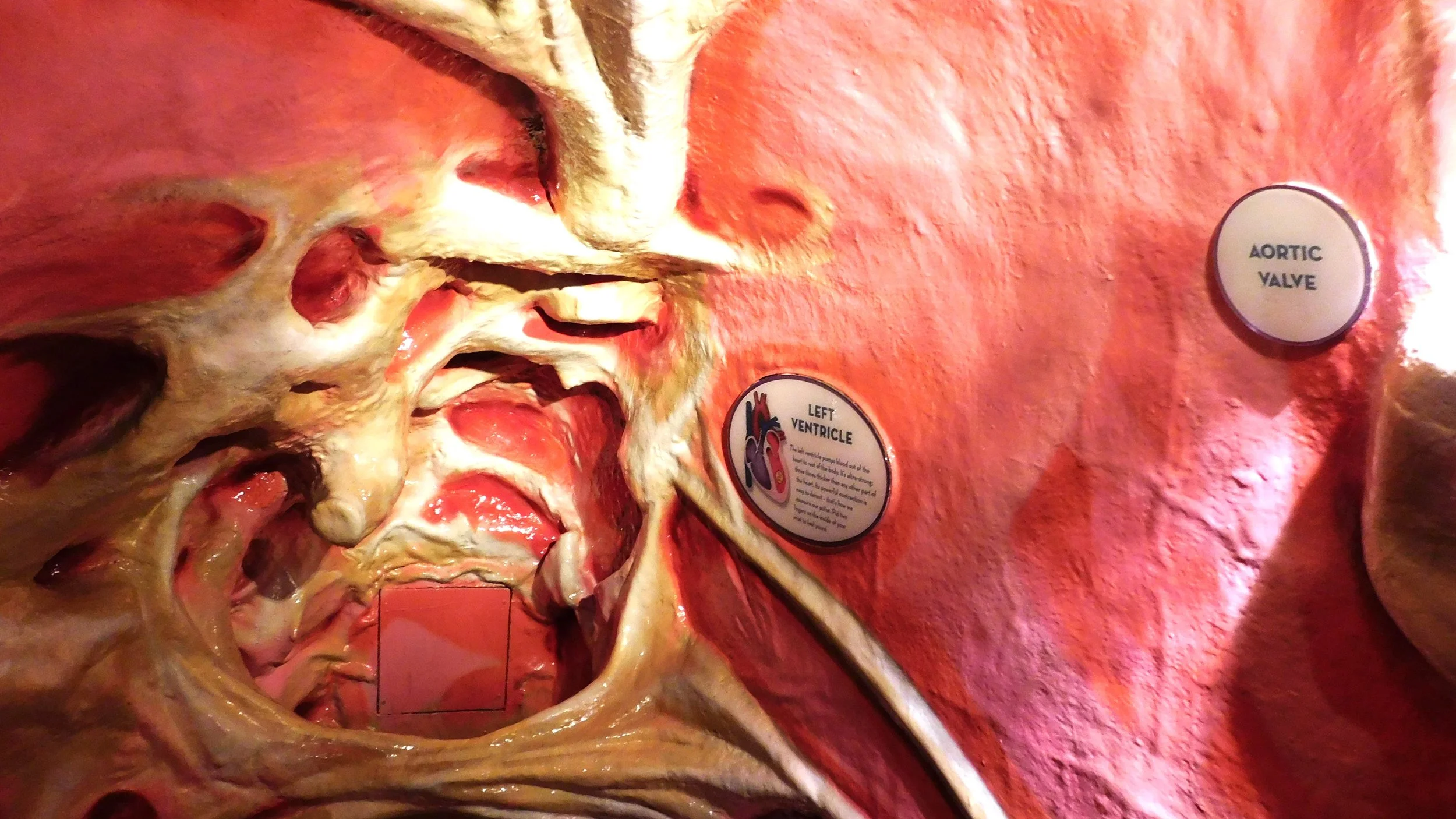

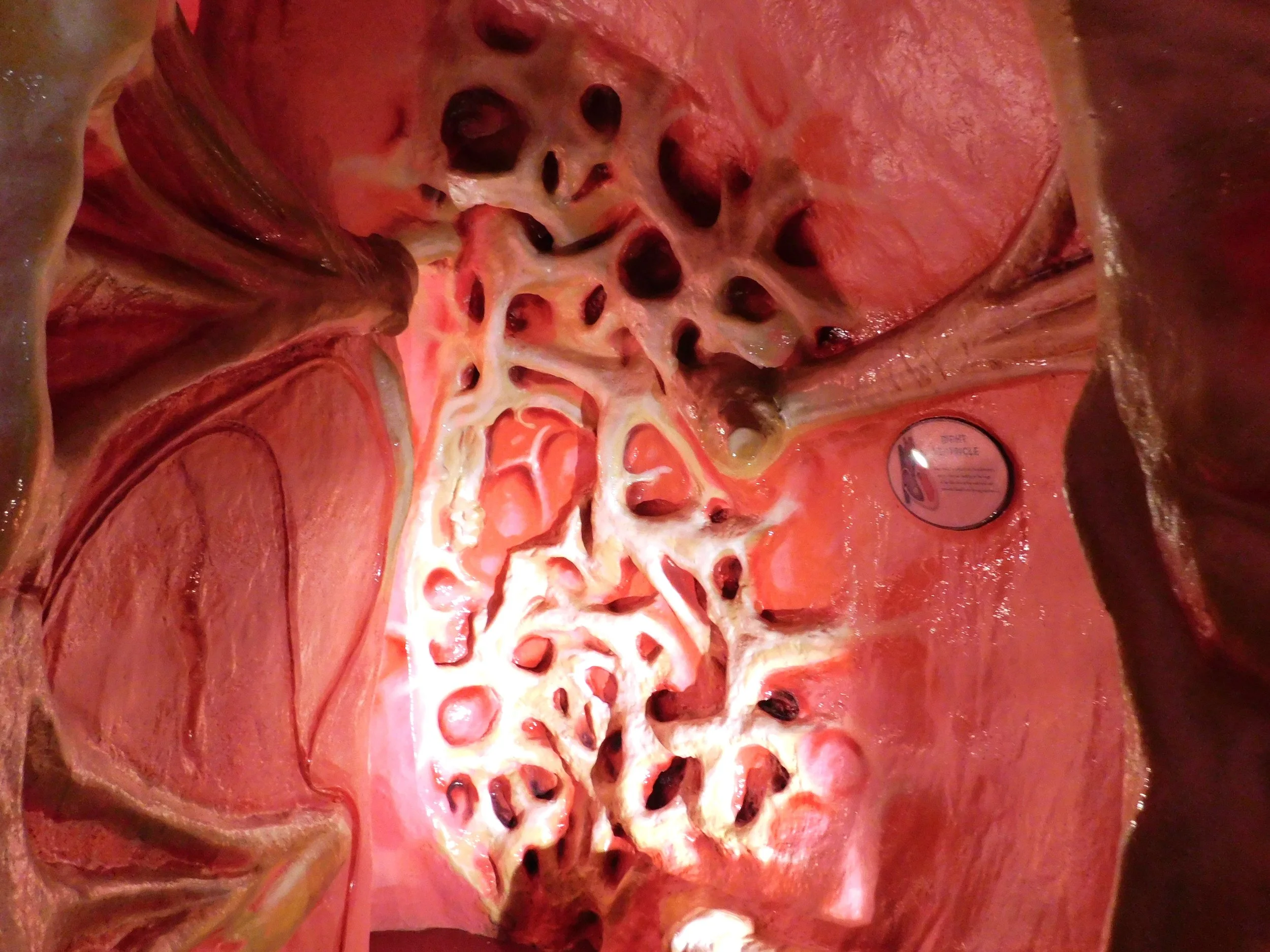

Perhaps the most iconic exhibit in the Franklin Institute is a huge model of the human heart, big enough to walk into.

Visitors enter the heart and follow the path that the blood follows, ending in the lungs. It is a most interesting way to teach the workings of the heart and lungs, and it cannot fail to amaze and teach young and old alike.

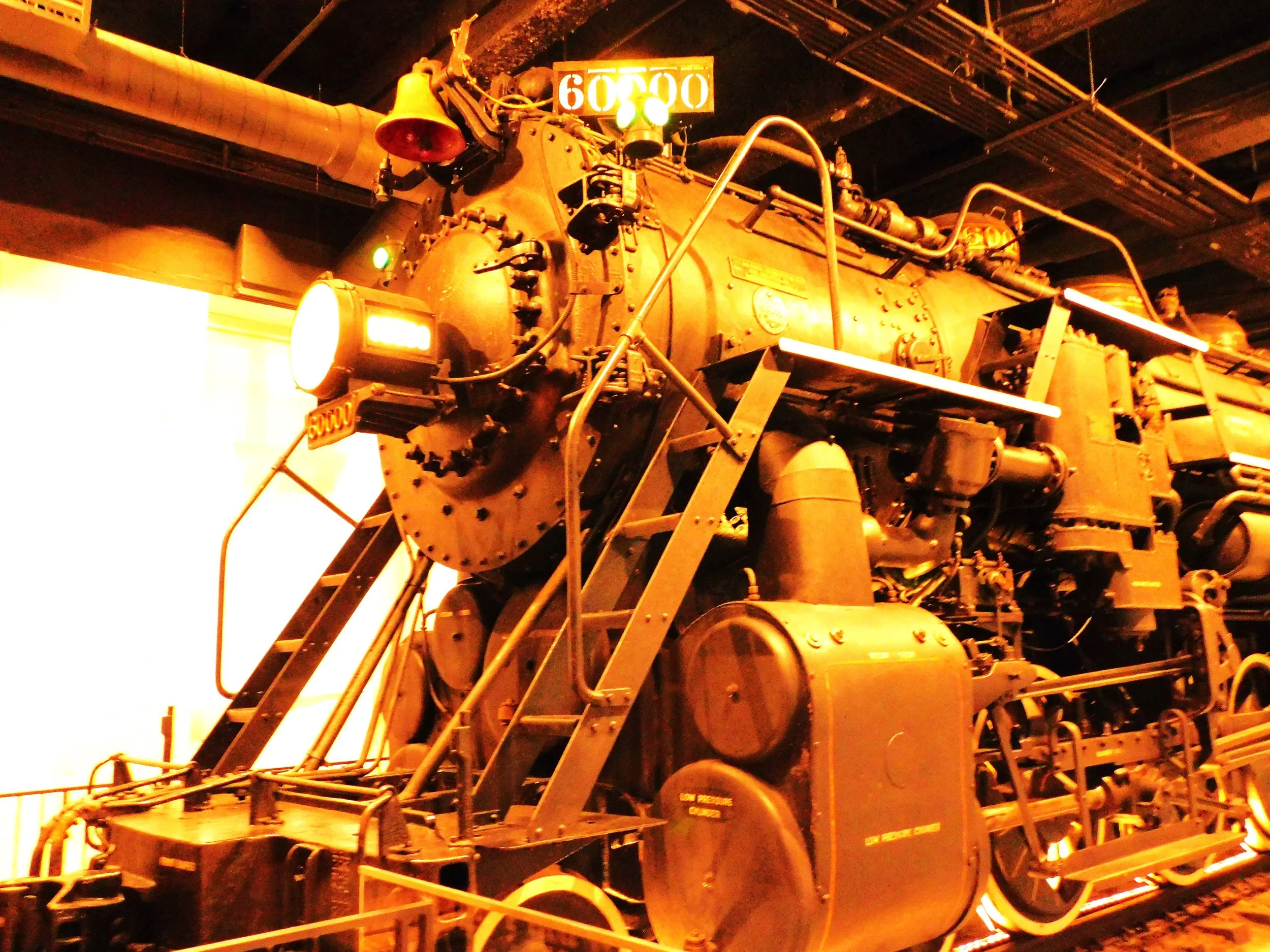

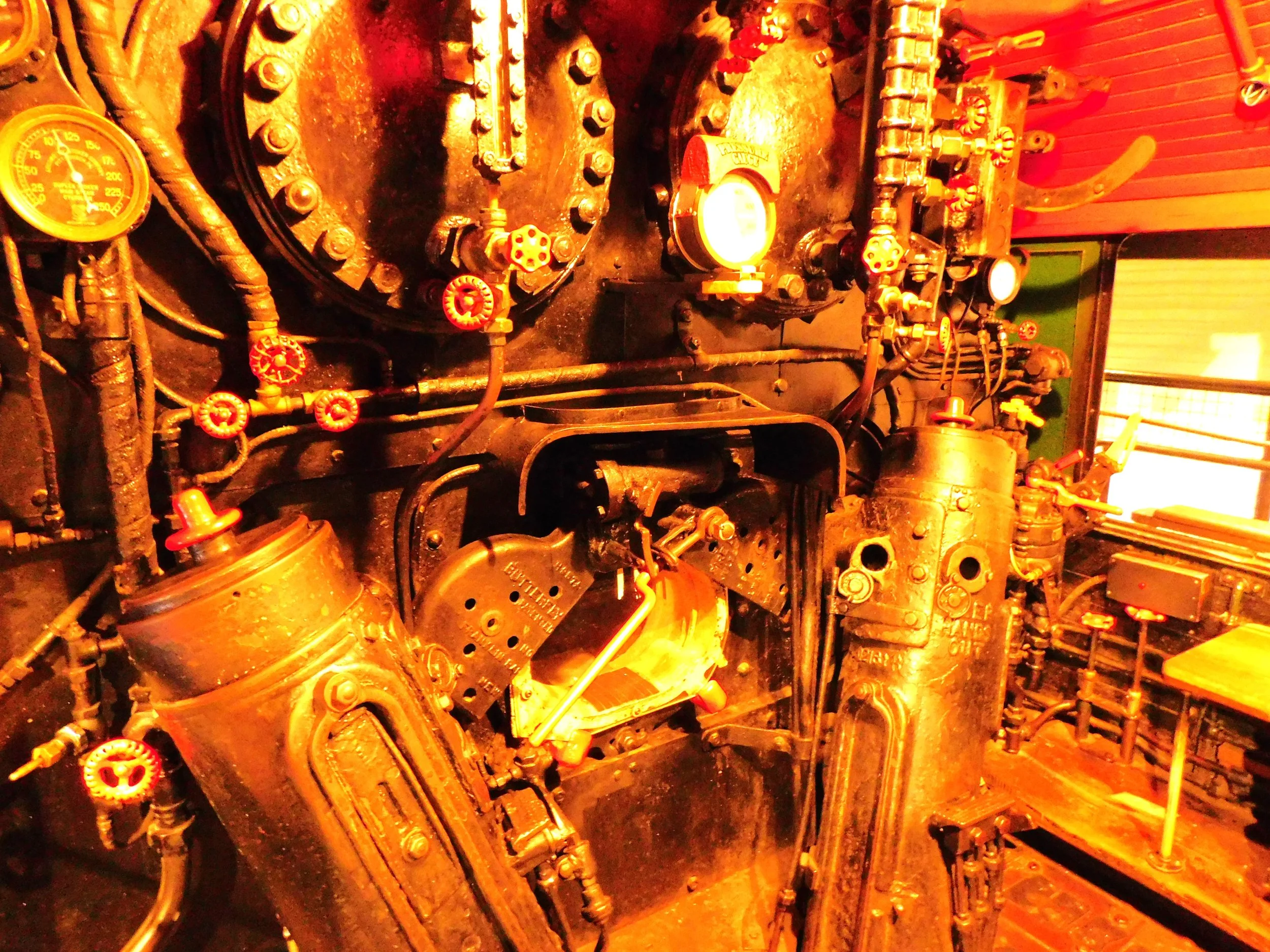

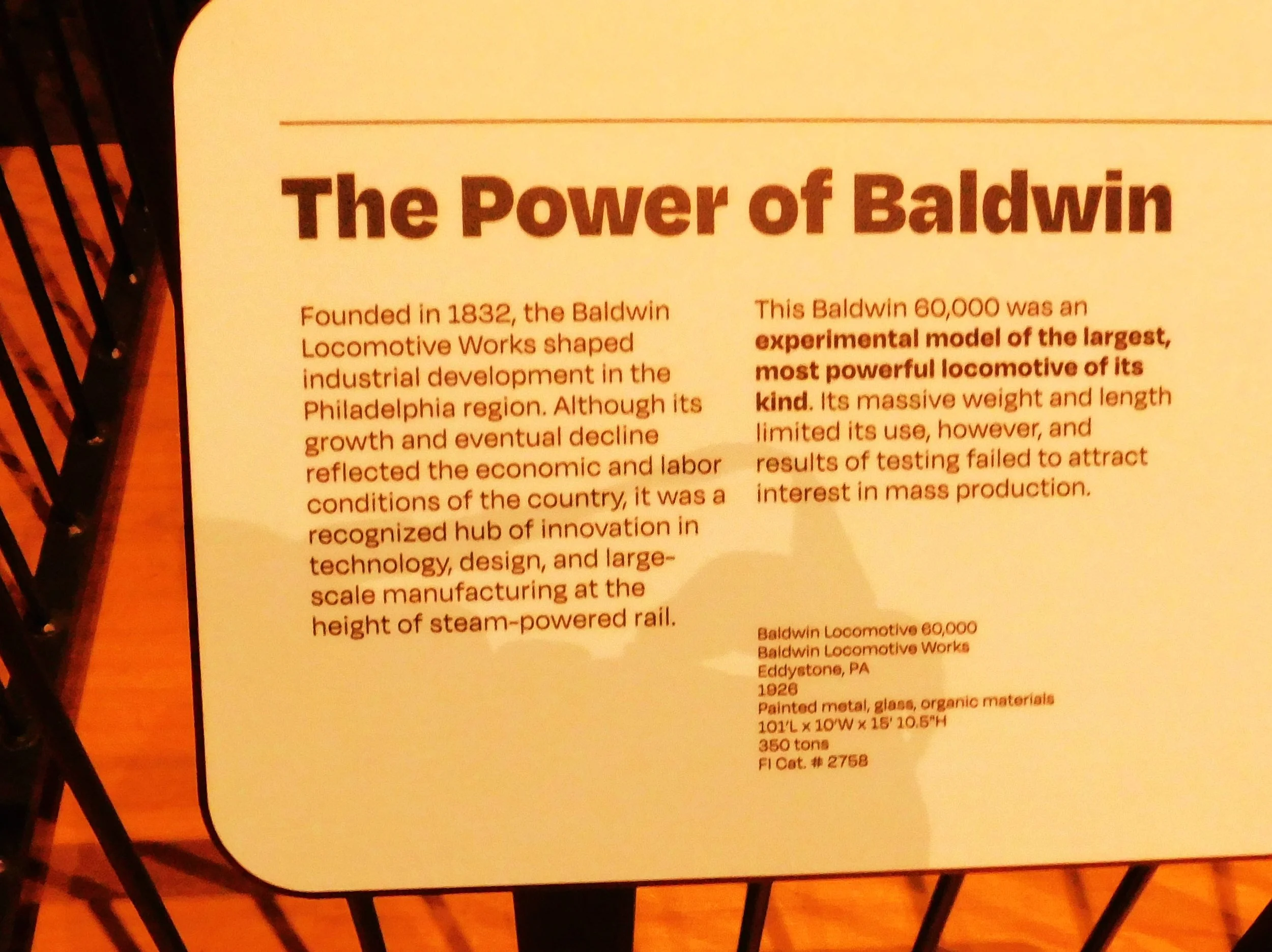

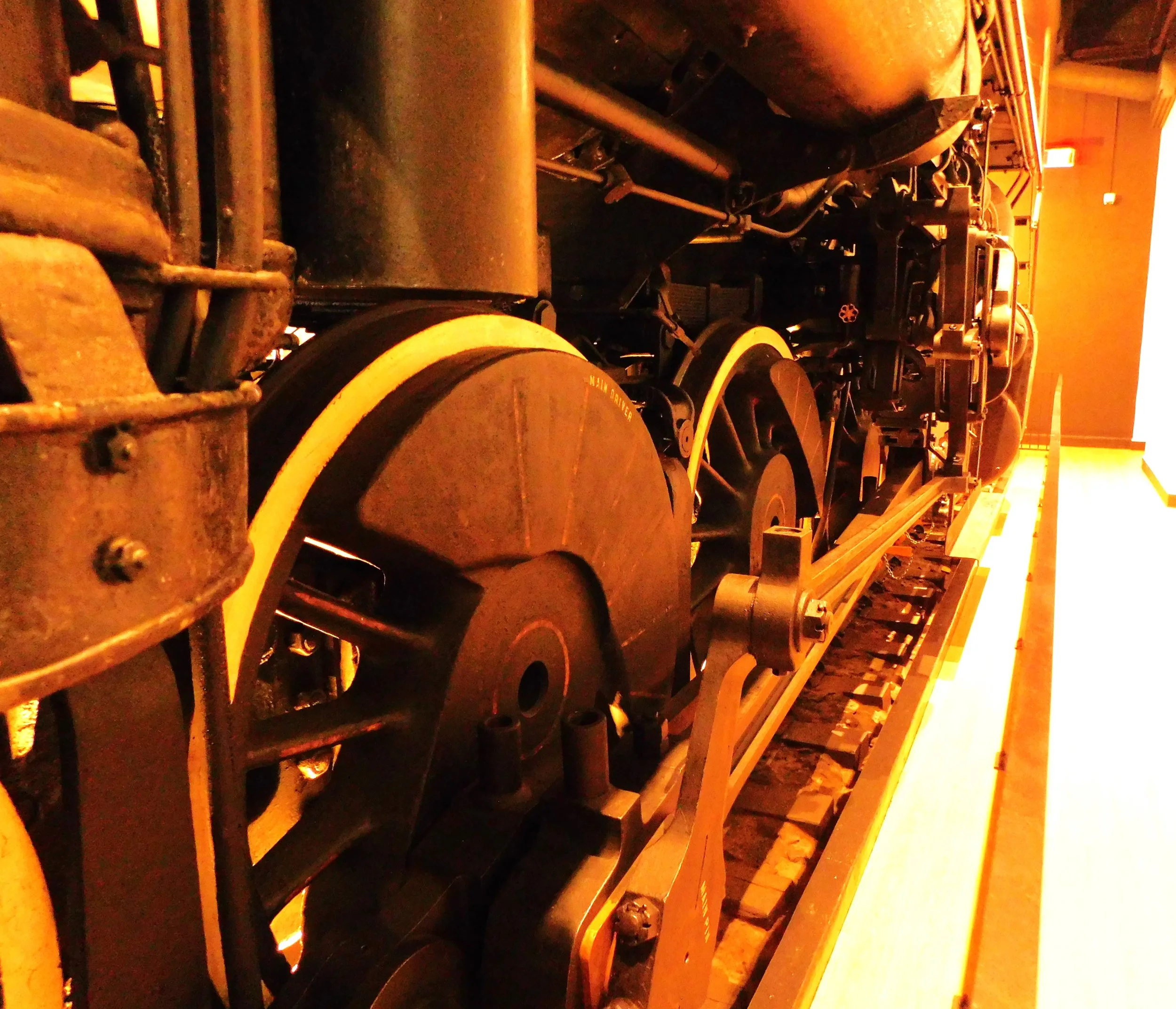

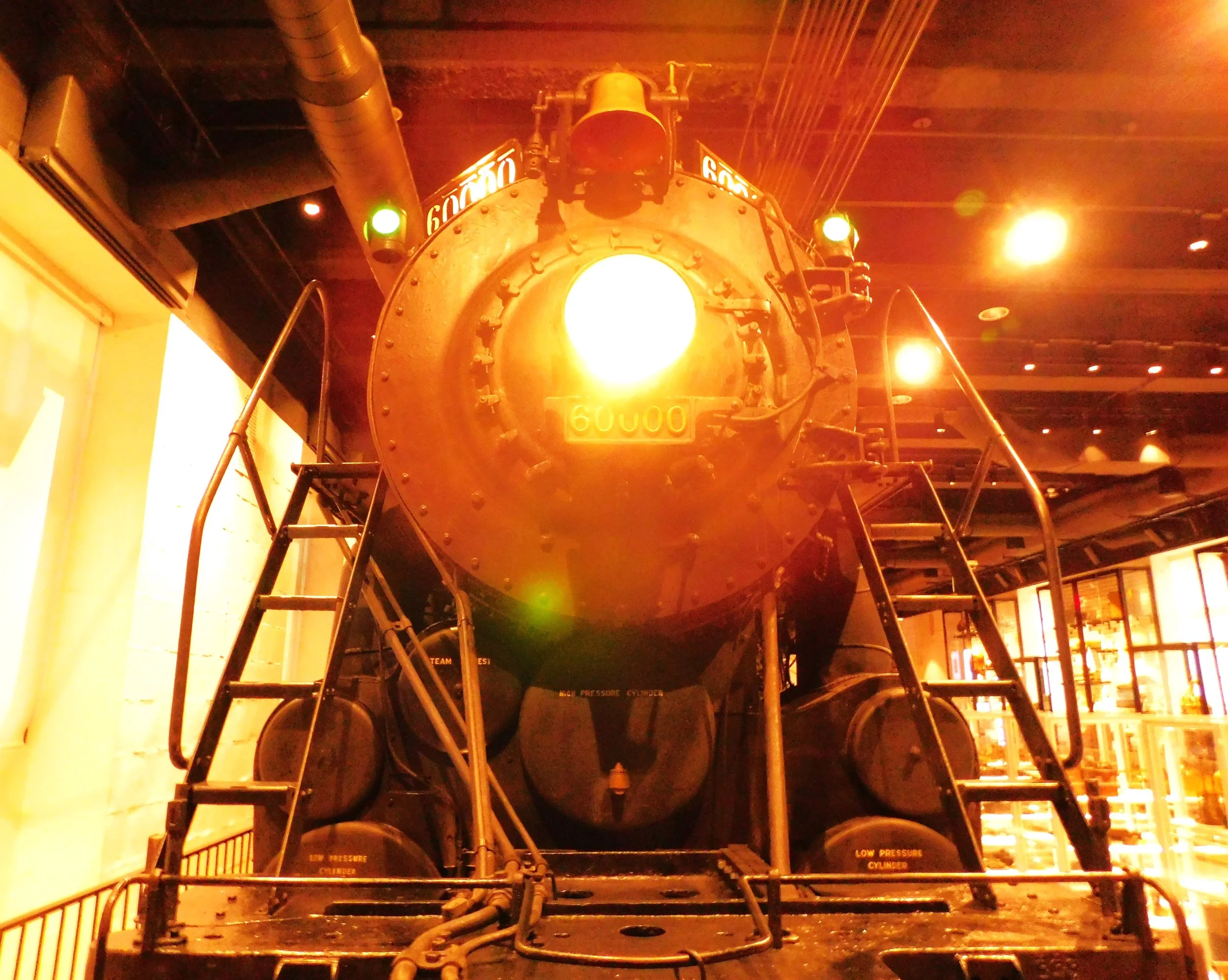

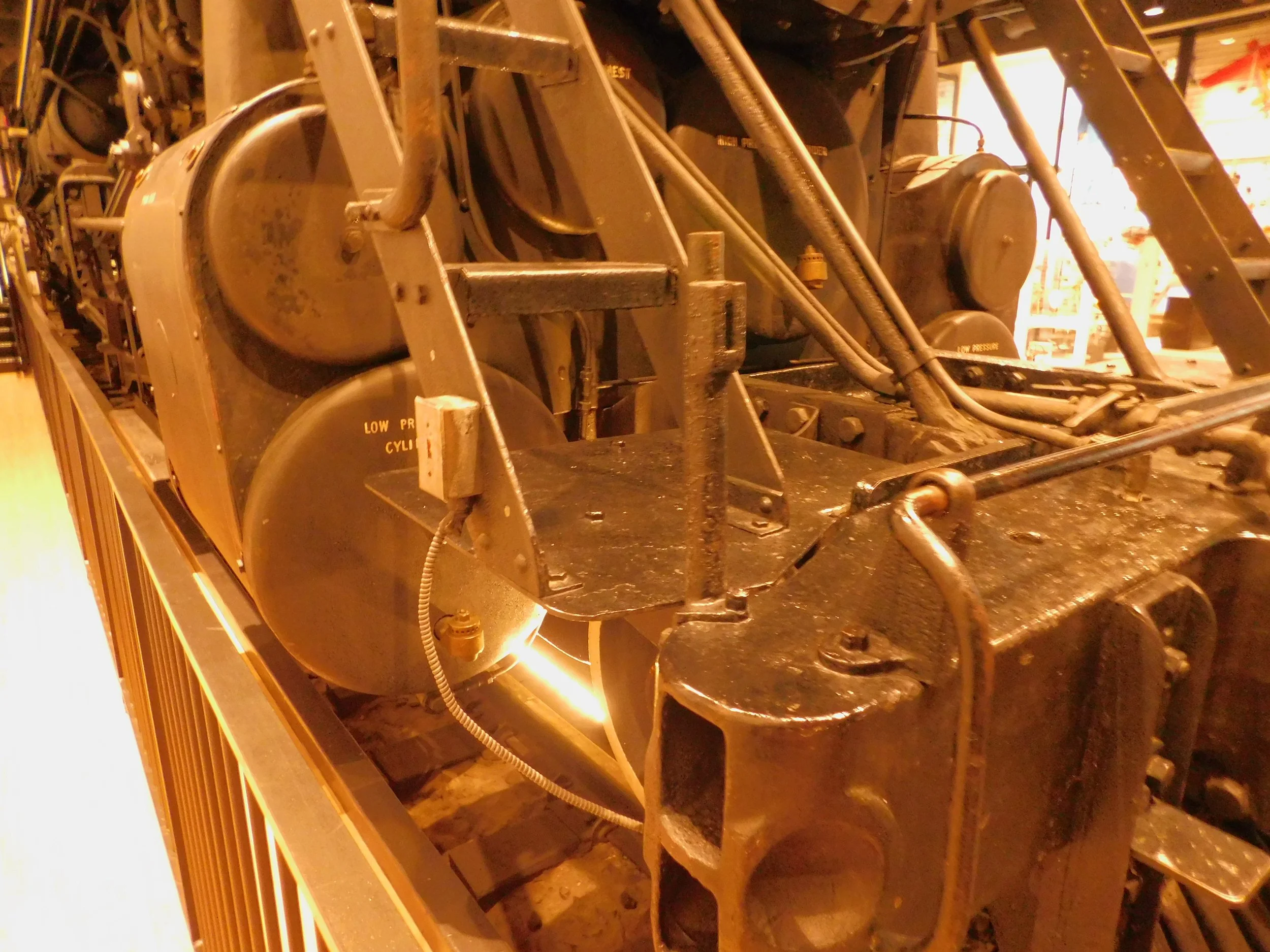

A third exhibit, which is always on my must-see list at the Franklin Institute, is this 700,900 pound locomotive- a Baldwin experimental steam engine. It bears the number 60000 to indicate it was the 60,000th locomotive built by Baldwin in the nearby Eddystone locomotive works.

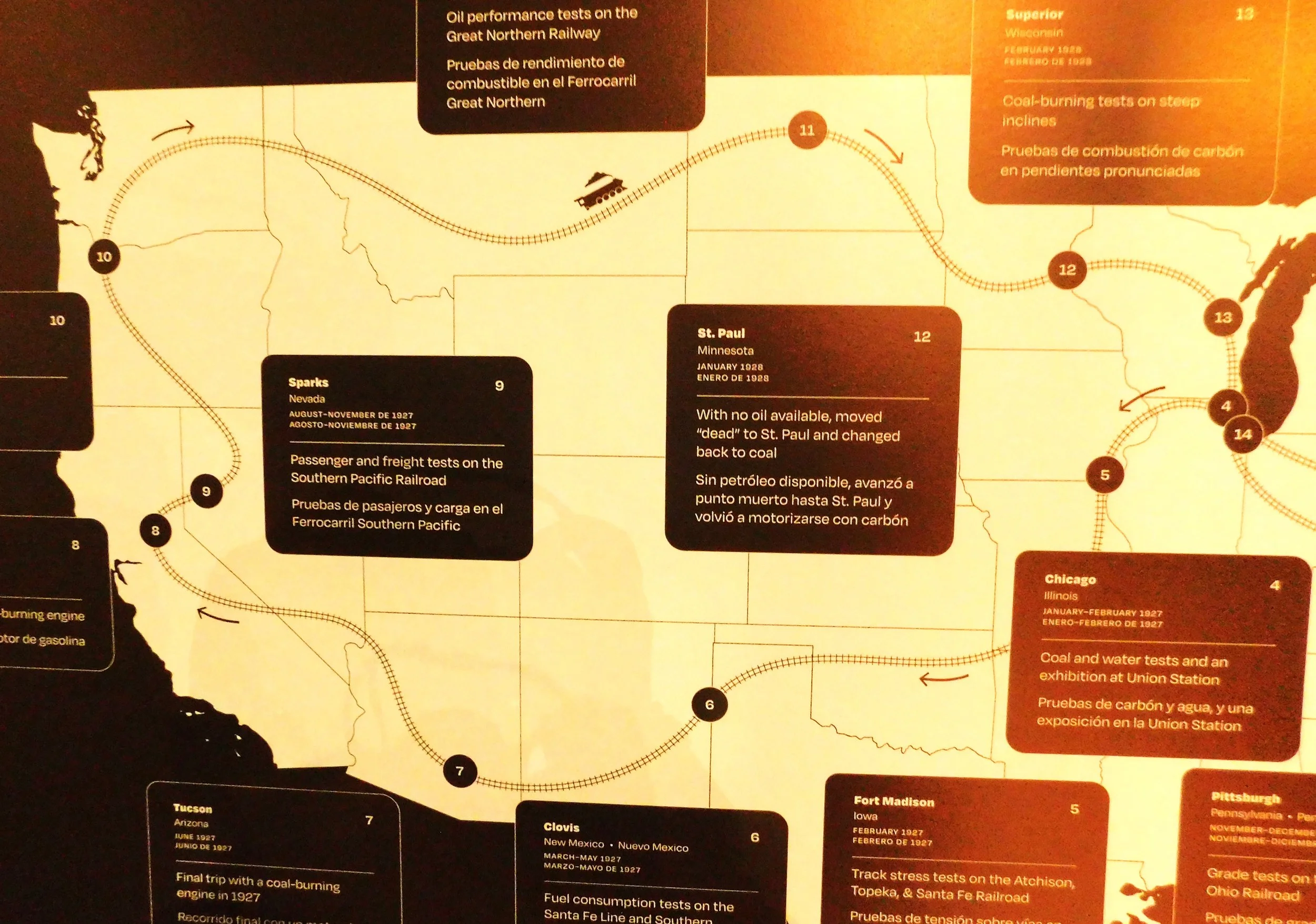

Built in 1926, the 4-10-2 engine was a test-bed for many innovations. During its years of testing, the locomotive was sent to all the major railroads in the country for evaluation and, hopefully, sales.

Map of the travels of Baldwin locomotive 60000

While testing in California with the Southern Pacific Railroad, it was converted to burn oil rather than coal, which was the practice of the SP. Unfortunately, no sales developed and the loco was returned to Baldwin and returned to being coal fired. For several years it was used as a stationary power source in their factory. In 1933, it was donated to the Franklin Institute which was in the process of building a new building (the one that stands today). Tracks were laid down through city streets and, in 1934, the locomotive was driven into place through a wall that had been removed. It remains in that spot today.

It is an imposing exhibit that visitors can climb in and around and even go underneath to look up at the mechanics of a steam engine.

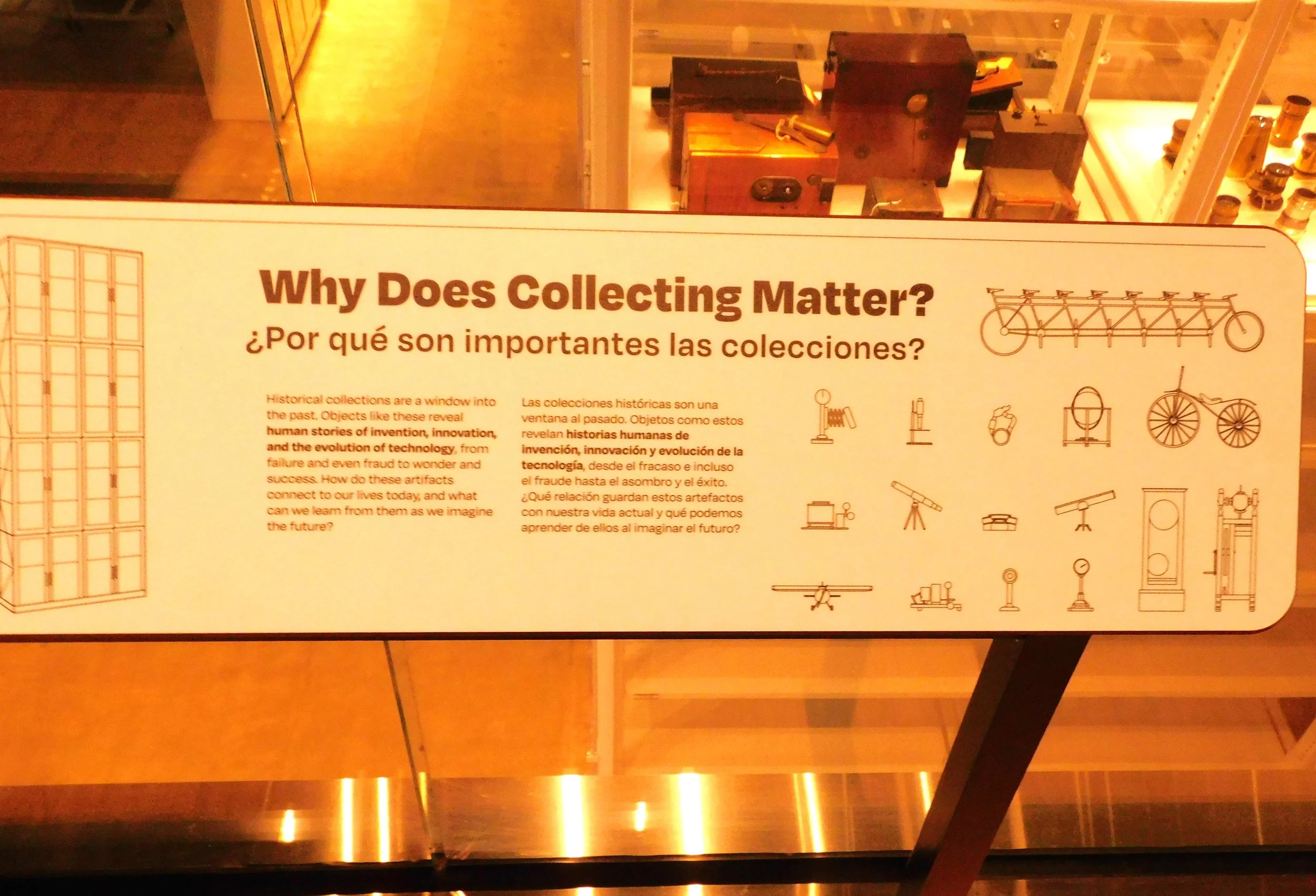

Although the loco is in the same spot that it has been in since 1934, the hall has recently been remodeled and named the Hamilton Collections Gallery. The interesting hall is lined with cabinets that are filled with significant artifacts of a wide variety of subjects.

“Why the emphasis on collections?” the plaque that introduces the hall asks. “Historical collections are a window into the past. Objects like these reveal human stories of invention, innovation, and the evolution of technology, from failure and even fraud to wonder and success. How do these artifacts connect to our lives today, and what can we learn from them as we imagine the future?”

A museum as old and as famous as the Franklin Institute has collected a huge number of artifacts over the years- only a small amount of which can be on display at any given time.

The format of the Collections Gallery allows for many items to be on display and the staff has done an excellent job of curating the cabinets which are well designed and well described. It is a room where you could easily spend all day and still not see everything. There are many aviation artifacts in the cabinets.

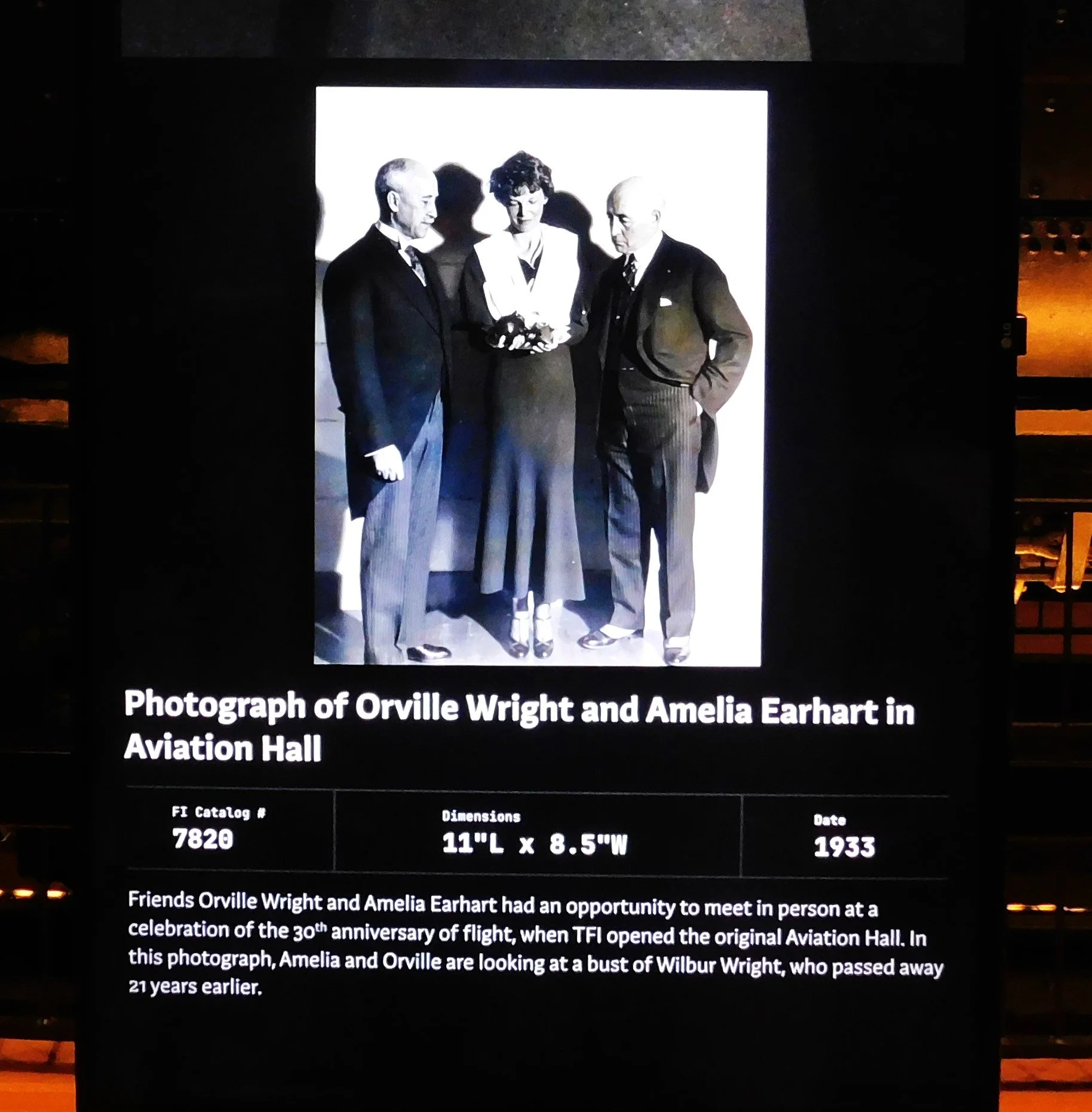

The items in the cabinets are all originals and range from every-day items to one-of-a-kind objects of historical significance. This photograph is of Amelia Earhart and Orville Wright at the Museum just after the new building opened, looking at a bust of Wilbur Wright.

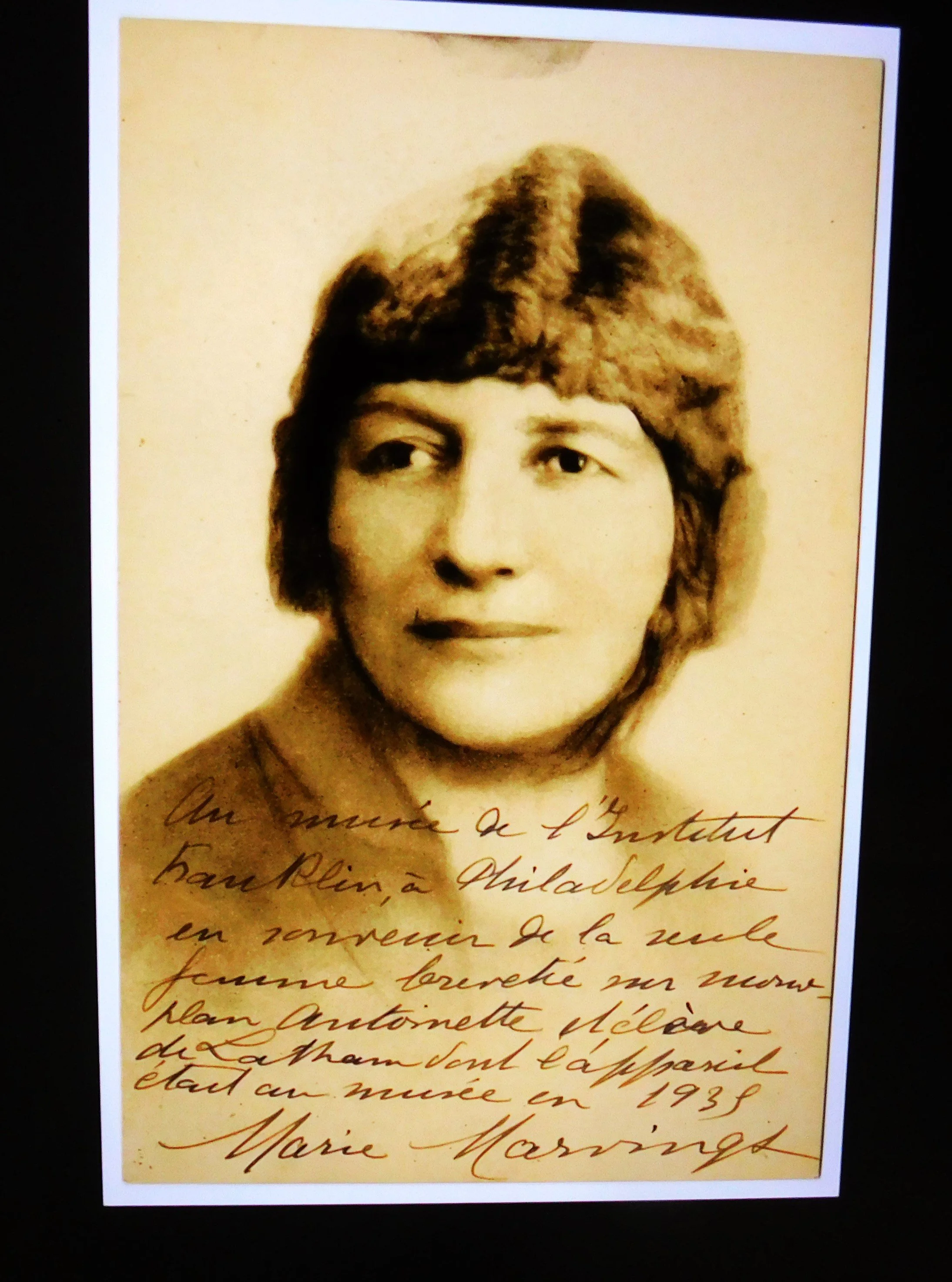

Marie Marvingt was a French athlete and aviator. In the years before WWI, she was famous for numerous athletic accomplishments in many fields such as swimming, mountain climbing, and cycling. In 1908 she was refused entry into the Tour de France because it was open to men only. She decided to ride anyway, cycling just behind the men. She completed the grueling three-week ride while only 36 of the 114 male starters finished.

Marvingt was also involved in aviation and, in 1909, was the first woman to cross the North Sea in a balloon. She was also the first woman to cross the English Channel in a balloon, in 1914. In 1910 she took flying lessons and received her pilot’s license in the difficult to fly Blériot Antoinette. During WWI, she flew several unofficial bombing missions, making her the first female to fly in combat.

Marie also worked as a journalist and qualified as a surgical nurse. As early as 1910, she advocated for aircraft to be used as air ambulances and her later life was devoted to promoting the idea of the air ambulance. She was co-founder of the French organization Les Amies De L'Aviation Sanitaire (Friends of Medical Aviation) and was also one of the organizers behind the success of the First International Congress on Medical Aviation in 1929. During WWII she organized the training of flying nurses.

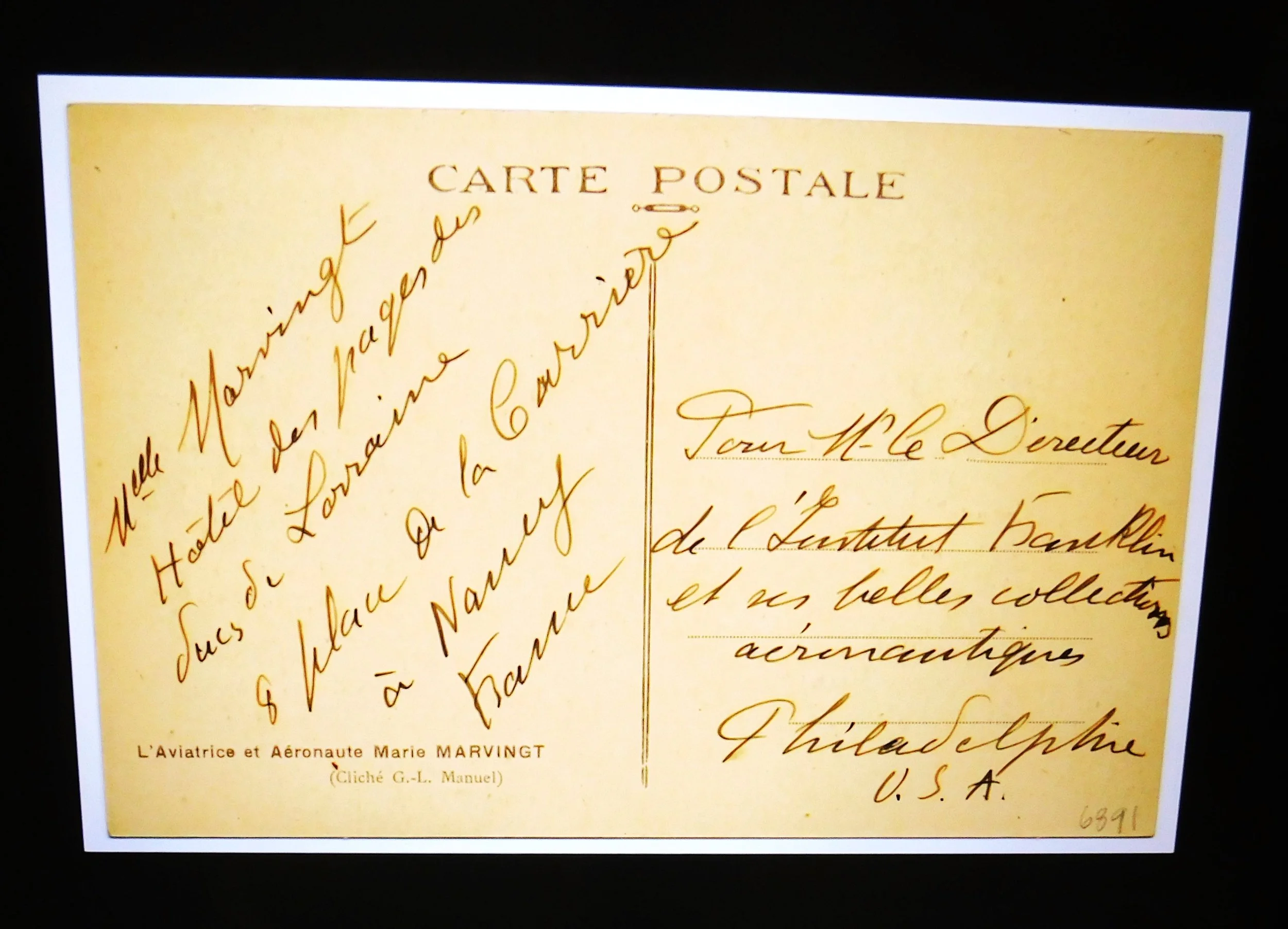

This postcard was received by the Franklin Institute in 1935, prior to Marvingt visiting the museum to give a talk. This simple artifact is displayed to illustrate and keep alive the story of Marie Marvingt, a true pioneer in aviation, who is little remembered in history, but deserves to be.

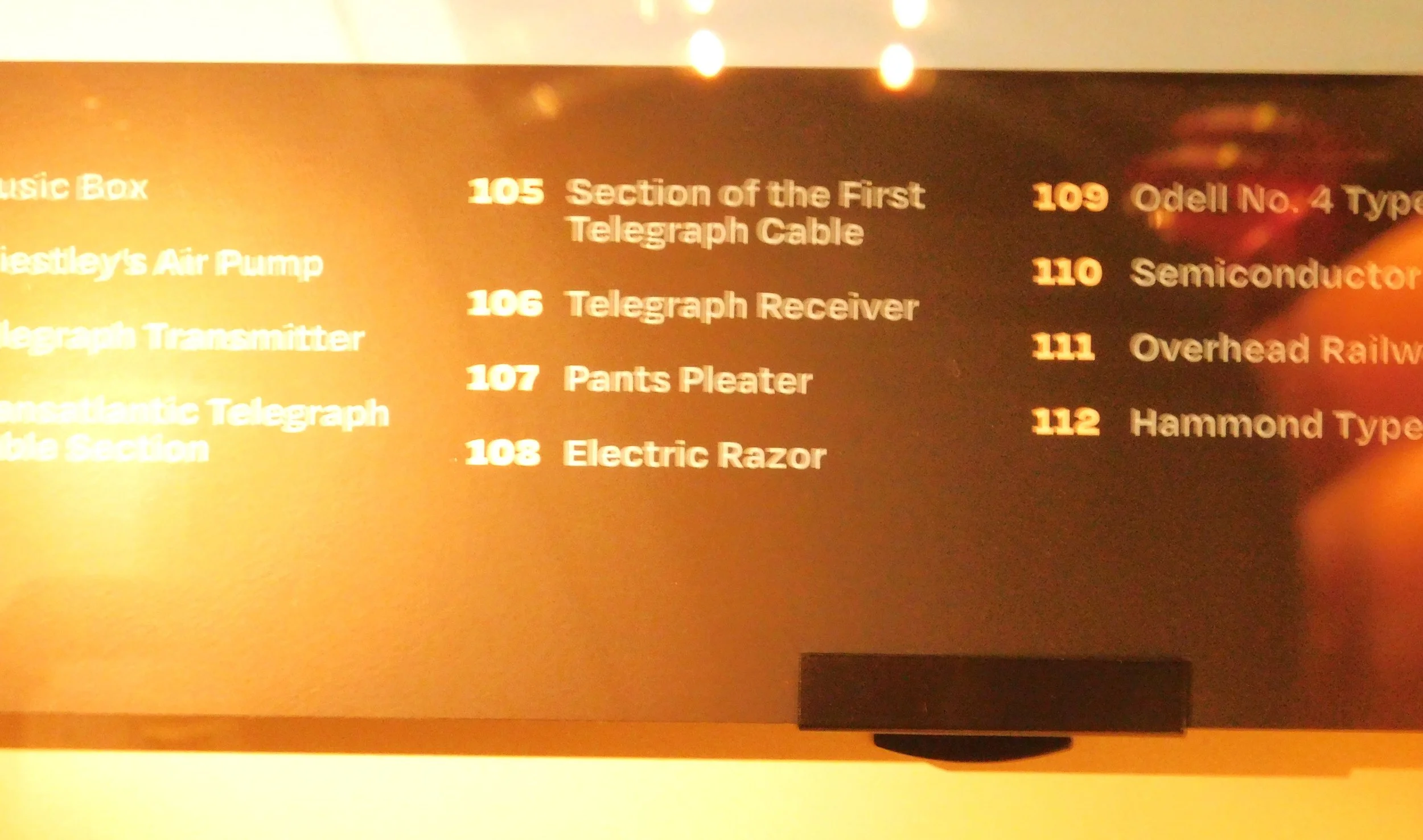

These are just two of the many cabinet directories, illustrating the great variety of artifacts on exhibit.

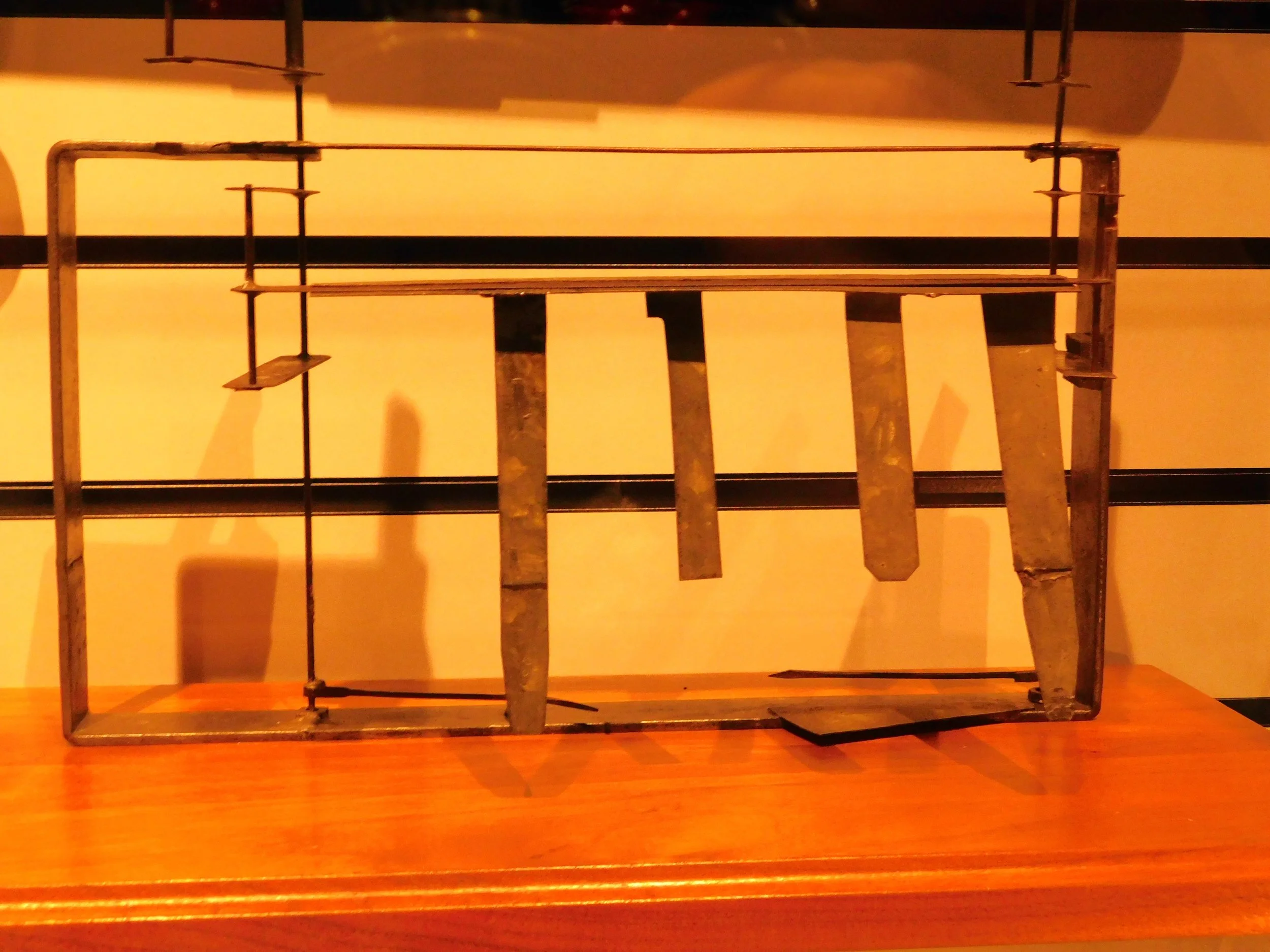

Many years ago, the museum was donated a large collection of Wright brothers’ artifacts and, until recently, only a few of them were on display. This new Collections Hall has allowed a greater number of these significant objects to be viewed and appreciated.

After their glider experiments in Kitty Hawk in 1900 and 1901, the Wright brothers were feeling a sense of failure. They had not made any progress in glider flying in 1901 and on the way home to Dayton, Wilbur famously remarked to Orville that “Not within a thousand years will man ever fly”. Not being willing to give up, though, they started evaluating their methods. They had been using data from the very successful glider builder and flyer, Otto Lilienthal. They decided to abandon his data and start from scratch. To this end, they built a wind tunnel to test various airfoil shapes. The original wooden wind tunnel no longer exists, but the Institute has an exact replica that was built in 1930. Above is the balance that was in the tunnel to hold the airfoils they were testing. The miniature airfoils are some of the actual ones that the Wright brothers made out of any scrap metal they had on hand. What they found was that Lilienthal’s data had been correct, but only for the one airfoil shape that he used. The wind tunnel tests showed a great variation in lift, drag, and balance created by different shapes. From these tests, the Wrights developed their own tables of data and these tests led to successful glider flights in 1902 and, of course, their first powered flight in 1903.

Even on days that my friends and I went to a different museum, I got to see this plane sitting in front of the Franklin Institute. This Budd BB-1 Pioneer has been on display in front of the museum since 1935.

Founded in 1912, the Budd company of Philadelphia, was formed to build steel automobile bodies. The company developed the use of stainless steel when company founder, Edward G. Budd, invented “shot-welding”- so that steel could be welded without losing its stainless properties. In the 1920s, the company moved to building railroad cars which they did until 2014, when they were bought by Bombardier.

In 1930, Budd decided to try their hand at stainless steel aircraft. They contracted with the Italian aircraft company Savoia-Marchetti for the use of their S.56 design. First flown in 1931 (from Budd’s own airstrip), the BB-1 logged about 1,000 hours before the project was abandoned. The Budd stainless steel version was 300 pounds heavier than the standard S-56, most likely the reason why it wasn’t put into production.

In 1935, the fabric was removed from the wings and it was put on display in front of the new museum building, where it has been ever since.

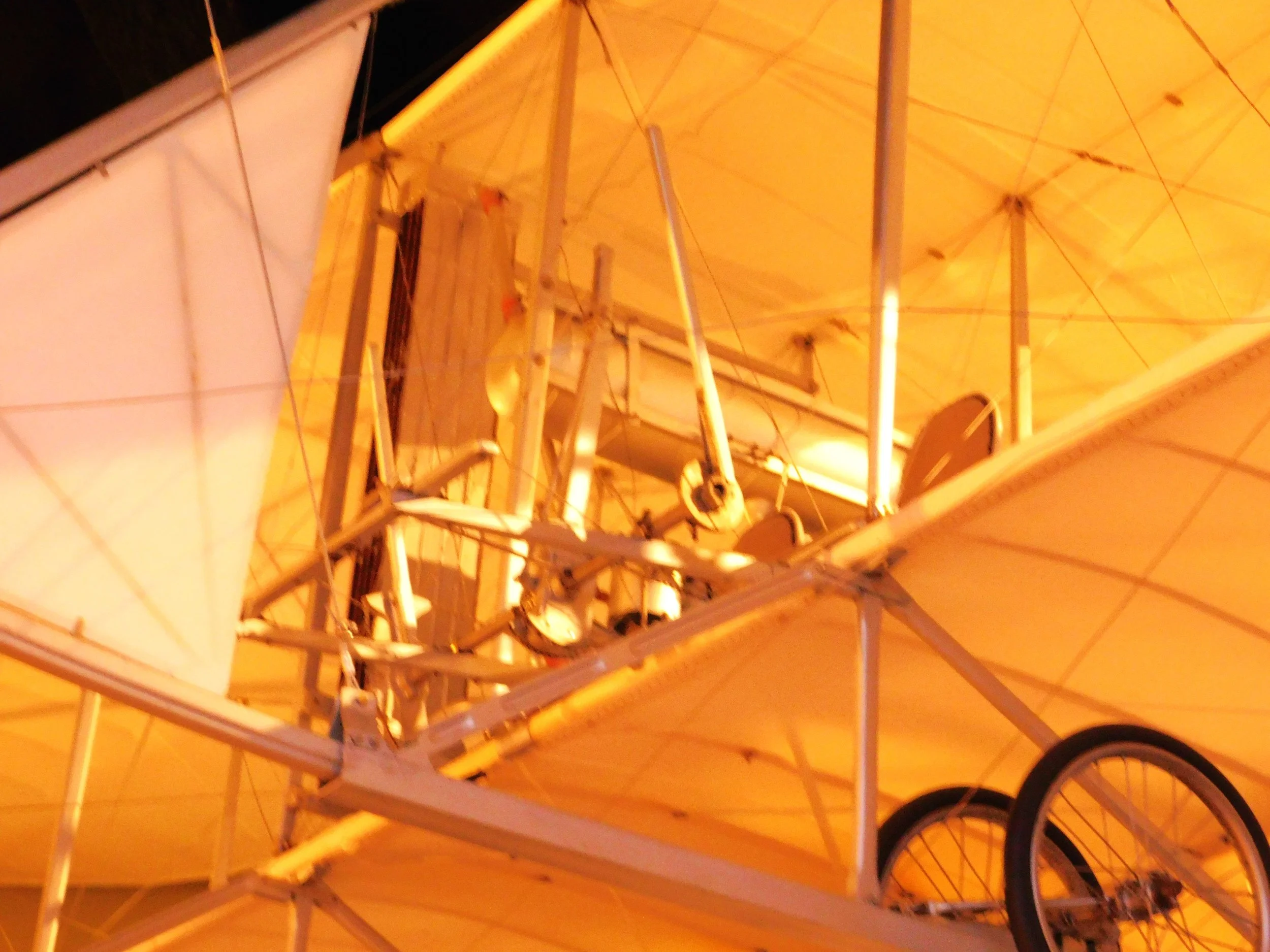

To finish up, let’s return to the Wright Flyer.

This Flyer is called a B model but it is not clear that the Wright brothers gave it that designation, they built many versions with just minor changes. Some of the designations were later added by historians, for clarity.

This Flyer was built around the same time as the first Wright Military Flyer- built for their military contract. All the early models looked similar, and, in fact, they are similar looking to the original 1903 plane. The main visual difference is that the elevator was moved to the rear, which has some aerodynamic advantages. The Wrights originally put the elevator in front, partially for safety reasons. The elevator would provide some amount of protection in a crash, of which there were many.

A second difference to earlier models was the control levers. The controls on the original two-seaters were opposite for each seat. The left seat pilot used his left hand to operate a lever for the elevator and his right hand operated a lever for the rudder and for wing warping. The right seat pilot used that same lever with his left hand and a third lever on his right controlled the elevator. This arrangement resulted in “left seat pilots” and “right seat pilots”; the control feel for these early pilots was quite different, depending on which seat they were in. Later models added a fourth lever so that each pilot had identical controls. Wilbur preferred the four lever system for planes that he flew, while Orville stuck with the three lever version, like this one.

The Franklin Institute, like the Smithsonian, has so much to see, it is impossible to appreciate everything in one visit. Members have free entry and so a membership not only supports the museum, but allows multiple visits and gives you an interesting monthly newsletter. Either way, this is a great historic museum to visit.

Many thanks to Susannah Carroll of the Franklin Institute for her assistance on this blog.

-------------------------------------------------------------

When I visited the Franklin Institute last month I had no idea that the day before this blog went out, the front of the museum would be jammed with 10s of thousands of people celebrating a Super Bowl win. Congrats Eagles!

To learn about museum hours and costs as well as books to read and other interesting odds and ends, keep reading! At the end you will find a photo gallery of the entire museum.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

The Franklin Institute is open daily from 9:30 am - 5:00 pm.

Closed New Year's Day, Thanksgiving Day, December 24, and December 25.

Adults (18+) $29

Youth (13-17) $25

Child (3-12) $23

Members Free

FLYING IN

Located in downtown Philadelphia, The Franklin Institute is not on an airport. Airports to consider- with approximate driving time: Philadelphia International (PHL) 17 mins, North Philadelphia airport (PNE) 22 minutes, Wings Field (LOM) 36 minutes, Brandywine Airport (OQN) 47 minutes.

MUSEUM WEBSITE

SUGGESTED READING

“I guess there are never enough books.” John Steinbeck.

The William E. Boeing Story: A Gift of Flight, by David Williams is an interesting and different look at the life of Bill Boeing. Goodreads describes the book this way “The William E. Boeing A Gift of Flight is the first ever full-length biography of William E. Boeing, the father of commercial aviation. Boeing's story is an exciting one, complete with bootleggers, kidnappers and disastrous run-ins with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black. Boeing's story covers every aspect of early aviation, starting with his first ride in a balloon in 1896 to the christening of the revolutionary jet-powered Dash-80/707 in 1955. Along the way Boeing developed some of the world's most iconic airplanes including the P-26 Peashooter, the Boeing 247, the B-17 Flying Fortress and the mighty B-29 Superfortress. The Boeing family have given author David D. Williams unprecedented access to the Boeing family archives which contain thousands of never- before-seen photos, diaries, and personal letters. This treasure trove of primary sources has allowed Williams to create an extraordinarily vivid and accurate portrait of this influential yet private man.”

Many thanks to reader and friend Steve Taylor for recommending this excellent book.

WRIGHT BROTHERS STORIES

After their first flight in 1903, The Wrights continued their experiments at Huffman Prairie, near Dayton. Because they would not have the consistent winds that they had on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, they devised a basic catapult launch system, which they called a “starting apparatus”,

The device used three pulleys to gain mechanical advantage. The aircraft launched from a rail that had been laid down into the wind (as they had in Kitty Hawk). The catapult rope went from the tower, under the aircraft, through a pully around 65 feet along the track and back to a hook on the front of the plane. The pilot would start the engine and let it warm up and, when ready, he would pull a trigger which would release the weights at the top of the catapult tower. The plane would accelerate. When it reached the pully, the rope would drop off, the plane would continue accelerating under its own power, and soon go airborne.

Replica of Huffman Prairie catapult Photo: Carol Highsmith

UP NEXT

Hagerstown Aviation Museum

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

As you travel the moving sidewalk towards the gates in Philadelphia’s international terminal, off to your right, above the departure hall, is an amazing sculpture titled “Impulse” by artist Ralph Helmick.

Photo Courtesy of Will Howcroft Photography

The sculpture is a series of six mobiles that morph from birds sitting on wires into a DC-3. I’ll let the artist’s web site describe it properly.

“Impulse is a three-dimensional “flip book” wherein a series of six sculptures morphs in an evolving sequence of flight-related forms.

Photo Courtesy of Will Howcroft Photography

The sequence is oriented east to west, the easternmost section illustrating birds on implied wires, surrounded by companions beginning to fly. Moving west the birds begin to flock, eventually arranging themselves into an epic goose, which in turn transforms into a classic DC-3 aircraft.

Photo Courtesy of Will Howcroft Photography

A moving sidewalk on the second floor of the terminal furnishes an optimal interface for interested viewers, who may contemplate not just the physical phenomenon of the artwork, but the essential rapture that links both natural and manmade flight.

Photo Courtesy of Will Howcroft Photography

For this commission the studio created over fifty wax sculptures depicting various avian species. These nearly life-size forms were scanned, scaled and converted into rapid prototypes from which molds were made for multiple castings.

The final composition is comprised of over 6750 pewter components.”

While flying international trips out of Philly, I tried several times to take pictures of this amazing sculpture, but I could never do it justice. These photos, from the artist’s website, do much better than I did, but I assure you it is much more dramatic in person

https://helmicksculpture.com/work/impulse

Many thanks to Ralph Helmick for his assistance on this segment!

PHOTO GALLERY

Click any photo to enlarge

Issue 51, Copyright©2025, Pilot House Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

Permission to post or share this blog is granted to all- please credit AviationHistoryMuseums.com

Except where noted, all photos are by the author