Fleet Air Arm Museum

Issue 46 A visit to the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton, England (Part 1) April 2024

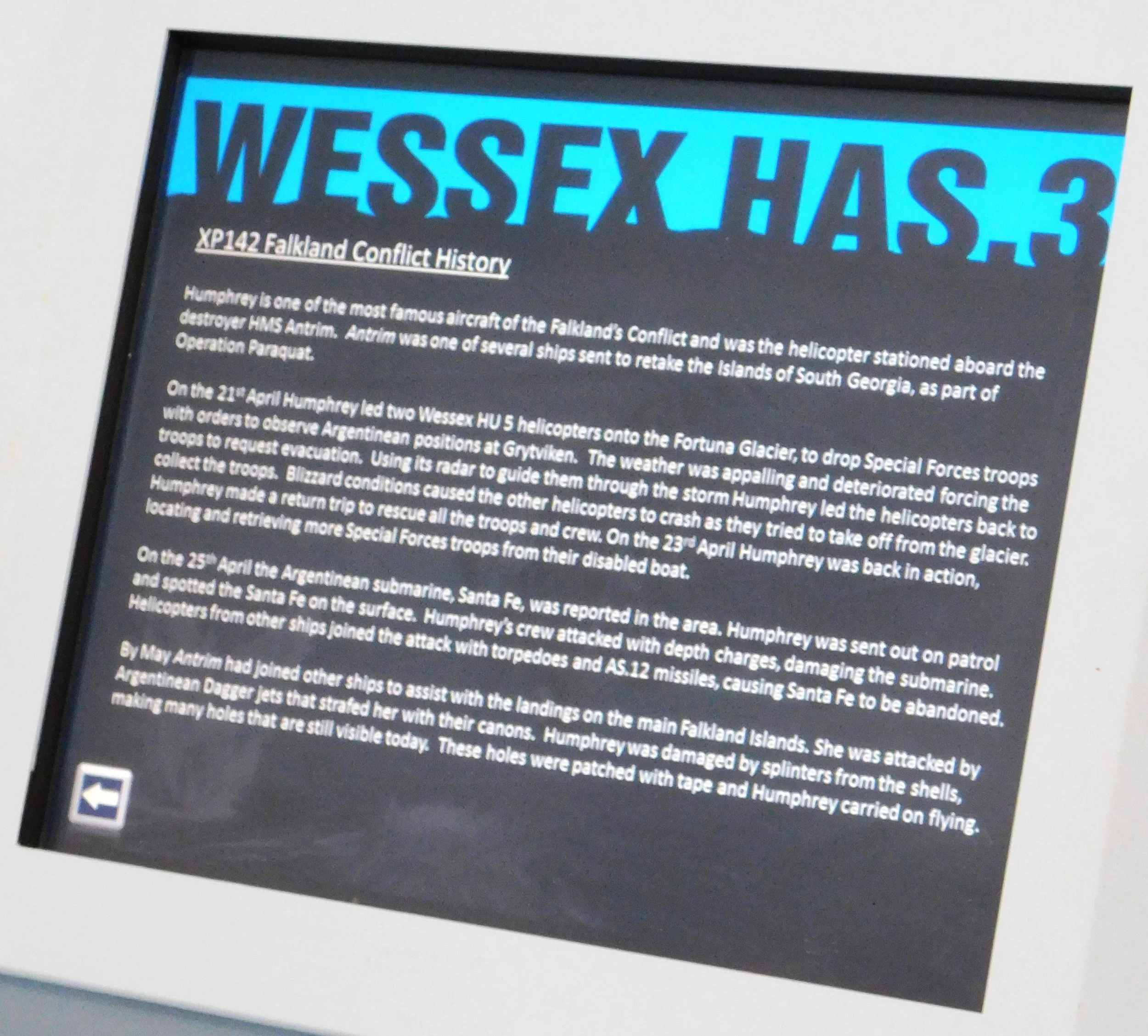

For 10 weeks in 1982, the United Kingdom and Argentina were at war over the Falkland Islands. The war began on 2 April when Argentina launched Operation Rosario and occupied the Falklands. Britain immediately responded by sending Naval and Air forces to Argentina. The long supply chain and challenging topography made the re-taking of the Islands a difficult task. The first British response on the Islands, on 21 April, was an attempt to establish a lookout post on the Fortuna Glacier, on the island of South Georgia. Royal Marine Commandos were landed on the glacier, and planned to establish a force of several hundred troops at this unexpected position. The attempt was foiled by harsh weather and, by the following day, the first group of troops were stranded in blizzard condition. Three Westland Wessex helicopters, operating from Royal Navy ships, which had dropped the troops, were dispatched to try to a difficult rescue. On their second attempt, in white out conditions, the rescuers made contact. After picking up the troops, one of the helicopters, a Wessex 5, crashed during takeoff. Its passengers and crew were not hurt and they scrambled out of the wreck and onto the two other helicopters. A second Wessex 5 clipped a ridge on departure and crash landed. Only the Wessex 3, which was operating off RMS Antrim, was able to leave with rescued soldiers. The two hull losses were the first losses of the Falklands War. The passengers and crew of the two downed helos had all survived but were still stranded on the glacier. The third Wessex, flown by Lt Cdr Ian Stanley, returned to the glacier later in the day. Still flying in 70 knot blizzard conditions, Stanley was able to locate the remaining men, and take them aboard. Although severely overloaded, the Wessex was able to reach the Antrim and all survived. Lt Cdr Stanley received the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his bravery. Four weeks later, on 14 June, Argentina surrendered.

The helicopter flown by Lt Cdr Stanley, which was affectionately named ‘Humphrey,’ continued to serve throughout the Falklands War and is now on display at the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton, UK.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

Located on Royal Naval Air Station Yeovilton in the West of England, the Fleet Air Arm Museum was established in 1964. Originally the museum contained about half a dozen aircraft in a small hangar. Today it has grown into a large museum with almost 100 aircraft, over half of which are on display at any one time. There are significant aircraft on display and numerous interesting features in this museum. There is so much to see that I will cover the Fleet Air Arm Museum in two blogs.

The museum is divided into four main halls, and, as you enter, Hall number 1 is to the left. The facility has many staff members available and a greeter was at the entry to give visitors an overview of their visit.

HALL ONE

Titled “A Celebration of Naval Flying”, this hall contains a variety of aircraft and displays illustrating the development of Naval Aviation.

This is a replica of one of the earliest Royal Navy Aircraft, a Short S.27.

Founded in London in 1908, Short Brothers Aircraft was developed from a hot air balloon business the brothers founded in 1897. In 1909, the Short Brothers built a factory on Aero Club land on the Isle of Sheppey. They received an order to build six Wright Model As under license and became the first company in the world to build a production aircraft.

The Short Brothers soon began designing and building their own planes, including the S.27. In 1912 Charles R Samson, piloting a Short S.27, made the first takeoff from a moving ship, the battleship HMS Hibernia. During WWI, Short Brothers manufactured several seaplanes including the Short Type 184, a two-seat reconnaissance, bombing, and torpedo plane. The folding-wing seaplane was first flown in 1915 and remained in service until after the armistice in 1918. A Short 184 was the first aircraft to sink a ship using a torpedo.

Photo Courtesy: Fleet Air Arm Museum

This Short 184, 8359, which is on display in Hall 1, was the only British aircraft to take part in the Battle of Jutland in 1916. It was a ship-based observation plane flown by Flt Lt Frederick Rutland (known forever after as Rutland of Jutland) and he was responsible for locating and reporting four German cruisers. After WWI, the plane was presented (in good condition) to the Imperial War Museum, where it was damaged during the London Blitz. On loan from the Imperial War Museum, it is displayed in the condition it was in after the WWII attack.

Following WWI, the Short Brothers continued designing and building military aircraft, including the WWII seaplane, the Sunderland. In 1936, Short Brothers manufacturing moved to Belfast, Northern Ireland, where it continues today (as part of Bombardier, since 1989).

Displayed with its wings folded, this Supermarine Walrus L2301 was built at Southampton in 1939 and was originally intended for the Fleet Air Arm. As WWII was nearing, it was delivered instead to the Irish Air Corps, where it was designated N.18. On its delivery flight it suffered an engine failure and was damaged during the sea ditching. It was towed to a former U.S. Navy station in Wexford Ireland where it was repaired. It was one of three Walruses that flew coastal patrols in Ireland during WWII. In 1942, this plane was stolen by four Irish nationals who attempted to fly it to France, with the intention of joining the Luftwaffe. The hijackers were intercepted by RAF Spitfires and forced back to Ireland. After the war, the plane was transferred to Aer Lingus, but it never flew for that airline, winding up instead in private hands for recreational flying. It was salvaged from a dump in 1963.

First flown in 1933, the Walrus was designed by Spitfire designer R.J Mitchell. Produced from 1936-1944, 740 of the type were built. Serving as patrol aircraft, many were based aboard ship. During WWII, almost 25% of Royal Navy ships had a catapult installed. The Walrus (and other types) could be launched at short notice and recovered ashore or craned back on board after landing alongside the ship. This is one of only four surviving Walruses.

It is not surprising that this museum of Royal Navy Aviation contains a number of helicopters. Although not the first helicopter in the Royal Navy, this Westland Dragonfly represents early development of this type of craft. The Dragonfly was the first British built helicopter to operate from a Royal Navy ship. It made up 705 Naval Air Squadron, which may have been the first all-helo squadron outside of the U.S. The Westwind probably looks familiar as it is a license-built version of the Sikorsky S-51, which was used extensively throughout all arms of the U.S. military.

This Dragonfly, VX 595, was built in 1949 and was the first production model of the type. It was used for training at the Empire Test Pilot School at Boscombe Down.

Next in line is the Wessex HAS 3, XP-142, - ‘Humphrey’ from the opening story. Typical throughout the museum are the placards that accompany the aircraft on display. They thoroughly describe the type as well as the history of the specific aircraft. Whether you are a casual visitor or a student of aviation history, this kind of detailed information adds interest to your visit.

This Westland Sea King, XV 663, was primarily designed as an anti-submarine helicopter and is fitted with ASW equipment. It is one of those types of exhibits I love to find in museums- totally open for public access.

Another veteran of the Falklands War, this was one of four helicopters that participated in rescuing troops from two burning landing craft.

Although this Sea King served in the Royal Navy, the type also served in the RAF and one side is painted in Navy colors while the other is in RAF colors

Like the Dragonfly, the Sea King is a license-built version of a Sikorsky product, the S-61. The U.S. Navy version was also called the Sea King (Navy designation- SH-3) and it was used extensively from 1959 to 2006.

HALL 2

After passing the Sea King, you enter Hall 2 through a small door. This second area is named- “Through the Wars, WWII and Korea”. Just a note here- as you travel through the museum, entryways such as this can be small and partially hidden. Be sure that you investigate all areas- it is possible to miss some of the great displays.

As you can see from this photo, there are various places in each hall where you can view displays from above- another great aspect of this museum.

The first plane you come to in Hall 2 is this Fairy Fulmar. Illustrating the vital need for military aircraft at the beginning of WWII, the Fulmar made its first flight in January of 1940 and was put into regular service in June of 1940. The Fulmar was not a spectacular performer, but it was sturdy and reliable and served well as a carrier-based reconnaissance and light bomber aircraft. It was also used as a night intruder aircraft. Powered by a Rolls Royce Merlin, 600 of the type were built.

This Fulmar, N1854, was the prototype and first production aircraft and is believed to be the only surviving example.

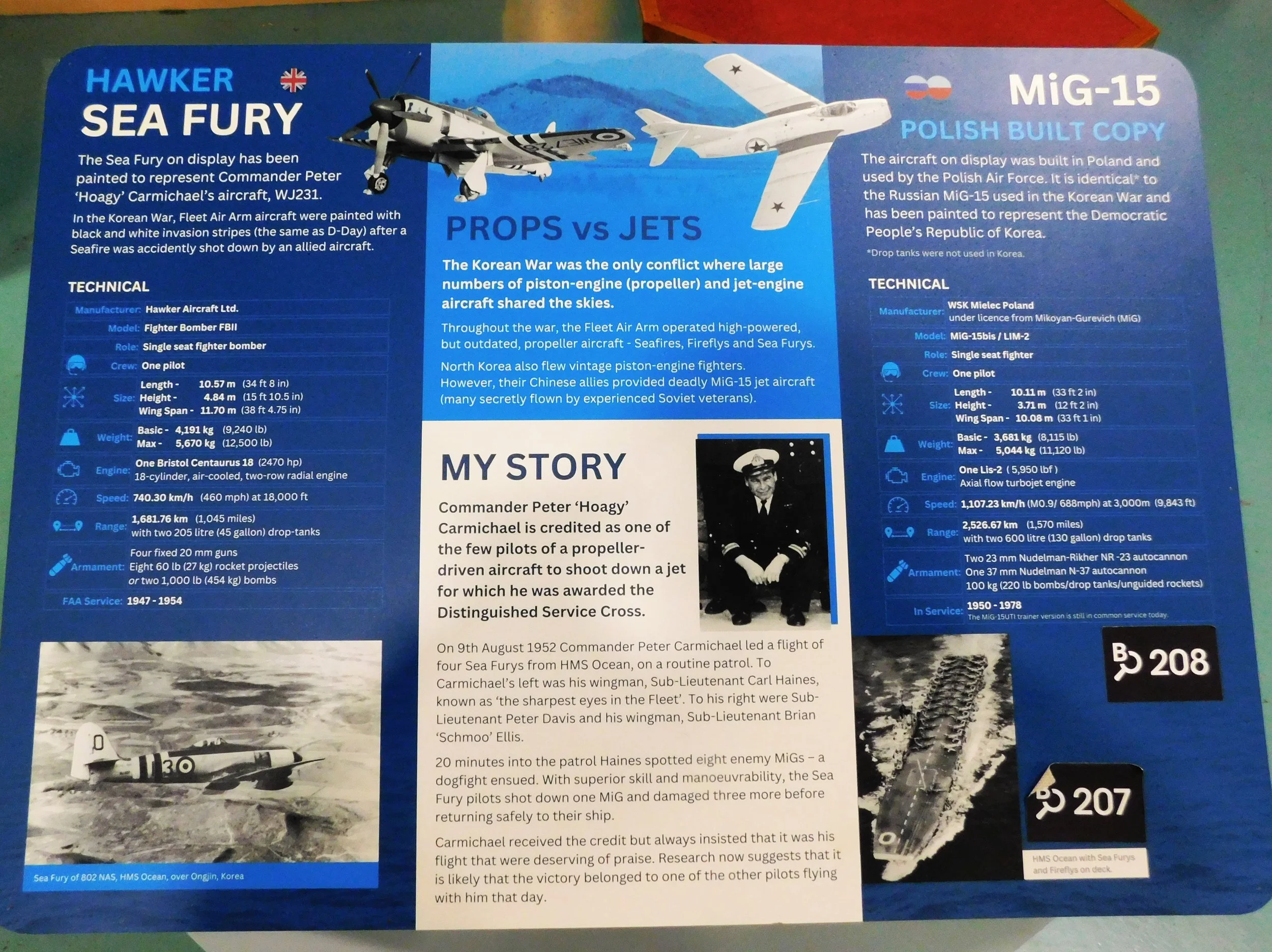

As with the helicopters in the previous hall, there are some familiar looking aircraft in Hall 2.

This Grumman G-36A Martlet I is a version of the F-4F Wildcat which was ordered by the French Aeronavale in 1940. Before the aircraft were delivered, France fell to the Germans and Britain took over the contract. Of the 91 built, only 81 were delivered to the Royal Navy, as 10 were lost to U-boats during the Atlantic crossing. The Martlet differed from early F-4Fs by having different armament, non-folding wings, and a more powerful Wright R-1820 engine rather than the original Pratt & Whitney R-1830. Later F-4Fs adopted this engine including all those built by General Motor’s Eastern Aircraft Division, which were designated the FM-2. Like the F-4F, the Martlets served throughout the war and, by 1944, the British had adopted the Wildcat name.

This Martlet I, AL-246, is the only surviving Martlet I. It served most of the war based in Scotland and later as a training aircraft. It has been part of the museum since 1964. There is little documentation about this interesting group of 81 aircraft and the museum has made it a continuing research project. There are details about that research on several of the accompanying placards, including facts about the colors of the paint. Some of the paint is original and some has been restored- which has been painstakingly researched. It is believed that the colors on display are how it was originally painted, but research continues.

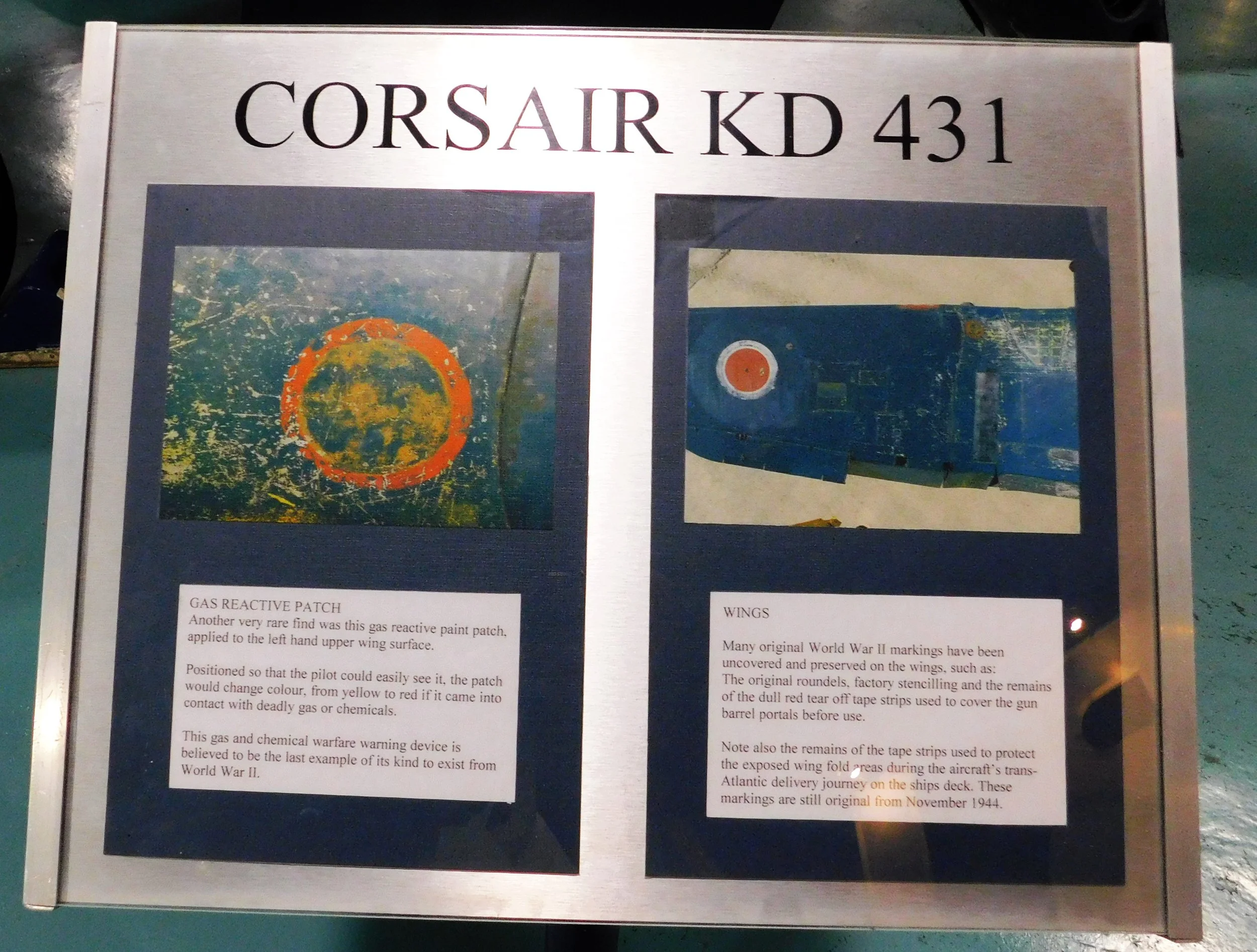

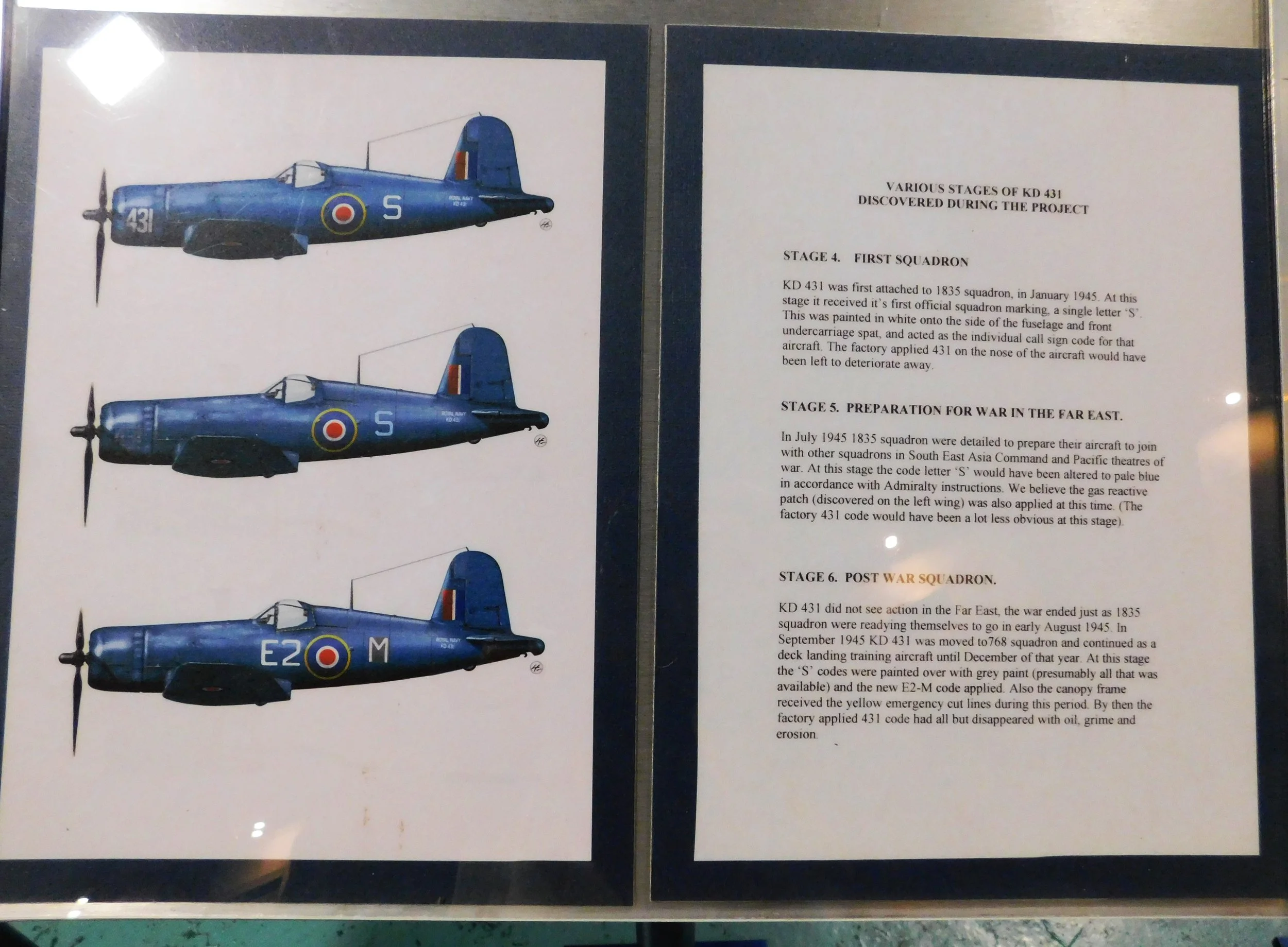

Another example of an aircraft on display that tells visitors much more than just basic information is this RAF Corsair KD 431. This plane has been the subject of many years of forensic restoration resulting in what may be the most original Vought F4U Corsair in existence. Like the Martlet above, very careful attention was paid to the paint layers on the aircraft and what they can tell about the history of the plane. Some of the findings are described on the placards. There were six levels of paint found, representing the different squadrons it was attached to.

There was also a unique and unusual gas reactive patch uncovered. The patch (left, above), which would change color if it came into contact with deadly gas, was visible from the cockpit.

Markings on the tail indicate that that part may have been manufactured by Brewster Aircraft on Long Island rather than by Goodyear in Arizona where this plane was built. By the time this plane was built, in 1944, the Brewster factory had ceased production of Corsairs. It is theorized that some parts that were already built (such as this tail) were shipped to to Arizona after production stopped on Long Island. The reason this is suspected is that the bottom layer of paint found on the tail is in colorings not used at the Arizona factory.

There were other interesting artifacts discovered on the plane including a small piece of yellow tape that would have been in place for protection during the Atlantic crossing when delivering the aircraft.

Having flown a 1950s era aircraft (Grumman C-1A) on and off aircraft carriers, I have a great respect for the skills required to operate off carriers of that time. The C-1, however, was a straight wing, piston powered plane- much easier to land on a carrier than a jet, especially early jet fighters. The de Havilland Sea Vampire was the first Royal Navy jet aircraft to land on a carrier (in fact, it was the first pure jet to land on any carrier). Lt Commander Eric “Winkle” Brown made the landing in December 1945 on the HMS Ocean, in less than ideal weather conditions. The plane he was flying, Sea Vampire LZ551/G is the aircraft on display.

This aircraft was one of the three original prototypes of the Vampire. The main changes to make it a Sea Vampire were the addition of a hook and larger speed brakes (for higher power, lower speed approaches). The twin boom design of the Vampire puts the hook (center left, above) in a more forward location than other carrier aircraft, which I imagine added one more degree of difficulty to a carrier landing in this jet.

The de Havilland Vampire was quite successful, with over 3,000 being built. De Havilland had built the Mosquito during WWII and, based on that experience, they had used similar plywood construction to build the Vampire. The forward section of the Vampire fuselage is mainly plywood, while the aft section is mainly aluminum.

Near the Sea Vampire is the cockpit portion of another Vampire, XA-127. This is one more of the great features of this museum. Visitors can climb up and sit in the actual cockpit.

XA-127 was a T-22 model- a two-seat trainer. The accompanying placard gives all the pertinent information about the Vampire, as well as labeling all the controls and gauges.

Many aircraft on display in museums throughout the world, especially WWII era planes, have been recovered from underwater. Museums often mention this on the display, but very few actually display items underwater.

The American Airpower Museum on Long Island (issue 40) displays this landing gear that was pulled up in a fishing net off Shinnecock Inlet in 2013. It is assumed to be from a B-24 that went missing on a training flight in 1944. It is displayed in the condition in which it was found - resting on the ocean floor- actually in water (and it’s a live fish).

The Fleet Air Arm Museum takes the idea to an entirely different level, by putting the visitor down with the artifacts, on the ocean floor.

As you enter this room, you are in the middle of an underwater diorama, with the remains of a crashed aircraft in front of you. The plane is Blackburn B-24 Skua, L2940, which went down in a lake in Norway in 1940. Three Skuas from 800 squadron took off from HMS Ark Royal for a patrol flight. They spotted a Heinkel 111 and all three attacked, forcing the Heinkel down on a snowy mountain. One of the Skuas had engine problems and landed on a frozen lake in the same area. The crews of the two planes wound up finding the same hut on the snowy mountain and they worked together to survive. Eventually, they were found by a Norwegian patrol and the Germans were taken prisoner. This event was the basis of the film “Into the White”.

In 1974, the Skua was recovered by the Naval Air Command Sub Aqua Club. The recovery efforts are illustrated throughout the diorama. It is really a unique display.

Let’s finish up with a little more about “Humphrey” from the opening story.

The Westland Wessex was a development of the Sikorsky H-34. The H-34 served for years in the U.S. Navy, powered by the Wright Cyclone R-1820 radial engine. In 1958, an H-34 was shipped to the Westland factory (in nearby Yeovil) where it was modified to be turboshaft powered. The first versions had one engine while later models, like Humphrey, were powered by two Rolls-Royce Gnome turboshafts. From 1958 to 1970, Westland built 382 of the various Wessex models.

-------------------------------------------------------

This is a great museum and well worth the visit. We will continue our tour in Halls 3 & 4 next month- including an amazing re-creation of parts of an aircraft carrier as well as a Concorde prototype.

Many thanks to Conor O’Hanlon, Content and Communication Executive for the museum, who helped me with my research, as well as all the museum staff who were happy to answer questions during my visit.

--------------------------------------------------------

To learn about museum hours and costs as well as books to read and other interesting odds and ends, keep reading! At the end you will find a photo gallery of the museum.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

The Fleet Air Arm Museum is in Yeovilton in the West of England. It is convenient on any trip to the West or Southwest of England. It is 40 miles from Stonehenge, 30 miles from the historic town of Bath, and 50 miles from Bournemouth, on the south coast. For music fans, it is just 18 miles from Glastonbury.

Open 10am to 4.30pm, Wednesday to Sunday

Adult £22

Child (3-15) £16

Senior £21

There is a discount if tickets are purchased on line and there are also family discounts available.

SUGGESTED READING

“I guess there are never enough books.” John Steinbeck.

Three towering figures in early American Aviation; Eddie Rickenbacker, Jimmy Doolittle, and Charles Lindbergh, have had much written about them over the years. But as Steinbeck says ”there are never enough books”. In the case of these three figures, Winston Groom’s the Aviators, weaves the three overlapping stories together in a very enlightening and entertaining way. Even if you are familiar with the three stories, you will find this an excellent read.

My son Eric gave me this book as a gift- thanks Eric!

WRIGHT BROTHERS STORIES

In the section above, about the Short Brothers, I mentioned that they produced a batch of six aircraft in 1909, which is considered the first volume production of aircraft. I would say this is with the possible exception of the Wright Brothers. Let’s explore that a little.

On December 17, 1903, the Wright Brothers made the first four successful heavier than air flights in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. They immediately packed up and returned to Dayton Ohio for Christmas, as they had promised their family. In early 1904 they began looking for a place to continue their experiments in Dayton. They soon found a large field, “Huffman Prairie”, a 100-acre cow pasture. At first, they had numerous failures and accidents, often resulting in changes to their design. They also began working on plans to sell their aircraft and to obtain a patent. In October 1904, they were visited by Lt. Col. John Capper of the Royal Engineers, an official from His Majesty’s Government- their first potential customer.

By 1905, tests had resulted in a separation of the rudder and wing-warping controls and, after a particularly bad crash by Orville, they had completely redesigned the elevator- making it larger and heavier. These changes made the aircraft much more stable and they began making longer flights as well as controlled 180 and 360 degree turns. In October 1905, Wilbur made a flight of 39 minutes duration which travelled over 24 miles. The flight was made in 30 circles over Huffman Prairie, and ended when the fuel ran out. It was only then that the brothers considered their invention truly successful.

As is well known, the Wright Brothers were very concerned about getting a patent for their invention (specifically the control system). They were especially concerned about press coverage of their flights and so, at the end of 1905, they stopped flight testing and did not fly again until 1907.

This period of time was very eventful for the Wrights. They were involved with numerous negotiations with British, French, U.S., and even German governments. The negotiations took many forms and started and stopped many times. The main hang-up was always that the Wright brothers refused to demonstrate their plane in flight until they had a signed contract.

In 1907, Wilbur travelled to France, where they had received the most interest. During this time, Orville had continued working on building a series of five planes- which they wanted to have prepared for the hoped-for contract. They first flew again in early 1908- back in Kitty Hawk with one of these planes. Then Wilbur flew one in Europe and Orville demonstrated one in Washington. The Short brothers used more production line techniques in 1909, while Orville hand-built his five aircraft individually, but I expect Orville considered these aircraft “production” planes. Like so many things about the Wright brothers, this question is open to interpretation and there are many parts of the story that are not known (such as what happened to several of the five planes)- which makes their history so interesting.

MUSEUM WEBSITE

https://www.nmrn.org.uk/visit-us/fleet-air-arm-museum

UP NEXT

Part 2 of the Fleet Air Arm Museum

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

My friend Doug Campbell submitted this photo and the accompanying description. Doug and I are working on a book, loosely based on these blogs, which we plan to publish later in the summer. Watch for details!

Maxwell Air Force Base, in Montgomery, AL has a proud tradition in the history of aviation, dating all the way back to a Wright Brothers flying school, which was built on the site in 1910. Maxwell is also the site of the headquarters of the Civil Air Patrol (CAP). Founded on 1 December 1941, the CAP was mobilized in WWII to use the nation’s civilian aviation resources for national defense service. In front of the headquarters is displayed this representative aircraft of the CAP.

Cessna 305A, aka O-1A and L-19A “Bird Dog” with the civilian registration number N6258 has been displayed in Civil Air Patrol colors at CAP National Headquarters, Maxwell AFB, since 1983. Photograph courtesy Mark Hilton.

This particular Cessna 305A, also known as an O-1A and L-19A “Bird Dog” was used extensively for Forward Air Controller service in Southeast Asia (unrelated to the CAP). Forward Air Controllers (FACs) played a significant part in the Vietnam War from the very start. The “Bird-Dog” now on display was made available to Civil Air Patrol from DOD excess sources and the type is a proven vehicle in the performance of the CAP emergency services mission.

Thanks Doug!

—————————————————————————————————————————————

PHOTO GALLERY

Click any photo to enlarge

Issue 46, Copyright©2024, Pilot House Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved. Except where noted, all photos by the author