Fleet Air Arm Museum, Part 2

Issue 47 A visit to the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton, England (Part 2) June 2024

----------------------------------------

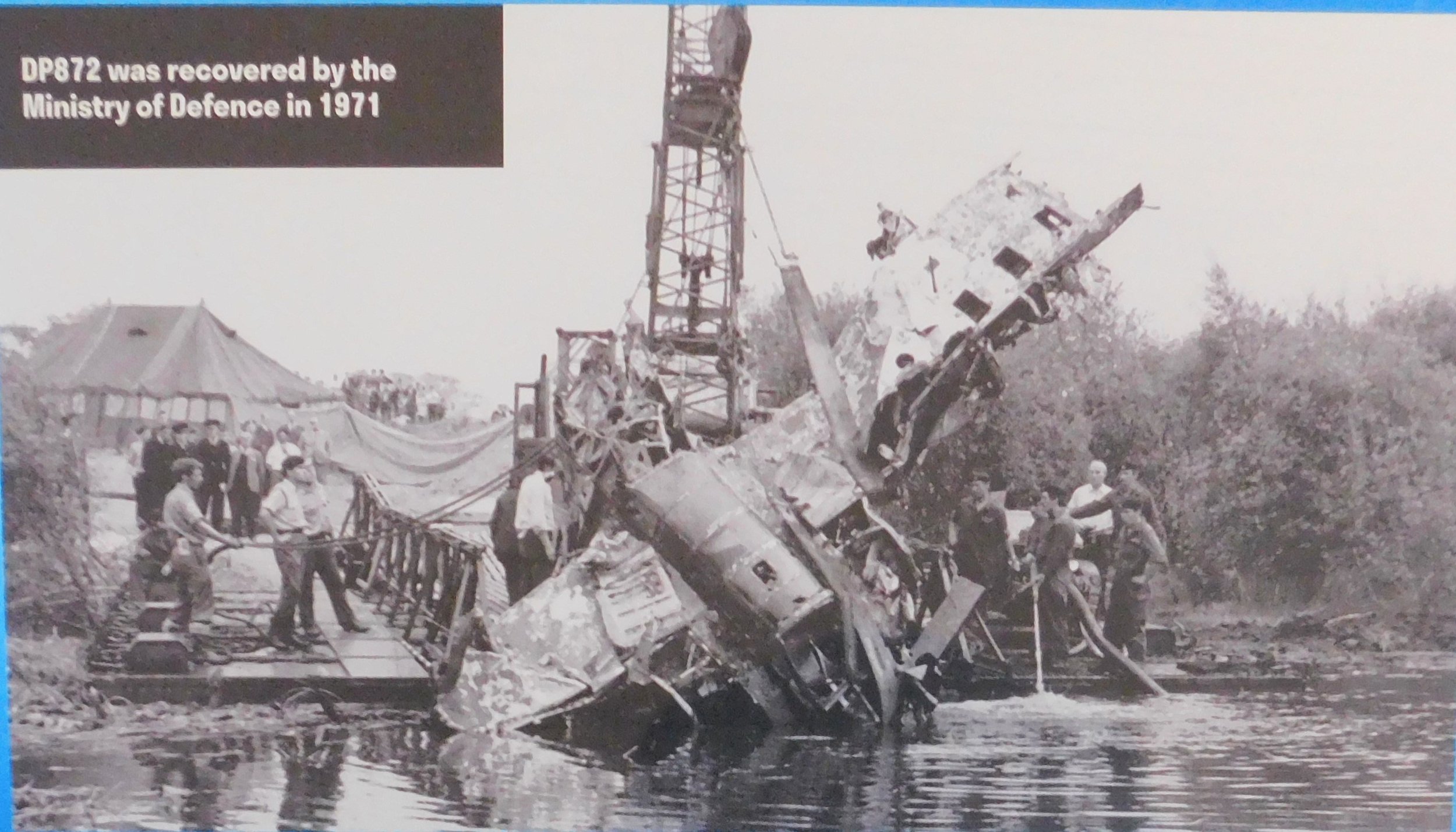

On 29 August 1944, A Fairey Barracuda dive bomber, DP 872, departed Royal Naval Air Station Maydown, in Northern Ireland, bound for RNAS East Haven, in Scotland. The plane went down shortly after takeoff and sank in Blackhead Moss, a peat bog. Rescue crews arrived quickly, but were unable to rescue the crew of three. In 1971, remains of the aircraft were recovered and now form the basis of a long-term restoration. The ongoing restoration, called “Barracuda Live: the Big Rebuild” is on display at the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton, in the west of England.

The entire restoration process is thoroughly documented on various placards around the restoration. More about the project later.

As discussed in the previous issue, the Fleet Air Arm Museum has been located on Royal Naval Air Station Yeovilton since 1964. The location for RNAS Yeovilton was identified in 1938 and the station opened in 1941. The station was originally home to 750 Naval Air Squadron and the Naval Air Fighter School. In addition, Westland Aircraft developed a repair facility at the site. Also based at Yeovilton was 827 Squadron which operated the Fairey Barracuda. Royal Naval Air Station Yeovilton is still an active base hosting the Maritime Wildcat Force, the Royal Navy Commando Helicopter Force, and the Army's Aviation Reconnaissance Force. The station operates over 100 aircraft. At the end of Hall 2, there is an observation room that lets visitors view military operations- such as this rainy weather start and lift off of several helicopters.

In the last issue, we covered Hall 1 & 2. We begin this issue with Hall number 3, titled “Aircraft Carrier Experience“

The first area you come to is a representation of a carrier flight deck. Although clearly much smaller in size than an actual carrier, it does give visitors a feel of being on a flight deck. One wall has a huge screen playing videos of naval events, with vast ocean views (now, if they could only make the deck roll!). The aircraft on the deck represent all eras of Royal Navy Aviation.

Like most World War I aircraft on display in museums, this Sopwith Pup is a replica. Introduced in 1916, the Pup was an immediate success in a variety of roles. With docile handling, it was immediately superior on the front lines. By 1917 however, Germany was introducing more powerful aircraft and the Pup was moved off the front lines to provide home defense, as well as being widely used as a trainer. Because of its docile handling, the type was also tested for onboard service with the Royal Navy. On 2 August 1917, Squadron Commander Edwin Harris Dunning made the first ever landing aboard a moving ship (Eugene Ely made the first ship landing in 1911, but that was on a ship that was docked). Dunning lost his life when the Sopwith went over the side of the ship on his third landing.

The Pup began formal operations on carriers in 1917. The first planes assigned to ships were fitted with skid undercarriages and a system of deck wires was used to "trap" the aircraft. Later versions reverted to the normal undercarriage. During WWI Pups were used as ship-based fighters on three carriers: HMS Campania, Furious, and Manxman. Other Pups were launched from platforms built on cruisers and battleships. A Pup flown from a platform on the cruiser HMS Yarmouth shot down the German Zeppelin L 23 off the Danish coast on 21 August 1917. The U.S. Navy also tested the Sopwith Pup for use as a carrier-borne fighter.

The Sopwith was officially named the “Scout” but early operators coined the nickname “Pup” because Sopwith was also manufacturing a larger two seat aircraft. The name soon became permanent. Powered by a Le Rhône 9-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine, 1796 Pups were built.

The Supermarine Attacker first flew in 1946 and was introduced into the Royal Navy in 1950. Powered by a Rolls-Royce Nene engine, the single seater was the first jet fighter to operate in the Fleet Air Arm. The Attacker had good flight characteristics and the forward cockpit location gave the pilot excellent visibility. The tail wheel design, however, made for difficult carrier landings. Like most early jet fighters, the Attacker had a short operational life due to rapid advances in technology, especially in swept wings and jet engine design. Retired from the active Navy in 1954 and the reserves in 1957, some aircraft continued to serve in the Pakastani Air Force into the early 1960s. This Attacker, WA 473, is the only known survivor.

In the 1960s, the Royal Navy needed a new fighter to replace the aging Sea Vixen. With costs of aircraft development soaring, the Fleet Air Arm (and the RAF) looked to acquire existing aircraft- such as the McDonnell Douglas Phantom II. The decision was made to acquire the Phantom II, which would be powered by Rolls-Royce Spey engines rather than the original General Electric J79. The reason for the engine change was two-fold. British carriers were smaller than U.S. carriers, and the increased thrust of the Rolls-Royce engine would aid in catapult shots. In addition, the change would allow a major portion of the Phantoms to be built in Britain. The aft fuselage had to be re-designed to accommodate the larger Spey engines, which resulted in even more local work. The Fleet Air Arm aircraft were developed from the F-4J model and were designated the F-4K (the RAF version, which was similar to the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) version was designated the F-4M).

Besides the more powerful engines, the FAA Phantoms had an extended nose strut to further assist in catapult launches, by increasing the angle of attack. This F-4, XV-586, is dramatically displayed on a catapult ready to launch.

Above the carrier deck there is a re-creation of the bridge as well as the Flying Control Position- “Flyco”, which is basically the ship’s tower (U.S. carriers call this area Primary Flight Control- “PriFly”).

There are several ways to reach the Flyco but the most interesting is to travel up in a re-creation of the ship’s elevator. This large elevator represents the elevator that takes planes from the hangar deck to the flight deck. As you travel up, you stop at several locations and a wall-sized video screen comes to life.

At each location, a ship’s crewmember gives you an overview of what goes on in that location. The elevator stops in the engine room, the crew quarters, and the hangar deck. The ‘ride’ is extremely well executed and is an experience not to be missed.

Although it represents a ride from the hangar deck to the flight deck, this elevator lets you off in the bridge area. From here you begin a trip through various sections of an aircraft carrier.

Starting on the bridge and Flyco, you get a nice overall view of the flight deck.

As you travel through the carrier display, each section has been taken from an actual carrier that was being dismantled. Although the display is a general representation of a Royal Navy Carrier, the HMS Ark Royal was mentioned often as the donor for a particular display area. There have been four ships named HMS Ark Royal that have served as aircraft carriers. In 1914 a freighter under construction was modified and completed as a seaplane carrier and named Ark Royal. Ark Royal (91) was built in 1937 as an aircraft carrier and was sunk by a U-boat in 1941. HMS Ark Royal (R09) was launched in 1950 and decommissioned in 1979. HMS Ark Royal (07) was launched in 1981 and decommissioned in 2011. Today the Royal Navy operates two aircraft carriers- HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales.

As you can see, each area gives you a real feel of being on a carrier. Passages connect specific areas where the daily operations are described by a life-sized video of a crew member.

Here we see the radar room, manned as it would be during at-sea operations.

Each passageway contains all the small details, from fire hoses to emergency fuel shut-offs, that give visitors a real feel of being on a carrier at sea.

Here a weather briefing is being conducted for a training mission. It is clearly an actual ready room and the information on the grease board gives a detailed overview of the mission.

Obviously a hub of activity, the Aircraft Control Room personnel organize aircraft on the flight deck and hangar deck, as well as logging the maintenance status of each aircraft.

Although difficult to photograph, the screens with ship’s staff describing the operations of the various areas are well-done and informative.

After following the route through all the various parts of the aircraft carrier, the final passageway takes you downstairs and into our final section- Hall 4.

This Hall contains a wide variety of aircraft, but clearly dominating the space is the British Aerospace Concorde.

This Concorde, 002, was the first British built Concorde and it was used exclusively as a test aircraft. It first flew from nearby Bristol Filton airport on 9 April 1969. There were two test aircraft (001 and 002), as well as 2 pre-production aircraft (101 & 102), and two development aircraft (201 & 202). The Concorde was built by a collaboration of Sud Aviation (later Aérospatiale) and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC). Of each test pair, one was British and one French. After seven years of testing of these six aircraft, 14 production aircraft were built and they went into passenger service in early 1976 (seven with British Airways and seven with Air France). Once the production Concordes went into regular service, the test programs were complete. On 4 March 1976, 002 made its final landing at RNAS Yeovilton to take its place in the Fleet Air Arm Museum. Of the 20 total aircraft built, one was scrapped and one crashed. The other 18 are all on display in various locations. The Fleet Air Arm Museum makes the point that, although not a Royal Navy aircraft, the Concorde was built, and flew test flights nearby, and much of the technology tested on Concorde 002 found its way into modern Naval aircraft. They really don’t need to justify the Concorde being in this museum-the other 17 Concordes on display are located in a variety of different, and sometimes unlikely, locations. There is one, for example, on the deck of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier Intrepid, berthed in the Hudson River. I have 15 landings on the Intrepid and I never saw a Concorde out there!

As I pointed out in the last issue, this museum has many aircraft open to visitors- an excellent feature. The Concorde is probably the most interesting of the open aircraft as you get to see all of the test equipment that was used on the plane, still in place.

My first stop inside, of course, was the cockpit. It is all there, just as it was on its final flight in 1976. It is interesting to see this very technically advanced aircraft with its original old-style gauges and flight displays.

The gauges and controls are pretty much the same as you would find on any airliner of the 1960s and 70s. The M shaped yoke or “Ram’s Horn” was common on British aircraft of the day and is still found on Hawker and Embraer aircraft.

Even the flight engineer’s panel (protected behind Plexiglas) is very similar to the panel on a 707 or DC-8. The main difference is that the engineer’s panel on the Concorde is in a much more compact space. The cross section of this fuselage is quite small.

Even with all of the test equipment in place, you can get a feel for the small diameter of the fuselage- the passenger cabin was just 103 inches wide. For comparison, the cabin of a 737 is 139.2 inches wide. To complete the comparison, of course, the Concorde flew at Mach 2 while the 737-200 (1976) flew at Mach .73.

The Concorde flew at altitudes of up to 60,000 feet, while maintaining a cabin altitude of around 6,000’; the issue of a loss of pressurization was a big concern during Concorde testing. One of the reasons that the Concorde had such small windows was to minimize the speed of pressurization loss in the event a window would blow out.

All of the test equipment used aboard Concorde 002 was basically analog- lots of wires and weight. The avionics circuits on the Concorde were hybrid circuits- a step towards todays digital circuitry. The flight control system was “fly-by-wire”, to save weight, but the system was analog.

If you are interested in more information about the Concorde, the pre-production Concorde 101 is on display at the Imperial War Museum in Duxford and they maintain a very informative website about the plane, including an interesting documentary video.

https://www.heritageconcorde.com/

Not all the research on supersonic flight was conducted by the test Concordes. In 1954, the Fairey Delta II made its first flight for delta wing research. It was the first aircraft to fly greater than 1,000 MPH in level flight.

The BAC 221- a converted Fairey Delta II.

Fairey Aircraft was bought by Westland in 1960 and the Delta II program was moved to Filton. It was decided to use the prototype Delta II, WG 774, as a test bed for Concorde. Major modifications were made, including lengthening the fuselage, raising the height of the landing gear, and fitting a completely new ogival wing, like the Concorde would have. The ogival wing shape allowed the Concorde to fly efficiently at high and low speeds without the use of any high lift devices such as flaps or slats. The wing allows a wide speed range simply by changing the angle of attack (the angle of the wing compared to the relative wind)- with slow speeds possible through a high angle of attack. This creates ‘vortex lift.’ To accommodate the high angle of attack for takeoff and landing, the Concorde had a droop nose (the modified Delta II also had a droop nose). For takeoff, the nose drooped 5 degrees, while the droop for landing was 12.5 degrees. The modified Delta II was re-named the BAC 221, and is on display next to the Concorde.

The Fleet Air Arm Museum has over 100 aircraft in is collection, with only about half of them on display at any given time. During my visit, the 50th anniversary of the Falklands War was featured, and we saw some of the participating helicopters from the Falklands in Part 1.

Hall 4 has some more of the display, including a presentation of a Harrier on a carrier deck ‘ski-jump’.

In 1978, the Royal Navy began testing the idea of launching the Sea Harrier from a curved ramp off the front of a carrier. The testing, which took place at RNAS Yeovilton, proved the concept and, in 1979, ramps were installed on all active British carriers. The Hawker Siddeley Sea Harrier FRS.1 / FA.2 (XZ493) is on display on a representation of a carrier ski jump. First flown at the end of 1980, XZ493 arrived at RNAS Yeovilton in early 1981 to become the first plane of the newly formed 801 NAS. The squadron flew onto HMS Invincible in April 1982, setting sail the next day for the Falklands War. Harriers were the only fixed wing fighters available to the British during the war and they provided all the types of combat air patrol (CAP) missions required during the conflict.

Fairey Barracuda Mk II of 814th Naval Air Squadron over HMS Venerable (R63) Public domain photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

At one end of Hall 4, there is a roped off work area that is in clear view of visitors. This is where the Barracuda, from the opening story, is being restored.

This project is creating a restored Barracuda out of the remains of the Irish bog crash, as well as from parts of a plane that crashed in the Solent and original parts recovered from other crashes. This long-term project is just one more way the museum illustrates not only the historic aircraft but the restoration and documenting of history. Here’s how the museum website describes this Barracuda project-

“ Not a single complete Barracuda aircraft exists in the world today. Their legend will live on with Barracuda Live: The Big Rebuild as the Barracuda DP872 is reconstructed in our new Arthur Kimberley Viewing Gallery. Come and be blown away by the incredible story of the Barracuda and Fleet Air Arm Museum’s 50-year journey to rebuild the aircraft. This remarkable project has been underway since the 1970s. Led by the Fleet Air Arm Museum, their ambitious mission is to reconstruct a complete (non-flying) Barracuda aircraft.

Piece by piece, a passionate team has been gathering parts from wreck sites, with permission from the Ministry of Defence, across the British Isles. Their unwavering commitment is driven by a desire to not just preserve the aircraft but also to honour the courageous individuals who built, flew, and maintained them. It's been eight decades since the Fairey Barracuda was last seen in its entirety but that is set to change as the Fleet Air Arm Museum unveils Barracuda Live: The Big Rebuild.”

All of the steps of the restoration process are on display and any time you visit you are likely to see work being conducted on the Barracuda. This is truly a unique museum display.

While writing about The Fleet Air Arm Museum, I have used many superlatives- and they are all well deserved. It is an outstanding aviation history museum.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Once again I would like to thank Conor O’Hanlon, Content and Communication Executive for the museum, who helped me with my research, as well as all the museum staff who were happy to answer questions during my visit.

A few other “thanks” that I should add to all of my blogs. My son Mark and his wife Taylor helped me do the initial design of the blog and website; my son Eric is always helpful with technical questions; my son AJ not only offers technical advice, but is very generous with offering rides to museums in his Baron; and my daughter-in-law Angela often has valuable input and suggestions. My brother Mike edits the blog each month with very valuable input. Above all, my wife Sheri provides support and encouragement and often accompanies me on museum visits. A huge thanks to everyone.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

To learn about museum hours and costs as well as books to read and other interesting odds and ends, keep reading! At the end you will find a photo gallery with more pictures of the museum.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

The Fleet Air Arm Museum is in Yeovilton in the West of England. It is convenient on any trip to the West or Southwest of England. It is 40 miles from Stonehenge, 30 miles from the historic town of Bath, and 50 miles from Bournemouth, on the south coast. For music fans, it is just 18 miles from Glastonbury.

Open 10am to 4.30pm, Wednesday to Sunday

Adult £22

Child (3-15) £16

Senior £21

There is a discount if tickets are purchased on line and there are also family discounts available.

MUSEUM WEBSITE

https://www.nmrn.org.uk/visit-us/fleet-air-arm-museum

SUGGESTED READING

“As a dreamer of dreams and a travelin' man I have chalked up many a mile Read dozens of books about heroes and crooks And I learned much from both of their styles” Jimmy Buffett (1946-2023)

Something a little different this month. I received a note from reader Bruce Barth who is a writer and historian. Among other things, Bruce consulted with Jimmy Buffet while Jimmy was writing “Where is Joe Merchant?”.

Here is a review of this quirky book from “Bookreads”-

“Where is Joe Merchant? That's what his sister, Trevor Kane, the hemorrhoid-ointment heiress, wants to know. For Desdemona, Merchant is the missing link in her ongoing communications with space aliens. Tabloid journalist Rudy Breno only cares that Merchant gets bigger headlines than Elvis. And for renegade seaplane pilot Frank Bama, the mystery of the presumed-dead-but-often-sighted rock star is turning his life upside down. In his debut novel, Jimmy Buffett cooks up an irresistible gumbo of dreamers, wackos, pirates, and sharks, as he leads Trevor and Frank on a wild chase through the Caribbean Islands to a place where anything can happen . . . and everything does.”

Jimmy’s humor and fantasy writing style may not be for everyone, but there is plenty of seaplane flying.

The reason Bruce sent the note is that he has his collection of Martin seaplane research for sale.

I don’t include any advertising in this blog, but this collection of research is historically important and deserves to be preserved. If anyone has any interest or ideas for Bruce you can contact him directly.

WRIGHT BROTHERS STORIES

Many historians who write about the Wright Brothers conclude that neither Orville nor Wilbur would have invented the airplane on their own. I very much agree with that conclusion, each brother having different skills, interests, and goals. These interests often conflicted, but ultimately, their collaboration was what led to their success.

Wilbur was four years older and the one who first developed a serious interest in aviation. In many ways, he was the driving force in their achievements. Given that the invention of flight was a result of deep collaboration between the two brothers, an event in 1885 almost ended the partnership before it started.

Wilbur was an excellent student in high school, and a top athlete. He was on the football team and the fastest runner in the school and he was planning on attending Yale. Sometime during his senior year (details of this event and its aftermath are one of the haziest areas of the Wright’s history), Wilbur was playing hockey on a frozen lake when he was hit in the mouth with a hockey stick. Besides losing a lot of teeth, he did not seem badly hurt. In subsequent weeks and months, however, Wilbur started having serious heart and internal issues. As was common at the time, medicine did not have the equipment or knowledge to treat his problems. Wilbur withdrew from the public and gave up on Yale- or attending any college. This withdrawal lasted for three years and it is not hard to theorize that if it had continued, Wilbur would not have been able to return to a normal life, let alone participate in the great physical and mental effort that the brothers went through to design, build, and fly their invention. It is, in fact, probably true that Wilbur almost died from the incident itself (it is not clear if the hit in the mouth was intentional or an accident but the player who hit him, a local bully, was later executed for committing several murders).

Although suffering physically and emotionally, Wilbur did not just lay idle. His mother, Susan, had been ill for some time (she would pass away in 1889) and Wilbur spent the three years nursing her and attending to her needs. The family house had a large library and Wilbur spent much of his spare time reading. After three years, he was feeling strong enough to return to society and his first venture out in public was to make a presentation in support of his father, who was having legal problems with his church. Over the next decade, Wilbur continued to read and learn (although he never did graduate from high school) and regain his strength and public confidence.

The story from 1899 on is well known and Wilbur is remembered as a brave adventurer who, along with Orville, conquered flight. The story of his near fatal accident and long and difficult recovery is not as well known.

Wilbur Wright died of Typhoid Fever in 1912, at the age of 45, most likely partially weakened by his earlier injuries.

UP NEXT

A tour of the newly opened Sullenberger Aviation Museum in Charlotte NC.

MUSEUMS ARE WHERE YOU FIND THEM

This segment is dedicated to finding interesting aviation artifacts that are in public view- but not in an aviation museum. If you see one send a photo!

This topic doesn’t exactly fit the category but I wanted to write about this display before it is changed.

I recently installed this display cabinet in the main terminal at Dare County Airport to display items connected to aviation on the Outer Banks.

On the Outer Banks, the Wright Brothers, of course, have a museum, and the Dare County Airport Museum covers WWII as well as the life of aviation pioneer, Dave Driskill (I wrote about the main museum in Issue 36 and Issue 44). This rotating display is designed to showcase everything else aviation connected to OBX. Several years ago, I became aware that the Town of Kitty Hawk had been given many artifacts from the de-commissioned aircraft carrier, USS Kitty Hawk. Unfortunately, only a few of the items were on public display. The rest were stored in a storage building. It seemed like a great opportunity to make these items the first display in the new cabinet. All the items here (except the aircraft models) are on loan from the Town of Kitty Hawk. Some of the photos are by Kitty Hawk police detective Jason Rigler.

Photo Courtesy of Jason Rigler

The Kitty Hawk was originally launched as an attack carrier, CVA-63. In 1973, she was modified to be a multi-purpose carrier, CV-63. Many of the modification involved accommodating Anti-submarine warfare aircraft and systems. In 1977, the Kitty Hawk was again modified to carry F-14 and S-3 aircraft. In this undated photo from later in the Kitty Hawk’s career, S-3s can be seen as well as F-18s. There is also an E-2 and several A-6 Intruders.

Photo Courtesy of Jason Rigler

Launched in 1960, the USS Kitty Hawk was decommissioned in 2009, after 48 years of service.

Serving virtually all her active years on the West Coast, The Kitty Hawk saw lots of action during the Vietnam War.

Photo Courtesy of Jason Rigler

Bob Hope entertaining on the Kitty Hawk in the Gulf of Tonkin.

An excellent example of Boatswain’s Mate art, this mat sat outside the Captain’s cabin on The Kitty Hawk.

Photo Courtesy of Jason Rigler

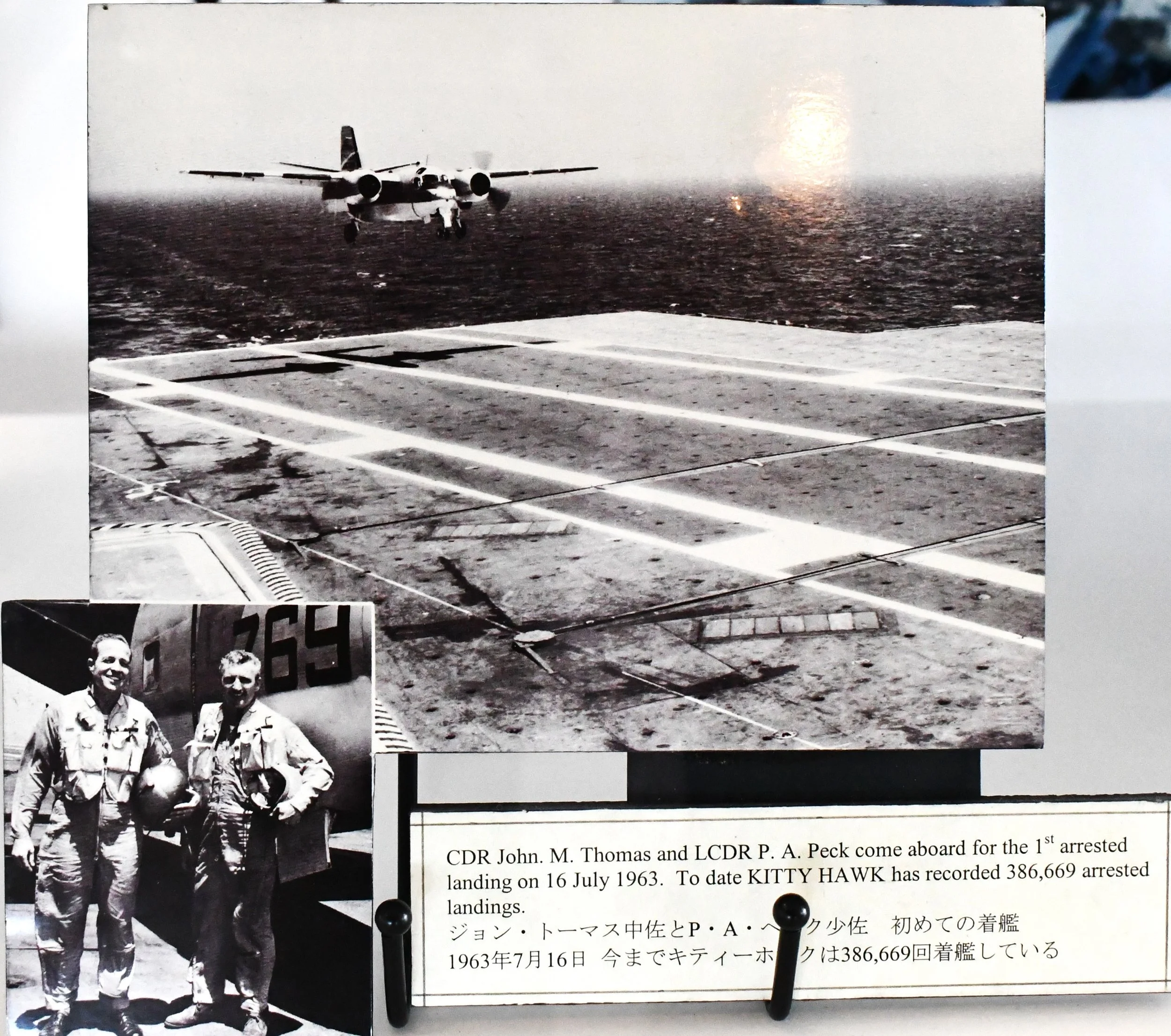

Although I never landed on the Kitty Hawk, I do have landings on two of her sister ships- the JFK and the America. When preparing the display, I found a connection to the Kitty Hawk through this photo showing a C-1, the plane I have most of my carrier landings in, making the very first landing on the Kitty Hawk.

Several more items from the Kitty Hawk are displayed on a nearby wall, including the Secretary of the Navy Ensign, which was flown while Navy Secretary John Lehman was on board. Note- I was researching this flag and found that this flag, with a red background, is actually for the Undersecretary of the Navy. The same flag, with a blue background was for the Secretary. The flag and accompanying placard came directly from the USS Kitty Hawk, so I am not sure of the reason for the discrepancy. I spoke with a friend, retired Admiral JT Tynch, who was a carrier skipper, and he confirmed the colors. If anyone has any thoughts on the matter, let me know.

The Kitty Hawk was the last conventional aircraft carrier in the Navy Fleet. Several groups spent over 10 years lobbying and fund raising to preserve her as a museum. Unfortunately, they were unsuccessful, and the Kitty Hawk was towed from Washington to Texas in 2022, and the scrapping was completed this year.

Many thanks to Breynn Bailey who helped me curate this display.

PHOTO GALLERY

Click on any photo to enlarge

Issue 47, Copyright©2024, Pilot House Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved. Except where noted, all photos by the author